Bactrian Horse, Tang Dynasty, China, 700-800: The develop...

-

Bactrian Horse, Tang Dynasty, China, 700-800: The development of the “Silk Roads” – terrestrial links between Asia and Europe – led to a centuries-long trading of ideas and artistic techniques across continents. One of the earliest beneficiaries of this was the Chinese empire of the Tang dynasty (618-907), which imported many exotic products, including glass, ivory and pearl, from Central Asia. The influence of this can be seen in the funerary figurines – or mingqi – which accompanied the dead when they were buried. -

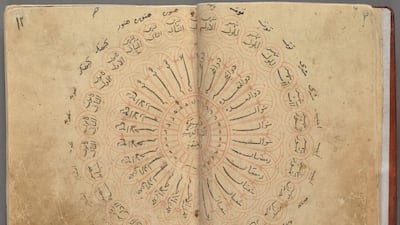

Treatise on calendars, a study of astrological calculations, Iraq, around 1200: Most likely produced for one of the sons of the last Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad, Al-Musta’sim (1213-1258), this is a series of astrological calculations advising on the best moment to undertake a variety of actions, including when to travel by land or sea, when to wage war and even when to take a bath. The complexity of the content is astonishing, while the faded red and black ink marking the yellowing pages imbues this stunning object with a tangible sense of age. -

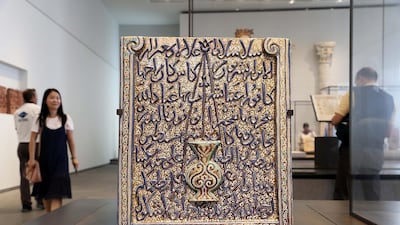

Fragment of a plaque in the form of a mihrab, Central Asia, 1250-1350: There is very little historical information accompanying this large broken slab of lusterware depicting a mihrab (the niche in the wall of a mosque indicating the qibla or direction of Mecca) but it really doesn’t matter. Instead, you should just bathe in the deep blues and turquoises, which shimmer beneath a metallic glaze, and marvel at the elaborate swirls decorating the central lamp (a reference to the Quranic surah about light). Photo: Pawan Singh / The National -

Photo: It might seem odd to suggest that a painting by Yves Klein, one of the great European post-war artists, is a “hidden treasure”. But in a room where there are works by, among many others, Henri Matisse, Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol, it would be easy to miss this gorgeous, smudgy wonder. Untitled Anthropometry is an imprint of the bodies of the artist and his wife painted in International Klein Blue, a pigment created and trademarked by Klein in 1956. Photo: Pawan Singh / The National -

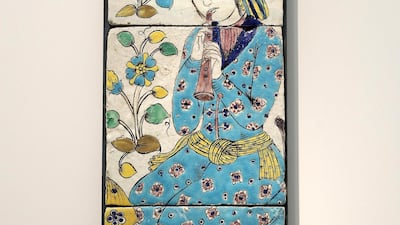

Panel with a flute player, Isfahan or Qazvin, Iran (1680-1730): Perhaps it’s the bowl of pomegranates in the foreground or the exotic yellow and blue plants dancing down the left-hand side but this three-tile ceramic interior decoration has a wonderful feeling of freshness, exuberance and youthful joy. Scenes such as these were widely used in Iran during the 17th century for the decoration of palaces in Isfahan. Pawan Singh / The National -

Assemblage: Female Nude Sitting in a Pot, Auguste Rodin (1900): Rodin, the guide tells us, “believed that the primary characteristic of classical art was its candour, simplicity and purity with regard to nature, qualities that he himself sought in his own works”. I am particularly fond of Assemblage: Female Nude Sitting in a Pot (1900). It is a messy, almost clumsy, sculpture. The pot is smeared with plaster and you can see the joins on the woman’s form. And yet, Rodin has still managed to convey so much energy and movement in a few simple shapes. -

Chinese coins, 600-200 BCE: The history of these small objects – whose influence on humanity cannot be overstated – is told in a little room in the corner of Gallery 2. It is easy enough to miss it but seek it out, for there are treasures here from across the globe including Greece, India, Rome, Turkey and the UAE. This room also has one of the best interactive experiences in the museum, allowing visitors to see magnified images of each individual coin. Photo: Pawan Singh / The National -

Sword of Boabdil, the last emir of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada, Toledo, Spain (1475-1525): Boabdil swords are named after Muhammad XII of Granada, the last Nasrid sovereign of Granada in Iberia (Boabdil is the Spanish name), who was defeated by Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon in 1492. The blade, whose solid silver handle is embedded with beautiful coloured cloisonné enamel and gold filigree, is strikingly long, a violent reminder that these artefacts once had real-world purpose. But the real star is the leather scabbard, which is embroidered with intricate silver thread and bears the Nasrid motto, “There is no victor but God”. Photo: Pawan Singh / The National -

Reliquary casket with the Three Magi, Limoges, France (c.1200): This intricately crafted reliquary casket from the 13th century, which would have housed fragments of bone or clothing belonging to a Christian saint, sits alongside an urn from Italy (600 BCE) and a portable temple from Fiji (before 1900). Christian pilgrims would travel many miles to see a reliquary casket such as this one, which depicts scenes from the New Testament story of the Three Kings. The vibrant blue and gold casket is designed using a technique called champlevé, which involves carving shapes into a metal surface, filling them with coloured enamel or powdered glass and then heating the metal until the substances fuse. Photo: Pawan Singh / The National -

ABU DHABI , UNITED ARAB EMIRATES, September 16 – 2018 :- Untitled Anthropometry (ANT 110), Yves Klein, France, Paris, 1960 on display at the Louvre museum in Abu Dhabi. ( Pawan Singh / The National ) For Arts and Culture. Story by Rupert Hawksley

Most popular today