Nine years after the death of a Tunisian street vendor sparked the Arab uprisings, a new survey has suggested a major catalyst of the protests has yet to be addressed.

Corruption is still rife across much of the Middle East, and continues to grow, according to the latest report from Transparency International.

Its Global Corruption Barometer asked residents of six countries - Sudan, Lebanon, Jordan, Morocco, Palestinian territories and Tunisia - about their experiences.

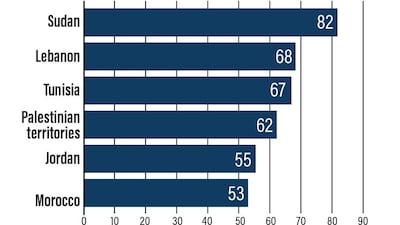

All reported widespread corruption, with more than six out of 10 surveyed believing the issue had increased over the past 12 months.

Sudan was found to be the worst offender, with 82 per cent of people believing corruption had risen, followed by Lebanon with 68 per cent.

Morocco and Jordan were the least affected, but even here, more than half said they believed corruption was still on the rise.

In the Palestinian territories, the figure was 62 per cent and in Tunisia, the birthplace of the Arab uprising, it was 67 per cent.

Transparency International was founded in 1993 and the international NGO, based in Berlin, Germany, seeks to combat global corruption.

Its latest annual report released on Wednesday found that barely one in 12 of the 6,600 people it surveyed said the issue was improving.

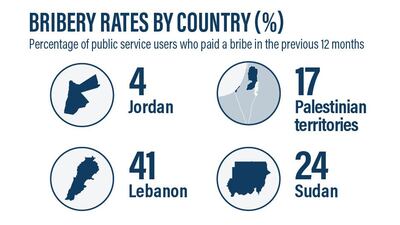

To get access to essential public services, such as health and education, one in five said they had been forced to pay a bribe to a public official.

Research showed this translated to around 11 million people across the six countries.

For Jordan, Lebanon and the Palestine territories, personal connections - or wasta - was deemed essential to ensure co-operation from officials, the survey found.

And for the first time, researchers also asked about instances where sexual favours were demanded by corrupt officials to access services.

One in five said they had experienced or witnessed “sextortion”, the survey found, although the real picture may be worse given many incidents go unreported.

The new survey comes amid a wave of street protests over corruption and unemployment in Lebanon and Iraq.

This week, a senior UN official warned that demonstrations across the world were the result of growing inequality.

"Those who hold the power … need to recognise that unless they can respond to the particular sense of grief that people feel, their legitimacy will be challenged" said Achim Steiner, administrator of the United Nations Development Programme.

“Corruption disproportionately affects the most vulnerable people, depriving them of free and equal access to public services,” said Delia Ferreira Rubio, chair of Transparency International.

“People taking to the streets to speak out against corruption is a sign that regular channels for demanding accountability and transparency are inadequate.”

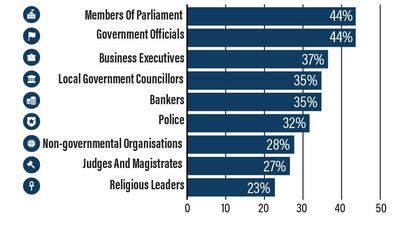

By institution, elected members of parliament were felt to be the most corrupt, followed by government officials, according to the research.

By contrast, religious leaders were seen to be the most honest by more than three quarters of the survey.

Of those who had been in contact with the police in the past year, nearly a quarter had paid a bribe, rising to nearly one in four in Lebanon, but only two per cent in Jordan.

The study also found that more than 80 per cent of Lebanese had little trust in their government. “In Lebanon, the dynamic between money and power is a common challenge to curbing corruption, particularly during elections,” Transparency International said.

It found that in the 2018 elections, offers of jobs, scholarships and medical and other services were widely used to buy votes.

Almost half of Lebanese voters were offered a bribe to secure their support, while around a quarter reported being threatened if they did not do so.

“Unfortunately, the Supervisory Commission for Elections, which is the government body in charge of monitoring elections and promoting electoral integrity, has limited financial and human resources to do its job, including curbing vote-buying,” the anti-corruption group reported.

The one positive sign is that exactly half of those surveyed felt ordinary people could still make a difference.

This optimism was greatest in Tunisia and Sudan, where 59 and 54 per cent respectively agreed individuals acting collectively could make a stand.

This view was least felt in Lebanon, where just under one in three felt their voice would be heard.