Last week, a Tunisian smuggler named Kamel Bouazi guided his pickup into a walled compound here to collect 100 plastic jerry-cans of contraband Algerian fuel.

Six months ago, Mr Bouazi would have sold the fuel for Tunisian consumption. "But now it's going to Libya," he said.

War in Libya has paralysed fuel production there, leaving both rebel and government forces dependent on fuel from Algeria, said John Hamilton, a Libya expert at Cross-Border Information, a British risk analysis firm.

That makes Algerian fuel and the men who traffic it decisive in the battle for Libya, increasingly a war of attrition as rebels try to strangle the regime of Col Muammar Qaddafi.

"It won't be won militarily," Mr Hamilton said. "It will be won by provoking the internal collapse of the regime by choking off its resources. They've got to cut off the fuel."

Last weekend, rebels entered the coastal city of Zawiya, blocking Col Qaddafi's main lifeline to Tunisia via a coast motorway. Yesterday rebel forces were fighting for control of a Zawiya oil refinery that is Tripoli's sole remaining source of power.

Col Qaddafi's fuel stocks may run out soon, while rebel forces badly need fuel to continue their struggle, Mr Hamilton said. "They have to maintain their advance, hold territory and keep their supply lines intact."

That is where men such as Mr Bouazi come in, sneaking fuel from Algeria to avoid customs duties and selling it increasingly to middlemen who sell in turn to Libyan buyers.

Much of the fuel trafficking is centred on the Tunisian city of Kasserine, where its strategic position near the Algerian frontier made it a battleground of the Second World War.

The city is an expanse of rundown concrete buildings in a broad valley, neglected by the regime of president Zine el Abidine Ben Ali and the scene of deadly clashes in the January revolution that overthrew him.

Kasserine's population has swelled in recent years to 282,000, while unemployment has skyrocketed to about 40 per cent, said mayor Maher Bouazzi, who is not related to Kamel Bouazi. "If you stop smuggling, you cut off the oxygen from this city."

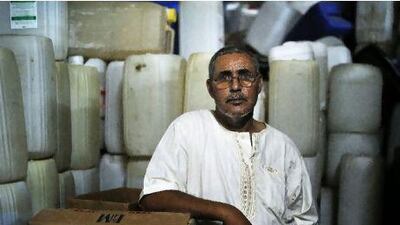

Kamel Bouazi began smuggling six years ago with his brother, Mabrouk. Last week he was at the border village of Bouderies once again to collect fuel from the compound of Redhwan, a burly Tunisian middleman who declined to give his surname.

The afternoon sun was beating down and Mr Bouazi stripped off his jean jacket. One by one, he and one of Redhwan's three sons heaved jerry-cans into Mr Bouazi's pickup.

"My kids are all going to school," Redhwan said, watching from the shade of the house. "They're studying. One day they won't be doing this work."

When the pickup was loaded, Mr Bouazi took a wad of cash from his pocket and peeled off 2,800 Tunisian dinars (Dh752,566). Then he washed his hands at a tap in the wall and drove away.

Back in Kasserine, Mr Bouazi went to see Ali Bouallegui, a successful middleman who got his start in 1985 by bringing electronic goods by donkey over mountain tracks.

In 1992, Mr Bouallegui began trading Algerian fuel, and lives today in a luxurious house above the garage that he uses as a depot.

"In the past, security was tight and only people connected to the family had permission to traffic," he said, referring to the ruling clan of Mr Ben Ali. "I didn't have permission."

That has changed radically since January's revolution, as security forces have receded while war in Libya has created demand there for Algerian fuel.

"The Tunisian market isn't very active now since the Algerians have raised prices," Mr Bouallegui said. "What is active is the Libyan market. Tunisians pay 29 dinars (Dh77) for a jerry-can of petrol; Libyans pay 50 (Dh132)."

Both Algeria and Tunisia say that they are trying to prevent fuel from reaching Libya following United Nations sanctions that ban fuel sales to entities linked to Col Qaddafi's regime, and have not authorised official fuel sales to the country.

While Tunisian authorities have pledged to increase security checks near the Libyan border, laxity prevails around Kasserine, according to smugglers and Mr Bouazzi, the mayor.

At some border villages such as Bouderies, Tunisian authorities are absent. At the village of Oum Ali, cars loaded with fuel cans and other goods roll unhindered past a Tunisian border post.

"I'd do other work if I could," said Faouzi Nabiha, 31, a Tunisian smuggler buying fuel at Oum Ali last week from his Algerian trading partner, Abdelhafid, 31. "I own 20 hectares near here, but there's no water to farm them."

Like Mr Nabiha and the Bouazi brothers, Mr Bouallegui similarly considers himself a prisoner of circumstance.

"I couldn't even dream of other work because there wasn't any," he said, drinking coffee at his house one evening last week. Beside him sat Wafa, 21, his daughter, who studies anesthesiology at a private university in the coastal city of Souss.

"My father pays 6,000 dinars a year for my education," she said. "I have a responsibility to achieve my dream, to become a doctor, which is also the dream of my family."

Meanwhile, conflict in Libya has added a geopolitical dimension to Mr Bouallegui's activities. He sells to Libyan fuel traders while taking a neutral stance on Libya's war.

"Ultimately some of the fuel goes to Qaddafi's militias, and some goes to the rebels," he said.

That issue may become moot if rebel advances definitively sever Col Qaddafi's access to Tunisia. For his part, Mr Bouallegui is focused on the daily realities of Kasserine.

jthorne@thenational.ae

-