LAHORE // Even now, the men at the steel mill where Mubeen Rajhu worked laugh at how easy it was to make him lose his temper.

Some people had seen his sister, Tasleem, in their Lahore slum with a Christian man. She was 18, a good Muslim girl. This couldn’t be allowed.

Ali Raza, who also worked at the mill, can barely contain a smile as he talks about the hours spent taunting Rajhu about his sister. It went on for months.

“He used to tell us, ‘If you don’t stop, I will kill myself. Stop!”’ Raza says.

“The guys here told him. ‘It would be better to kill your sister,”’ Raza says.

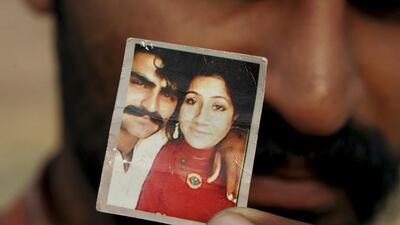

Rajhu told them he had bought a pistol, and one day in August he stopped coming to work. He discovered that his sister had defied the family and married the Christian. For six days he seethed with rage. On the seventh day, August 14, he retrieved the pistol from its hiding place and put a bullet in his sister’s head.

For generations now in Pakistan, they have called it “honour” killing, carried out in the name of a family’s reputation. The killers routinely invoke Islam, but rarely can they cite anything other than their belief that Islam doesn’t allow the mixing of sexes. Even Pakistan’s hard-line Islamic Ideology Council says the practice defies Islamic tenets. None of that matters away from the cosmopolitan city centres. In the slums and far-off villages, religion is inextricably tied to culture and tradition.

Even an upbringing in the West offers no protection from the brutality of tradition. Samia Shahid, grew up in Bradford, northern England and had lived in Dubai for two years before she was strangled to death in July while visiting relatives in northern Punjab. Her father and her cousin — the man she was given to in an arranged marriage — are now accused of her murder. Her crime? Leaving her husband to marry a man of her own choice.

In June, 22-year-old Muqadas Tofeeq’s throat was slit by her mother and brother. Muqadas, who lived in Butrawala, Punjab,was pregnant with her second child. Her crime too was marrying against her family’s wishes.

Last year, there were 1,184 victims of so-called honour killings, which works out at three a day, according to the independent Human Rights Commission of Pakistan. Only 88 of them were men. In 2014, the number was 1,005 women, including 82 children, up from 869 women killed a year earlier. In any year the true figure is likely to be higher because many such crimes go unreported.

Outrage at the practice is growing as Pakistani news channels report cases of girls who are shot, strangled or burned alive, most often by a brother or a parent. The country’s conservative prime minister Nawaz Sharif has promised to introduce legislation that will remove a legal loophole that allows the family of a murder victim to effectively pardon the murderer. The loophole is often invoked in honour killings to prevent any prosecution.

“You will die awaiting justice from a court,” said Mukhtar Mai, who was gang raped and paraded naked through her village as punishment for a perceived insult to the honour of a rival family by her brother.

“Girls are coming forward ... but the issue is that no one is listening to them,” she said. “Every time a woman tries to stand up to the system, the man-made system pushes her down hard.”

But many activists say it is the mindset of the boy who could bring himself to kill his sister, or the parent who could kill a daughter, that has to be understood, and changed.

Rajhu, who thinks he is 24 but isn’t sure, says he loved his sister, a quiet young woman who had never before rebelled against her family. He gave her a chance, he says; he demanded that she swear on Islam’s holy book, the Quran, that she would never marry the man. Frightened, she swore she wouldn’t.

“I told her I would have no face to show at the mill, to show to my neighbours, so don’t do it. Don’t do it. But she wouldn’t listen,” he says. Occasionally, his voice wavers and he seems remorseful.

Then his voice hardens. “I could not let it go. It was all I could think about. I had to kill her,” he says. “There was no choice.”

Tasleem was sitting with her mother and her sister on the cracked concrete floor of their family kitchen. “There was no yelling, no shouting,” says Rajhu. “I just shot her dead.” He has been held in shackles at police headquarters in Lahore for more than a month now.

His sister’s blood still stains the rough wall in the kitchen. Their father, Mohammed Naseer Rajhu, is also furious — with his daughter. He regrets only two consequences of his son’s actions — the young man is in jail and no longer earning nearly $200 a month, and his family, spread throughout Pakistan, will soon learn of Tasleem’s indiscretions.

“My family is destroyed,” says Mr Rajhu, his voice rising. “Everything is destroyed only because of this shameful girl. Even after death I am destroyed because of her.” Though he does not explicitly say he forgives his son, it is clear Mr Rajhu thinks the young man had every right to kill his sister. Making use of the legal loophole which activists are fighting, he has already begun the legal groundwork which will permit him to forgive the murderer — his son.

And when the police come to move the younger Rajhu to Lahore’s Kot Lakput prison, where he will go on trial, his father is at his side.

* Associated Press