Crude shot hundreds of feet into the air in Iraq in 1927 in a display that foretold of unimaginable wealth in the region. Now a Arabic translation of an oil explorer's work tells of the many people who started the business in black gold.

For thousands of years the “eternal” flames of Baba Gurgur burnt on near the city of Kirkuk in northern Iraq, inspiring legends, hope and simple warmth.

Women who believed them to have magical properties approached to ask that they bear a baby boy rather than a girl, while shepherds sought heat for their flocks in the cold winter.

The name translates from Kurdish into “Father of Eternal Fire”. It emanates rumbling from far beneath the earth’s surface because of gases that eventually inspired a team to start digging for one of the world’s most precious resources.

Oil was struck at 3am on October 15, 1927, by the Turkish Petroleum Company, the forerunner of the Iraq Petroleum Company. From then, Baba Gurgur became known as the world’s largest oilfield.

“Like an eruption from hell, first with a rumble, then with a deafening roar, oil burst out of the ground and rose above the derrick, raining down black crude and rocks on the surrounding wadi and filling nearby hollows with poisonous gas,” wrote Michael Quentin Morton in his book, In the Heart of the Desert: the Story of an Exploration Geologist and the Search for Oil in the Middle East.

Baba Gurgur was dethroned when the larger Ghawar field was found in Saudi Arabia in 1948.

Morton’s book focuses on his father Mike, who as an exploration geologist traversed the more remote parts of the Middle East between 1945 and 1984.

The book covers events in the UAE, Palestine, Iraq, Qatar, Oman and Yemen, which shaped the world in ways that continue to this day.

The book, which was published in 2006, has been translated into Arabic by the National Archives and was launched at the Abu Dhabi International Bookfair last month. The translation is timely.

“For us to know our future, we must know our past,” says Dr Abdulla El Reyes, director general of the National Archives. “The National Archives translated this book for its great importance as a reference. It is a critical history book, carefully documenting the story of oil and pre-oil era, showcasing the social, geological and political aspects and how it impacted the UAE and the Gulf region as a whole.”

With rare photos, maps and even caricatures, its 425 pages are a true journey back into time.

“It is a book that should be read by all who want to know about our past,” Dr Al Reyes says.

Morton grew up in Qatar, Bahrain and Abu Dhabi in the 1950s and 1960s and, after qualifying as a barrister, spent more than 30 years in a legal career.

He has written six books, of which four have been translated into Arabic by the National Archives. These include Black Gold and Frankincense (2010), a book of photographs taken mainly by his father and his colleagues during their exploration of southern Arabia between 1947 and 1971.

An account of the discovery and development of offshore oil in the UAE entitled The Petroleum Gulf, and Keepers of the Golden Shore: A History of the United Arab Emirates, is also being translated by The National Archives.

“In the Heart of the Desert is a biography of my father, who was a field geologist in the Middle East at a time when many parts of the region were relatively unexplored,” says Morton, 62. He lives in Kent, in the UK, but regularly travels to Abu Dhabi.

“By translating this book into Arabic, it will allow Arab readers to access an important part of their history, the search for and discovery of oil.

“I started writing after my father passed away in 2003. I discovered that the story of oil exploration was well worth telling because it provided a different perspective about the region.

“Most western accounts of the period were by British diplomats or military men and there was little about the early oil explorers.”

Emiratis will find the book significant because it explores the foundations of the UAE’s prosperity.

“I also hope they will learn that the discovery of oil was not the work of one individual but of many people from different backgrounds and cultures working together with a common purpose,” Morton says.

“My book enabled me to preserve the many stories my father told me when I was young, and I hope it will demonstrate the importance of oral history.”

The book offers rare drawings, including cartoonesque sketches by Morton Sr, and maps such as one from 1945 with Palestine written across lands that are now occupied by Israel.

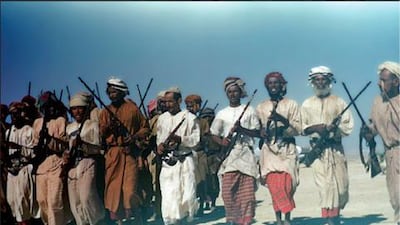

There are black and white photos of tribes removing worms from the nose of a camel, or holding a dhub lizard – a delicacy of the desert.

“While it is not always possible to draw exact lessons from history, I think the way that Emiratis recovered from the loss of the pearl trade and adapted to the massive changes from oil demonstrates that they are a resilient and resourceful people,” Morton says.

“I doubt that it is possible to go back to the way it was before the oil arrived, however retaining the traditional ways is an important part of the national identity.”

rghazal@thenational.ae