Prospective domestic workers are being offered practical advice from a new study of Ethiopian maids who have worked in the Gulf before.

The study, published last month in the journal Globalisation and Health, drew from individual and focus-group interviews with 35 women from Ethiopia's Amhara region, as well as their family members, local government authorities, teachers and community leaders. The 12 women who did in-depth interviews had worked in the UAE, Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

The research asks returnees what they wished they had known prior to their migration and for advice to make migration as safe as possible for prospective migrants.

“We have been trying to introduced the concept of safe migration rather than legal migration because, in fact, one of the things that comes out very strongly is that there is a real blur between what is legal or illegal,” said Joanna Busza, the lead researcher.

An estimated 170,000 to 180,000 Ethiopian women leave to work overseas every year and about 60 to 70 per cent of migrants to the Middle East are irregular migrants. The study found that potential migrants were determined to work abroad, despite Ethiopian government awareness campaigns warning of the potential for abuse and human trafficking in some cases.

RELATED: Should maids be allowed a mobile? Study says yes but some employers say no

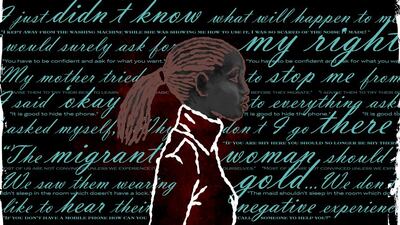

Many said they knew nothing of the Gulf before they left. Others had prepared for departure by seeking out information from returnee migrants, family members and neighbours.

Returnees said that although they trusted the campaign information, it did not dissuade them.

“If you ask me, I won’t change my mind if I heard some woman died in Arab countries,” one returnee told researchers. “…Let me tell you I went to Dubai immediately after one woman from the neighbourhood died. My mother tried to stop me from going, but I said ‘no’. Nothing happened to me.”

When planning for departure, interviewees said they had focused on stories told by successfully returnees and downplayed negative reports about abuse.

“When we tell our bad experiences to prospective migrants they don’t trust us,” said one domestic worker. “They usually say ‘Why do you forbid us while you went there and returned back with money?’ … Most of us are not convinced unless we experience it ourselves.”

Although most returnees personally knew someone who experienced physical, sexual and psychological exploitation or had experienced it themselves first-hand, this was usually put down to “bad luck” of cruel employers.

The study, funded by anti-slavery group The Freedom Fund noted that, “for some, their intention to migrate seemed irreversible".

_______________

Read more:

Ban on Filipino domestic workers looks set to be lifted as new agreement with UAE is signed

FNC approves bill that limits domestic staff’s work hours

Draft law protecting domestic workers rights hailed by embassies

_______________

Advice included learning basic Arabic and cultural expectations before travelling, insisting on having a room with a lock and bringing a hidden mobile phone and local SIM card. Women advised prospective migrants to keep contact details of their family, agency and local Ethiopian families.

Returnees said training on using household appliances and cleaning supplies would improve safety and build confidence.

Confidence and polite assertiveness were seen as important characteristics to reduce the risk of mistreatment.

“It is advisable to prepare yourself to be confident, not to get confused with what you see or hear,” said one worker. “You have to convince yourself that you went there for work; you have to change your behaviour if it is necessary. If you are shy here you should no longer be shy there. Confident and strong characteristics help you to be tolerant and successful.”

Another returnee told researchers: “Sometimes they order you to eat their leftovers. At that time, I told her, ‘I don’t want to eat that’, and then she gave me fresh food. Even I started preparing my meals for myself. You have to be confident and ask for what you want.”

Finally, returnees advised women to set up a secure system for saving remittances.

The research will be used to develop the Amhara region Hotspot programme for prospective and returnee refugees.

“There’s only so much you can do in the country of departure so we’re trying to raise awareness,” said Ms Busza. “Ultimately, they’re not wrong when they say, ‘when I go overseas it’s up to what kind of employer I have’ or ‘it’s up to God’ or ‘it’s up to luck’. If there aren’t legal protections in countries for low-skilled workers, there’s only so much this preparation or training one can actually do. Workers around the world need protection where they are and need to be able to seek redress if there are cases of exploitation and abuse.”

“This is really a breakthrough and landmark proclamation,” said Hayat Abdu, a minister counsellor at the Embassy of Ethiopia. “I hope others will follow it. I’m afraid it may have challenges because, first, attitudes in this society do not put domestic workers on an equal level. The law provides them with many protections, including having an identification card, but the problem is that domestic workers are considered a lower level and cannot defend their rights.

“The other thing is they work in private houses and it’s difficult to control what goes on inside the house. Besides, the domestic workers may not know what rights they have.”

The Ethiopian government is in the process of signing a domestic workers agreement with the UAE and plans to make training mandatory for overseas domestic workers, as stipulated in the revised Overseas Employment Proclamation. The government will give workers at least least three months' training with classes on workers' rights and obligations, household appliance use, cultural norms and introductory Arabic.

The Ethiopian government has a standard domestic contract for all domestic workers who plan to work abroad that is signed by the agency, employer and employee. This contract guarantees workers' rights, like limiting working hours to eight hours a day. However, this contract means little once domestic staff arrive in the country of employment. Another contract may be signed and the original contract signed in Ethiopia ignored.

Agency employees said a smooth transition ultimately depended on the employee.

“If the employer is good, patient and they know how to teach people, then the people will be good,” said Rahel Atsbha, an Ethiopian who works in domestic staff placement at the Al Ahlia Labour Supply Services agency in Ras Al Khaimah. “These are people who are willing to work, they are willing to travel and leave their family. The problem is inside the house.”