My parents loved to travel when we were growing up, and they never hesitated to bring us along for the ride. By the time I was 10, I'd already been to France, Cyprus, Holland and all over the United Kingdom several times. I have to admit I don't remember much of those trips save what I think I remember from family photos: my sister and I in matching Snoopy bathing suits on a beach; swans by a cafe in Cyprus, exploring castles in the Scottish countryside; shopping on the high street with my mother.

But one thing I do remember vividly were the multiple museum trips my father would take us on, particularly when we travelled to England. Those solid Victorian buildings were always filled with treasures, stories and mystery. They seemed endless and massive, with rooms that never finished. My parents pointed out interesting parts of the displays, making sure to read out loud the explanations for each one. The ancient jewellery sections were invariably boring and the ancient mythology sections endlessly fascinating.

There was always an ancient Egypt section - and I have to admit they intimidated me a little. I recall lots of dark rooms and dirty linen-clad skeletons, with tales of tomb curses and descriptions of brains being pulled out through dead people's noses as part of the mummification process. It was all so interesting, but so unreal. I couldn't grasp the idea that these people had once lived and walked on the same planet that my family and I inhabited right now.

Those dimmed rooms and musty displays flashed back into my mind last week when, as part of a press junket, I was sent to cover the discovery of a new ancient Egyptian grave site. A photographer, driver and I left the chaos of Cairo for the green fields of Fayoum Oasis, about an hour and a half outside the capital. It is an agricultural area where people live quite simply, farming their land, selling crops and living in small communities. To get to the grave site we had to drive another half hour to Lahun village - a primitive and ancient community that dates back to the Middle Kingdom of the pharaohs. People still live as farmers here, riding their donkey carts with their wares under the watchful eye of the King Senusret II pyramid, a deformed hunk of rock created for the King in the Middle Kingdom (1991-1783 BC).

The area around the pyramid was excavated in 1889 but abandoned when the British archaeology team found little of interest. The site was revisited last November when a group of Egyptian archaeologists led by Dr Abdelrahman al Ayedi started digging. Dr al Ayedi said he was inspired to go back to the site because he had faith that there was something there to be found. Sure enough, four months later, he was standing in a baseball cap and worn out clothes, a pack of cigarettes in his shirt pocket, giving his workers orders to be careful as they dusted down the 53 tombs they had unearthed.

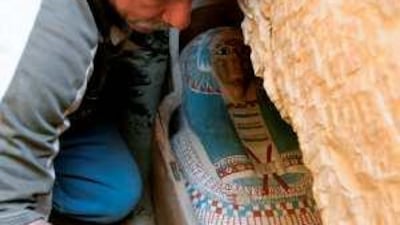

I stood on the barren hillside, along with my fellow journalists, and stared down as a couple of workers at the bottom of the three-metre shaft gently lifted the lid of a coffin inscribed with prayers in hieroglyphics. It seemed utterly surreal, the stuff of movies - that someone had placed this coffin in this tomb thousands and thousands of years ago and here we were today touching it! I couldn't grasp what was happening and it just became more unreal when the brightly painted sarcophagus of the mummy was revealed lying inside the wooden coffin.

The colours were preserved so well it looked like someone had painted it just a year ago - not thousands of lifetimes ago. The painted face of the mummy showed a young girl with Egyptian eyes lined with kohl and dark black hair. The red, blue, white and yellow inscriptions on the sarcophagus told us she was the daughter of one of the mayors of Lahun, and she had been buried with several of her possessions to help her get to the next world.

In another tomb, we were able to take a ladder and crouch down beside three sarcophagi laid out side by side. Three small women were buried here, and to one side was a broken coffin with strips of dusty linen peeping through the space between the lid and the body of the sarcophagus, just like I had seen in museums. Sitting in the cramped tomb, only inches from coffins that were possibly placed by family and loved ones, was eerier than those museum rooms.

The idea of entering the final resting place of a fellow human being sent a chill down my spine. The beautifully preserved sarcophagi and the intricate way the tombs were built were awe-inspiring, demonstrating just how sophisticated the pharaohs could be, and also how much effort and respect was dedicated to a dead person's grave. It gave me a newfound respect for ancient people that couldn't be found in any museum.

Hadeel al Shalchi is a writer for the Associated Press, based in Cairo