In its near 17-year existence, the World Anti Doping Agency (Wada) can lay claim to considerable achievements. But the cruelest way of judging the body would be to conclude that far from eradicating doping in sport, the incidence of doping seems to have increased in its time.

Here are some steps the body can take to become more effective in its fight.

Become independent

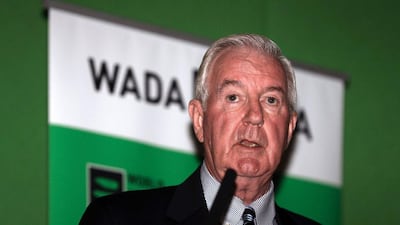

When Wada was about to be created, a United States White House drugs policy official said that the body could not be an independent one, given a structure that involved 50 per cent funding from the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the rest from national governments. Richard Pound, the body’s first president and an IOC member, wrote to the official and insisted that it would be.

The structure has remained the same and so too have the concerns, namely that there is an inherent conflict of interest in the IOC’s stake in Wada. The current Wada head Craig Reedie is an IOC vice-president. How can the IOC truly want Wada to work knowing that Wada working well means the Olympics’ integrity takes a hit?

And funding from national governments with their own agendas leave the question of conflicts more open than ever before. A new, independent structure has to be found for the body to work.

Grow some teeth

Richard Pound’s 325-page report on Russia’s doping regime for its track and field athletes also came to some pertinent conclusions about the body that he first led. Pound said that Wada had become “unduly tentative with signatories in requiring compliance and timely action” and too “diffident” in its attitude over the last decade.

Others have accused the body of not understanding or being willing to act upon the full scope of its powers. It has done this primarily because of the nature of its funding, but also because of its unwieldy structure.

Most of the biggest doping busts in recent times have come as a result of deep investigation – albeit by media houses – and not testing. What Wada needs is more investigators, who can work independently and in liaison with various drugs and law enforcement agencies around the world.

More money

A decade ago, Wada received US$20 million in annual funding. Last year it received US$26 million (Dh73.5m), which, given inflation, is hardly an increase. And it is certainly nothing like the increase in sponsorship revenues of the IOC in that period.

Given the amount of money lolling around in sports these days, US$26 million is a pittance, especially for an organisation with as wide and critical a function as this. If administrators are really serious about the fight against doping, then they are going to have to put their money where their mouth is.

osamiuddin@thenational.ae

Follow us on Twitter @NatSportUAE

Like us on Facebook at facebook.com/TheNationalSport