That the Negro Leagues ever existed as a part of American baseball is a shame on the country that no amount of passing years, nor glorifying of what was accomplished there, can erase. Yet its history is a snapshot in time, a reminder of America's long and ongoing battle between what is right and what is racist that stands as a testimony to the fire of the human spirit and the ability of sports and talent to change people's minds.

Before 1890, blacks freely played in what then passed as professional baseball, but after the rise of Moses "Fleetwood" Walker as one of the game's finest catchers in the mid-1880s, an abrupt change came over the game that would deprive blacks of opportunity for the next 57 years. Although there was never any formal prohibition, a gentlemen's agreement was reached in 1890 among owners of major and minor league teams to ban blacks from professional baseball. Within a few years more than 200 independent all-black teams existed but it was not until 1920 that a fellow named "Rube" Foster, owner of the Chicago American Giants, established what became known as the Negro National League. That same year another all-black league was formed in Nashville called the Negro Southern League.

The Depression soon caused those leagues to struggle until, in 1933, a gangster named Gus Greenlee saw opportunity and formed a second Negro National League to replace the one that had folded two years earlier. His interest was not totally in black baseball's survival, however. Greenlee's main interest was to use the league and his team in Pittsburgh to launder money he was making through illegal gambling operations. Four years after Greenlee reopened the Negro National League, a competitive Negro American League began and soon a Golden Era in black baseball had begun that would stretch from 1935 to April 18 1946, the day the Brooklyn Dodgers became the first major league team to hire a black ballplayer by signing Jackie Robinson.

As with Greenlee's resurrection of the Negro National League, the Dodgers' signing of Robinson was more a business decision than a tool for societal change. Although by then many major leaguers had played against blacks during off-season barnstorming tours and came to realise their talent, it was not until Dodgers' owner Branch Rickey signed Robinson that the complexion of baseball, literally and figuratively, changed forever. "The greatest reservoir of raw material in the history of our game is the black race," Rickey said that year, echoing what many major leaguers who had played against Negro League stars like Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, James "Cool Papa" Bell and Oscar Charleston had said for years. "If Oscar Charleston isn't the greatest baseball player in the world, then I'm no judge of baseball talent," Hall of Fame manager John McGraw once said. More importantly, in 1901, when he was managing the New York Giants, McGraw tried to sign a black second baseman named Charlie Grant, insisting he was a Cherokee Indian named Tokohoma. The ruse didn't work.

The prohibition against blacks in baseball was unbroken even after major league baseball formed a committee on baseball integration in March, 1945. It never held a single meeting.

"They used to say, 'If we find a good black player, we'll sign him'," Bell recalled many years after hitting .392 against white major league pitchers in off-season exhibition games. "They was lying." Life in the Negro Leagues was far different from major league baseball. Teams were made up of no more than 14 or 15 players to keep costs down. Travel was difficult, often by car or rickety bus during the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, with more players jammed inside than there were seats.

During the Depression and well after it, players would pass the hat among fans in the stands to raise money, dividing the proceeds among themselves after their travelling expenses had been covered. One of the Negro League's greatest stars was a muscular catcher named Josh Gibson. His home run power was so legendary he was called "the black Babe Ruth", a name his son later grew to hate, often asking: "Why wasn't Ruth the white Josh Gibson?"

In 1933, Gibson slammed a prodigious home run out of a local ballpark outside Pittsburgh that went over a flagpole and across a street, landing 470ft from home plate. In an article in the Pittsburgh Press many years later, the retiring mayor of a suburb of Pittsburgh recalled that day, saying there were around 500 people in the stands and when they passed the hat only US$66 (Dh243) was collected. After the umpires were paid, the two teams were left with $44. Gibson, the greatest player in the league, was handed $1.67.

Despite such difficulties, the existence of the Negro Leagues was for years a point of pride among American blacks who followed their league, not lily-white major league teams like the Boston Red Sox, New York Yankees or St Louis Cardinals. "Something great emerged from a difficult time in our society," said Negro League historian Bob Kendrick. One of the Negro Leagues top players, Buck O'Neill, became famous late in life talking about those days on a PBS documentary by the filmmaker Ken Burns that was part of a series Burns did on the history of baseball.

Of the importance of the Negro Leagues to blacks between 1890 and 1946, O'Neill said: "It meant everything to me, because I hadn't thought in terms of black and white, you know. All the professional baseball players I'd seen, they were white, you know. Now, I was going to see the professionals who were black and this meant so much to me. It meant getting me out of that celery field [where he worked as a boy in Florida]. It meant improving my life. I said, 'I'm going to be a baseball player'.

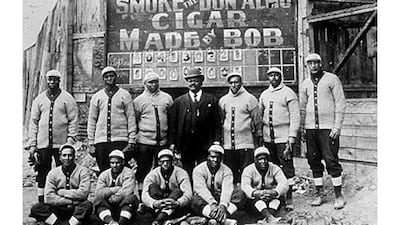

"Black people were proud, very proud. It was the era of dress-up. If you look at the old pictures, you see the men have on ties, hats, everybody wore a hat then. The ladies had on fine dresses. Just the way it happened. And one of the reasons for that was in our faith - Methodist, Baptist, or what not we had 11 o'clock service on Sunday. But when the Kansas City Monarchs were in town or when the East-West [all-star] game was on, they started church at 10 o'clock, so they could get out an hour earlier and come to the ball game. Came straight to the ball game, looking pretty. And we loved it."

Yet O'Neill recalled in a portion of that film that they were not always so warmly received in southern towns where segregation still held a firm grip on society. "It was terrible, really, in some spots," O'Neill remembered. "We got in the ballpark once in Macon, Georgia, and I got the stuff off the bus and went into the dugout and here's the Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. They're going to march on that field.

"So you know, when the Ku Klux Klan was marching that means all black people, you closed your windows, you brought the shades down and all. So he says 'You boys aren't going to play here tonight. We're going to march here tonight'. "I say 'Yes sir'. So we get back on the bus and go on. These were some of the things that we had to contend with." Despite all the difficulties, economic, racial and logistical, some of the country's best players were playing in this shadow league, known mostly only to blacks because there was little written about them in the mainstream press. Yet even then word leaked out about a pitcher as dominate as Satchel Paige or hitters like Gibson and Charleston.

"Satchel was the best pitcher I ever saw," the Hall of Fame Cleveland Indian pitcher Bob Feller said after the two engaged in what became a legendary string of exhibition games in 1946 between a team of Negro All-Stars and white major league stars. They battled on an even footing, ending any doubt among most players that blacks belonged in the major league. "After I got a hit off Satchel [in an off-season exhibition game] I knew I was ready for the big leagues," recalled Joe DiMaggio, one of baseball's greatest centerfielders.

By 1952, only six years after Robinson signed with the Dodgers, 150 blacks were property of major league teams. White owners had taken the cream of the crop. Nearly all the top black ballplayers young enough to make a career in the major leagues had abandoned the Negro Leagues. Although those leagues struggled on until 1960 they were effectively dead the day Robinson signed, ending one of the largest and most successful black-owned enterprises in America at that time.

Sport, as is often the case, was ahead of society in breaking the colour barrier in the United States. Baseball's fell in 1946 but it would be two more years before the same was true of the Armed Forces, which had been segregated even during World War II, and seven years before a Supreme Court decision integrated American public schools. Baseball, which had so long denied blacks, opened many doors, yet in a sad symbolic way, Josh Gibson, the greatest black ballplayer who ever lived, died at 35 - the same year Robinson signed with the Dodgers. The man who had once come within two feet of being the only player to hit a ball out of Yankee Stadium (during a Negro League game) had never had a bat in the major leagues. For him, integration had come too late.

"I played with Willie Mays and against Hank Aaron," recalled former Negro League and major league star Monte Irvin. "They were tremendous players, but they were no Josh Gibson." With their stars now gone, attendance dwindled. The attention of their fans was now on the major leagues, following former Negro League players like Robinson, Mays and Aaron, who was the last Negro League player to reach the major leagues before they disappeared. The Negro National League Greenlee formed in 1933 was gone by 1949 and the Negro American League was disbanded in 1962, but had ceased to really exist by the early 1950s in any practical manner.

With their passing, a sport and a country had changed for the better. O'Neill addressed the meaning of that change and why it had taken so long during Burns' PBS series when he was asked why the great white ballplayer Ty Cobb hated black players and fought their entrance into the major leagues. "I could understand Cobb," O'Neill said. "Ty Cobb had what the black ballplayer had. The black ballplayer had to get out of the cotton field. He had to get out of the celery fields and this was a vehicle to get him out. This was the same thing with Cobb. Cobb had to get out of Georgia. He had to fight his way out, and this was why he had this great competitive spirit and so what he's saying against blacks was the same thing that I think every poor white man had against blacks. Because we were competition to him.

"We weren't competition to the affluent, to the educated. No. But the other man ? we were competition to him. And Ty Cobb wasn't the only one. Ty Cobb just happened to have been an outstanding baseball player and felt that way, but a lot of other people felt the same way - the majority of people felt that way." As much as the Negro Leagues once meant to blacks like O'Neill, for whom they were the only opportunity in baseball, Robinson's signing meant more. It meant progress but it also meant the death of the Negro Leagues.

"Everybody was so happy about it," O'Neill said in Burns's film. "We'd been looking forward to this thing for years because we knew we had a lot of fellas capable of playing in the major leagues, see? And I believe that more than anything else what killed Josh Gibson was the fact that he couldn't play in the major leagues when he knew he was the best ballplayer in the world. See? We were all elated - it was the death knell for our baseball, but who cares?

"The only thing I didn't like - in the Negro Leagues, there were some 200 people with jobs. Now, these people didn't have the jobs anymore. We eliminated those jobs. But, still, I welcomed the change because this is what I'd been thinking about since I was that high. Rube Foster was thinking about this before I was born. The change that would make it the American pastime. But as to the demise of the Negro Leagues - it never should have been a Negro League. Shouldn't have been."

No, Buck, it shouldn't. rborges@thenational.ae