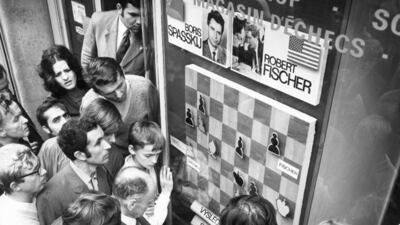

In 1972, millions of television viewers watched at least part of an event in which two men representing their respective nations were pitted against each other at the highest level of endeavour.

What was billed as the “match of the century” unfolded over a series of 21 games between July 11 and September 1, with the American contender stealing the world title from the defending champion, who hailed from the Soviet Union.

It had all the hallmarks of a huge sporting spectacular, with an exciting overlay of Cold War politics. But it was, in fact, a game of chess.

The new champ, Bobby Fischer, and his defeated rival, Boris Spassky, were more famous than many sportsmen of the day and, indeed, were the rock stars of their genre. But the series, for all its slow-motion thrills that were shown on the television news and analysed by experts on panel shows, failed to resolve a still-burning question: is chess a sport?

Certainly, it has many things in common with popular sports. It is a competitive activity in which the object is to win; it is played under codified rules; and in certain formats of the game, it is played within a time limit. Moreover, the governing body of chess, the Fédération Internationale des Échecs, is recognised by the International Olympic Committee. So, too, by the way, is the controlling body of the card game bridge.

But that doesn’t mean that you’ll be seeing either chess or bridge represented at the Olympics anytime soon. Or on prime time television.

And it’s highly unlikely that anybody reading this could name any of today’s leading chess competitors without consulting Google. Like Soviet communism and the Cold War, chess’s big moment on the world stage has come and gone.

So, what makes something a sport? Why do we collectively embrace some activities and elevate them into spectator events? Moreover, why do different people embrace different sports?

A friend once described basketball as “one tall guy taking a ball to one end of the court and placing it in a basket, followed by another tall guy doing the same thing in the opposite direction”. The team that wins, he says, is the one that does this more often than the other. And – to his mind – that is all rather boring. Tens of millions of Americans would disagree.

But Americans, on the whole, tend only to like the sports they invented. Despite its British origins – or perhaps because of them, since colonialism ended rather badly there – the United States has avoided the passion for cricket evident in the Indian subcontinent, Australia, South Africa and even on its doorstep in the West Indies. Instead, it has baseball, which culminates in a World Series in which only American teams compete (and, before you even think it, the theory that the series was named after The New York World newspaper has been thoroughly debunked).

In Australia – and nowhere else on the planet – a few million people are enamoured with something called Australian football (previously known as Australian Rules). Some critics from the rugby league-loving parts of that country refer to it as “aerial ping pong”, and a Belarusian friend who attended a game with me a few years ago said it was the “most ridiculous thing” she had ever seen. To be fair, when I was in Minsk, I had trouble understanding the attraction of the biathlon, a sport that involves people alternately cross-country skiing and shooting at targets.

Great sport, clearly, is in the eye of the beholder. And the tastes of those who participate in and regulate sporting codes often do not coincide with those of the people who like to watch sport in the grandstand or on television.

Take darts, for example. Arguably it takes more skill to land a small dart in a target than it does to throw a stick further than anybody else – and yet the javelin is an Olympic event and darts is not. But darts – and snooker and, more recently, poker – are regularly screened on television, while outside of the Olympics and small track-and-field meets, javelin might as well not exist.

Indeed, many sports thrive only in a bubble containing those who are competing at the Olympic Games and those who aspire to. They are never played by ordinary people just for fun. (“Let’s go down to the pool for a spot of synchronised swimming,” said nobody ever.)

Which brings me to the point that television networks should be more open to screening the games that real people actually play. I'm now thinking of a Monty Python's Flying Circus comedy sketch involving the Olympic hide-and-seek final. But who plays hide-and-seek these days?

Perhaps one day soon we’ll be switching channels from the English Premier League to watch the World Pokemon Go Championships instead.

bdebritz@thenational.ae

On Twitter: @debritz