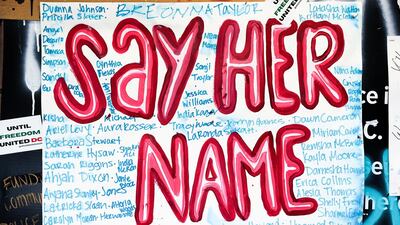

As protests following the murder of George Floyd started to gather momentum during the summer, I felt the compulsion to speak up for the anti-racism movement.

I have been publicly highlighting systemic racism for more than 15 years. As a Muslim, and as someone of South Asian heritage, I know what it feels like to be fooled into believing that you are simply imagining your oppression.

But the summer was not the moment to speak out about personal experiences. I held my tongue. This was the moment for black communities to speak about their experiences of racism. And while the movement began in the US, it quickly gathered global momentum.

I took the view that my role at that moment, as a Muslim and as a person of colour, was to stand as an ally with my black brothers and sisters. But it was also about more than that.

It was also about wanting to confront racism in my own communities. Because the truth is more people are racists than they admit or even realise, and it is not easy to talk about. Like everyone else, some people of colour and some Muslims, too, hold racist views. It is hard to say, but say it we must.

Remaining silent allows discrimination to advance. Silence from people in my positon makes us complicit of racism – regardless of skin colour, religion or ethnicity. By not speaking up, we show that we are either uncaring or oblivious to the fact that we are agents perpetuating racism.

When some Muslims are challenged about their own biases against people of colour, a familiar response is to hold up the example of the esteemed companion of Prophet Mohammed, Bilal, who was black, as supposed evidence of racial harmony among all Muslims. Or to state that Islam is a brotherhood that sees beyond colour and race, all the while continuing without irony to demean black people.

People who are of colour but not black bristle at the notion that we might be upholding racist structures – the very same structures that we complain oppress us.

My family heritage is East African Indian, so I know first hand the history of how Indians were established as intermediaries between white colonists and black ‘natives’.

This conferred a sense of superiority among some East African Indians, keen to believe that there is something inherently better about us, while oppressing black people. This hierarchy is exactly how racist structures are entrenched and proliferated.

Regardless of their own skin colour, nobody wants to think of themselves as racist, particularly those who themselves may have been at the receiving end of racism, sexism, Islamophobia and other discriminations. So I understand that these are difficult and sensitive conversations.

October is Black History Month in the UK and parts of Europe, which makes it a perfect time to have these discussions with honesty and respect.

Dating back to the 1980s, the month’s aim was to offer a fresh perspective on the history that dominated British school teaching, with the goal of challenging racism.

It has broadened out since then to celebrate the contribution of black people and to nurture a deeper insight into black history. It drew on the American institution of Black History Month, which dates back to the 1920s and takes place in February every year.

Any other people of colour inclined to react to this takeover of the upcoming month with "what about me and my heritage" need to realise that it is not about us, but about black people and starting on a journey to equality and humanisation.

And if we can’t do it for altruistic reasons or the fact that it is intrinsically right, then we should understand that it is in our own interests to destabilise racist hierarchies. This is exactly what Black History Month sets out to do. That is why I will be soaking up all the cultural events in the coming weeks.

I was brought up with only a little knowledge of the history of East Africa, where my family lived for over a century. And shamefully, my knowledge of black British history is more limited than I would like – even though, in recent years, I have been working to rectify this.

I am only speaking for myself here, but I have found that by listening with an open heart and mind to the experience of black communities, one develops a stronger sense of humanity and a sharpened sense of one's own identity and place in the world.

Shelina Janmohamed is an author and a culture columnist for The National