The tiny speck of light currently on display in Louvre Abu Dhabi, part of a recently opened exhibition called 10,000 Years of Luxury, represents the oldest known pearl in the world. This 8,000-year-old pearl was unearthed on Marawah Island about 170 kilometres west of Abu Dhabi and still has its natural lustre.

As small as it is, tells a remarkable story, stretching back to the dawn of civilisation when the Neolithic way of life was taking root in the lands of the Emirates. Together with the sherds of pottery, bones and shells found by archaeologists at sites across the region, it has helped build a picture of what life might have looked like in the Emirates thousands of years ago.

The Neolithic revolution was set in motion by the end of the last Ice Age. It began in the Fertile Crescent – the river-valleys of Iraq and Egypt connected by the Levant – about 14,000 years ago. Primordial hunter-gatherer societies slowly gave way to settled farming or nomadic herding communities. Land ownership guaranteed by new weapon types and religious ideologies forever transformed human societies.

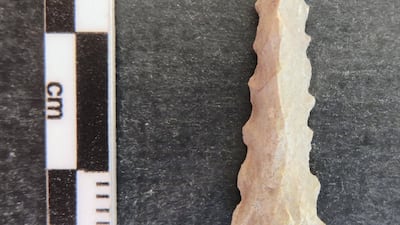

By about 10,000 years ago, the Neolithic revolution was beginning to reach the emirates. Flint arrowheads found at Jebel Faya in Sharjah belong to a Neolithic toolkit imported from the Fertile Crescent. It seems that groups of nomadic pastoralists were moving southwards from Syria-Palestine, possibly driven on by population growth triggered by the Neolithic way of life. This Holocene, or post-Ice Age, repopulation of Arabia likely provided the baseline gene pool of the Emirati people.

A pioneering Neolithic village was established on the island of Marawah in the emirate of Abu Dhabi about 8,000 years ago. Three structures have so far been located. They were built of local limestone and one has an oblong plan. The upper sections of the walls and roofs were probably made of palm fronds. Similar structures have been found at the contemporary site of Al Sabiyah in Kuwait.

These stone-built houses can be contrasted with palm-frond roundhouses at Delma Island in Abu Dhabi and Suwayah in Oman. Analogous palm-frond structures have been found at the settlement at Akab in Umm Al Quwain. Differences in domestic architecture could be indicative of the co-existence of distinct cultural groups in the emirates at the time.

The Marawah pearl dates from 5,800 to 5,600BC. It therefore predates the previous oldest pearl in the world by several centuries, found in Al Sabiyah and dating to 5,300BC. Prior to the discovery of the Marawah pearl, the oldest found in the Emirates was at the settlement of Akab, which flourished between 4,750 and 3,900BC.

Pearls are not infrequently found at Neolithic coastal settlements in the Emirates, which include Yarmouk in Sharjah and the archaeological site of UAQ2 in Umm Al Quwain. The largest number of pearls ever found at a prehistoric site actually come from the interior, from the cemetery of Jebel Al Buhais in Sharjah, where 62 pearls dating from around 5,000 to 4,500BC were discovered.

Many more pre-modern shell middens, or archaeological mounds, dot the coastal landscape of the Gulf. Some of these date to the Neolithic period and are broadly contemporary with the Marawah pearl. One of the largest – a three-metre-high mound densely packed with shell fragments – was found at Dosariyah in Saudi Arabia. The number and size of these middens give some indication of the potential scale of pearl fishing in the Neolithic period.

No evidence has yet been unearthed, however, for Neolithic methods of pearl fishing. It is certainly possible that boats were already being used to transport divers to the pearl beds and that the divers were using weights to sink rapidly to the bottom of the sea, as was the case in later periods. Alternatively, oysters could have been collected by wading from the shore at low tide, a practice which continued into living memory in the Emirates.

Oysters and other shellfish were an important source of food for coastal communities. It is unclear to what extent oysters were fished specifically for their pearls. Certainly some of the pearls from Neolithic sites around the Gulf were pierced and turned into jewellery, as was the case with the Al Sabiyah pearl and those found adorning the dead at Jebel Al Buhais.

It has often been supposed, largely on the basis of analogies with better-known historic periods, that the pearls were traded beyond the Gulf. However, no pearls have yet been found in Mesopotamia – the region of southern Iraq where complex urban civilisation first emerged – prior to the Bronze Age in the third millennium BC.

Pottery provides the best evidence for trade with Mesopotamia. The Neolithic communities of the Emirates had no knowledge of ceramic production and imported fine-bodied decorated pots made in and around the site of Tell Al Ubaid in southern Iraq. One of the most celebrated examples is the Marawah vase, now in Louvre Abu Dhabi.

Sherds of Ubaid pottery are found all along the coast of eastern Arabia. It is possible these were traded directly or, perhaps more likely, via one or more middlemen. By the Bronze Age, Bahrain had emerged as a commercial hub of Gulf trade: the legendary land of Dilmun. This trade constitutes one of the earliest maritime networks in world history.

Evidence for early seafaring has been found at Al Sabiyah. Fragments of bitumen bearing the impression of reeds on one side, with barnacles adhered to the surface of the other, suggest that Neolithic boats were made of reed bundles coated with bitumen. A small clay model of a boat from the site gives an impression of how these vessels might have looked.

Trade was nevertheless only a part of the Neolithic way of life. It is possible that palms were already being grown, as suggested by two carbonised date stones found at Delma Island. Dates may alternatively have been imported from Mesopotamia, as indeed they were until recent times. Farming does not appear to have become significant in the emirates until the Bronze Age Umm Al Nar culture beginning around the mid-third millennium BC.

Over 90 per cent of the bones found at butchery sites at Jebel Al Buhais are from domesticated sheep, goat and cattle, indicating the declining importance of hunting. Most of the sheep and goat were elderly females, suggesting that they had been kept for their milk. The picture emerges of a nomadic herding community moving to Buhais for the lambing season in the spring and spending the summers fishing on coastal and island settlements like Akab and Delma.

It is Jebel Al Buhais too that provides the most complete picture of Neolithic life in the emirates. About 500 individuals were found buried in the cemetery. A study of the human remains revealed that the average life expectancy for women was 33, compared to 40 for the men. More women than men died in their teens and twenties, owing to the dangers of childbearing, while the skeletons of the men displayed a greater occurrence of near or before-death trauma associated with a violent death.

Many of the individuals buried in the Buhais cemetery wore pearls and it is possible that the Marawah pearl was somehow lost before it could be pierced and worn. Alternatively, it was lost before it could be shipped to Mesopotamia in exchange for manufactured goods and agricultural surplus. In either case, the pearl opens a fascinating window on life in the emirates during the Neolithic period.

Timothy Power is an archaeologist, historian and author of A History of the Emirati People, to be published in 2021