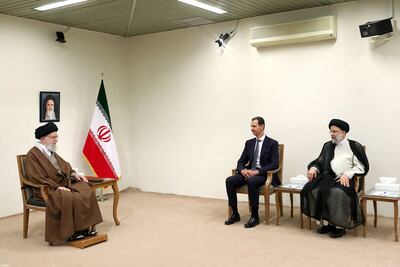

Many have wondered how, in the aftermath of the recent Chinese-brokered detente between Saudi Arabia and Iran, to think about efforts by Arab states to reintegrate Syria into the region. How might Syrian President Bashar Al Assad’s relations with Iran and Hezbollah affect any rehabilitation? Are we seeing today the components of a roadmap being drawn that would mean a substantive — not just ceremonial — Syrian return to the fold?

Saudi Arabia will host the next Arab League Summit, taking place next month, and is thought to be drafting a pragmatic agenda that complements the new vision and approach of the Saudi leadership. It is an approach that does not rely on improvisation — far from it. Riyadh’s messaging is coherent, even if brief.

Mr Al Assad gradually needs to escape the Iranian grip, because he will not be able to be fully in control of any Syria that lies in the shadow of Iran’s continued dominance. Therefore, he may find that a relinkage with the Arab states — gradually, and as part of a regional deal — will be his salvation from total reliance on Iran and Russia.

Arab states’ offer to Mr Al Assad is thought to include a pledge to help rebuild Syria, to ease its isolation and to create a bridge between it and the outside world. It also includes collective efforts to gradually contain Turkey’s influence, as well as Iran’s. In the view of many countries in the region, greater Arab influence in Syria could be reassuring to Syrians, and it would be in Mr Al Assad’s interest to be part of that effort to reassure instead of antagonising his people. But such an outcome would likely only be achieved in return for binding commitments from Mr Al Assad. These are the elements of a serious deal, not a mere reunion.

In terms of his relations with Hezbollah — which fought alongside Damascus against the Syrian opposition and has become his partner along with Iran — Mr Al Assad would likely be required to gradually disengage.

It is possible, particularly in the aftermath of the Iran-Saudi detente, that Iran would allow some political change in Syria, and that Russia would not mind it. Indeed, Moscow today sees Syria as a burden, and it needs to focus its energy on the war in Ukraine.

But why would Iran agree to such a radical shift? For one thing, it needs to overcome its economic dire straits, as well as its nuclear crisis, which makes it vulnerable to military confrontations, and its political isolation. Therefore, Iran may agree to concessions in the framework of a deal to normalise relations with other Arab states and secure the economic relief this entails, as well as the possibility of US sanctions relief if it abides by its commitments and radically softens its behaviour.

US President Joe Biden’s administration is somewhat troubled by the developments in the Middle East that have put China in the driver’s seat, but, at the same time, Washington is not completely opposed. Indeed, it has said it welcomes developments that could help avert conflict with Iran.

Moreover, the Biden administration is understood to be in favour of Arab states replacing the Astana process led by Russia, Turkey and Iran, by sponsoring a political process in Syria and working to persuade Mr Al Assad to make concessions to the opposition.

It would also be a welcome development for the Biden administration if the efforts of Arab countries that have normalised relations with Israel succeed in creating a climate that could gradually bring Syria into a comprehensive process of de-escalation in its outstanding conflicts with Israel. Today, the broad strategy of Gulf states, in particular, is to reduce, avoid and resolve conflicts throughout the Middle East, through a gradual approach and a qualitatively different kind of diplomatic engagement.

The aspirations of Saudi diplomacy were explained by Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman during the Future Investment Initiative meeting in Riyadh in 2019, when he spoke about the dream he intended to turn into reality by transforming the Middle East into another Europe, becoming far removed from ideological conflicts and extremist policies. Then in the Jeddah Security and Development Summit last year, attended by leaders from the GCC, the US, Egypt, Iraq and Jordan, the Crown Prince affirmed a vision that prioritises security, stability and prosperity, calling on Iran to work with the countries of the region and become part of that vision. Saudi Arabia’s hosting of the Arab League Summit in May will be another important milestone in the context of the pragmatic implementation of this vision, especially in the wake of the agreement with Iran. And Syria could be a testing ground.

If, as many expect, Mr Al Assad is truly ready to replace his reliance on Russia, Iran and Hezbollah with domestic reforms, dialogue with the opposition and accepting the return of Syrian refugees, then regional diplomacy will have delivered a coup. The key, however, is honest and true implementation.

This will not be easy for Mr Al Assad, even if he is persuaded, to get permission from Tehran, which has been a strategic partner for Damascus for decades, to become more independent. Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps may not be ready to end its pact with the regime in Syria and Hezbollah in Lebanon. This is where the problem lies: Iranian dominance in Syria is a strategic goal for Tehran, and the IRGC commanders will not favour being part of any reduction of their country’s footprint there.

Whatever happens, it is likely to happen only gradually, say those familiar with the process. Just as well — let caution be the compass to trust, and let trust be the destination.