In the wake of Donald Trump’s Syrian air strike, White House officials told The Washington Post that the president was motivated by compassion for the more than 80 victims, including many children, of a chemical weapons attack carried out by Syrian president Bashar Al Assad on his own people. Pictures of the victims of the attack on Khan Sheikhoun so moved the US president, the story went, that he authorised the launching of 59 Tomahawk missiles from warships stationed in the eastern Mediterranean, their target being the airfield from which Mr Al Assad’s own attacks had been launched.

The US missile strike has garnered nearly universal praise, including from outspoken Trump critics. The reaction of the US press has been nothing short of ecstatic, with adulation being offered in print and on air for the man who characterised – and still characterises – that same press corp as filthy, dishonest “enemies of the American people”. Commentators have called the missile strikes “presidential” and “decisive”.

All the natural historical comparisons tempt, but of course the real prompt here is very recent history: 2013, when Barack Obama warned the Syrian leader against precisely this kind of atrocity, deploying chemical weapons against civilians in his own country. Mr Obama infamously called it a “red line” and warned of prompt retaliation if it were crossed. And when Mr Al Assad crossed it, he did nothing.

Frustration over that inaction is a big part of what we’re seeing now in all this praise of Mr Trump.

Former Obama heavyweights such as John Kerry and Hillary Clinton have applauded Mr Trump’s action right alongside long-time enemies like senator John McCain. The US failed a moral test four years ago, the implication goes, and has now passed it in 2017. A clear message has been sent.

Instead of debating the rightness or wrongness of a US president launching missile strikes on a sovereign nation because of something he saw on TV, the question taken up by political operatives and the punditry has been: what happens next?

Was the Al Shayrat missile strike an isolated rebuke or part of the bigger picture of Mr Trump’s response to the ongoing civil war in Syria? How would the US respond if Mr Al Assad repeated his crime?

These are exactly the kind of questions Mr Trump wants, and it can be assumed he prefers them to the kind of questions he was facing in the press and on Capital Hill before Thursday.

Gone, for now, are the headlines about ethics violations, gone are the leading articles about administrative ineptitude, gone are the editorials about record-low approval ratings, and especially back-burnered is any talk about the ongoing congressional investigations into the extent Trump colluded with the Russians in order to win his electoral college victory in 2016.

Instead, the national and international headlines have been almost universally pro-Trump.

According to US intelligence officials, the Syrian military knew about the timing and location of the missile strikes ahead of time, and Mr Al Assad’s fighter planes were taking off from Al Shayrat only hours after the strike – largely because, as Mr Trump clarified, he intentionally left the air strips intact.

And Mr Trump’s own officials couldn’t agree on what the strikes had meant in the short- or long-term.

Rex Tillerson, the secretary of state, initially told the press that the Trump administration had no intention of pursuing the kind of regime change Mr Trump himself had derided Obama for advocating, but Nikki Haley, Trump’s ambassador to the UN, told the press the exact opposite, describing regime change as the administration’s goal. More recently, Mr Tillerson has suggested the Assad era was “coming to an end”. And the veracity of the TV clips allegedly sparked the president’s moral outrage is, to put it mildly, questionable. Since Mr Trump hasn’t divested himself of his business holdings while in office, he’s substantially richer after the missile strikes he ordered, as he’s a stockholder in the company that makes the missiles and experienced an upsurge in trading as a result of those strikes.

The strikes themselves make an incalculably dangerous situation in Syria just a bit more dangerous – not because they even so much as inconvenienced Mr Al Assad in his war against the rebels who now control half his country, but because they can easily be seen as a sign of US encouragement to those rebels, some of whom are every bit as bad as the leader they seek to topple.

The situations in 2013 and 2017 are identical in all respects but one, the most important of them all: the man in the Oval Office. In 2013 that man was a Nobel laureate with a penchant for overthinking even simple policy matters.

In 2017, that man is someone who can swing from one position on an issue to the opposite position in the course of one sentence.

Someone who famously decried in 2013 exactly the kind of action he himself has now taken in Syria in 2017; someone who can be, as his opponent memorably put it in 2016, “baited by a tweet” – or, he’d have the world believe, by heart-rending video on TV.

There’s a strong argument to be made that this last motive can be disregarded. And in any case the motive is irrelevant; in one thing the pundits are correct: the important thing now is what happens next.

Days after the missile strikes, that speculation groped for historical examples of American moral heroism, however piecemeal or tardy.

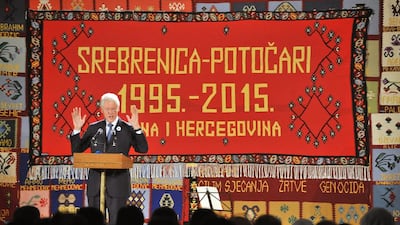

Bill Clinton’s decision to intervene in Bosnia in 1995 has come up. But those days have also seen new developments, the most alarming of which was a declaration by Mr Al Assad’s most powerful patrons, Iran and Russia, that another such missile strike by the US would be “met with force” – would be, in other words, considered an act of war. And just that quick, the historical parallels shift from Bosnia or Rwanda to Sarajevo in 1914, when the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand triggered a cascade of face-saving and sabre-rattling that quickly made all-out war unavoidable.

Will the US – and presumably its allies, despite Mr Trump’s mistrust of Nato – go to war with Russia over Syria?

The posturing of which Mr Trump is an advocate is the cheapest and deadliest of diplomatic skills, and Vladimir Putin was a master of it while Mr Trump was still a reality TV star.

The usual recourse for the rest of us would be to hope that cooler heads prevail, but it feels like a particularly reedy kind of hope these days.

Steve Donoghue is a regular contributor to The National