Live updates: follow the latest news on Joe Biden's Middle East visit

Former president Jimmy Carter's pledge that the US would intervene militarily if needed to ensure the security of the Gulf is now outdated as US policymakers redefine Washington's already shrinking role in the region, political analysts say.

The common view is that the void left by the US can be filled by joint security and military co-operation between regional powers, which have become increasingly self-reliant amid the reality of an American focus on China and Russia.

“The Carter Doctrine is no longer relevant for US engagement in the Middle East today — in large part because of the increased military capacity within the region itself,” Brian Katulis, a senior fellow and vice president of policy at the Washington-based Middle East Institute, told The National.

The pledge of protection was made by the 39th president of the US in January 1980, one month after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

Mr Carter set it as the basic tenet of American foreign policy in the Middle East, as it was widely believed that the former Soviet Union represented a threat to US interests in the Arab world.

It was associated with a Cold War mentality and also driven by the 1979 revolution in Iran.

Given the landscape of the Middle East at the time, the US stepped up its role and created much of the present-day infrastructure for engagement in the region.

“That was then. We're now in a transition phase redefining America's role — it's one that began years ago and it will continue to evolve in the next few years, increasingly driven by actors within the region,” said Mr Katulis, who has advised US policymakers and provided expert testimony to congressional committees.

The latest sign of the US's shrinking role in the Middle East and beyond was its withdrawal from Afghanistan in August last year, allowing the Taliban regime to return to power 20 years after being toppled by a US-led invasion ordered by former president George W Bush to hunt for Al Qaeda and its leaders.

In 2011, former president Barack Obama announced the complete withdrawal of the 160,000-strong US force in Iraq after eight years of occupation.

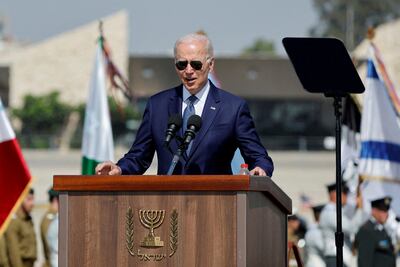

The incumbent US President, Joe Biden, who is visiting Israel, Palestine and Saudi Arabia this week, pledged in his campaign for the 2020 election to end the US’s “forever wars”.

Although the US today has only about 2,500 troops in Iraq, mainly for training and security co-ordination with Iraqi military and security services, there are still 45,000 to 60,000 US military personnel stationed at bases, airfields and outposts across the region, according to estimates cited by US media outlets.

Bahrain hosts the headquarters of the US Navy's Fifth Fleet, while the US Air Force operates out of the Al Udeid base in Qatar.

Refocusing goals in the region

Key and traditional allies in the region were disappointed when the Obama administration secretly negotiated and in 2015 signed a nuclear deal with Iran that did not address its ballistic missile and drone programmes.

The deal was reached in talks that did not include the concerns of Arab states and was seen as counter to the basic tenets of the Carter Doctrine. The perception of US disengagement and inaction has gained ground in the region since, particularly after a string of missile and drone attacks by the Iran-aligned Houthis in Yemen on Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi.

“US policymakers need to correct that impression, as Washington's network of relationships and interests in the Middle East still matters — especially in the aftermath of Russia's invasion of Ukraine,” Jason M Brodsky, policy director of United Against Nuclear Iran, an American advocacy group, told The National.

A pledge to deny Iran atomic weapons in the US-Israeli joint declaration signed during Mr Biden's visit on Thursday is seen as a sign of American resolve to refocus on the threat from Tehran after the collapse of the 2015 deal. Former president Donald Trump quit the pact aimed at curbing Tehran's nuclear weapons capability in 2018, deeming it insufficient, a move welcomed by Israel.

Mr Biden said after arriving in Jerusalem on Wednesday that he remained committed to resurrecting the nuclear deal, saying “the only thing worse than the Iran that exists now is an Iran with nuclear weapons”.

In an interview with Israel’s Channel 12 TV, Mr Biden said the US would not allow Iran to gain a nuclear weapon and would use military force as a “last resort”.

“Some of the logic of the Carter Doctrine as it relates to US interests still holds, but US presidential administrations have undermined it with their actions. It is time to update it not only rhetorically but also in terms of actions. President Biden's visit to the Middle East is an opportunity to do just that,” said Mr Brodsky.

Last month, Israeli Defence Minister Benny Gantz said his country was building a US-sponsored regional air defence alliance, an effort he suggested could be boosted by Mr Biden's visit.

Mr Gantz did not mention which countries were involved and regional heavyweights have not commented on his statements.

Israel has recently established ties with the UAE, Bahrain and Sudan, and re-established relations with Morocco, after the landmark 2020 Abraham Accords that helped reshape Middle East geopolitics and alignments.

But previous talk about regional alliances has not led to any concrete steps or the creation of a formal structure such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, says Yezid Sayigh, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Middle East Centre in Beirut, where he leads the programme on Civil-Military Relations in Arab States.

“There has been no success in forming formal multinational military alliances: witness talk of a Nato-Gulf body — discussed in Istanbul over a decade ago; a Saudi attempt to forge an Islamic defence alliance around 2015; and more Egyptian efforts to create a collective defence forum. I don't expect that to change,” he said.