Scientists have discovered a new way to produce blood cells that could pave the way for regenerative therapies for serious illnesses.

The breakthrough has the potential to help screen drugs, simulate diseases such as leukaemia and create blood stem cells for transplants, researchers said.

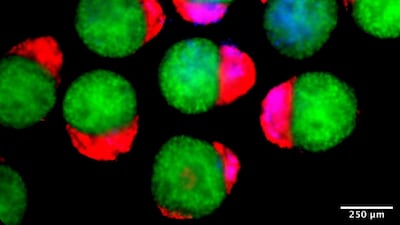

The embryo-like structures – called hematoids by the University of Cambridge experts who developed them – were created using human stem cells.

They simulate the changes that happen at the earliest stages of human development, when the organs and blood system starts to form.

The hematoids started producing blood cells after around two weeks in the lab, mimicking the process in human embryos.

However, the model differs from real human embryos and cannot develop further as they lack certain tissues, as well as a yolk sac and placenta.

Dr Jitesh Neupane, a researcher at the University of Cambridge’s Gurdon Institute and first author of the study, told The National the potential was “exciting”, as opportunities to study how blood and immune cells emerge open up.

He said the breakthrough helps “explore how blood disorders might arise during early human development, and in the long-term could eventually guide regenerative and therapeutic approaches”.

Prof Azim Surani, also of the Gurdon Institute, said: “Although it is still in the early stages, the ability to produce human blood cells in the lab marks a significant step towards future regenerative therapies – which use a patient’s own cells to repair and regenerate damaged tissues.”

By the second day in the lab, the hematoids had organised themselves into the three layers that are crucial for shaping every organ and tissue in the human body.

By day eight, cells that eventually form the heart in a developing human embryo had appeared and by day 13, red patches of blood appeared in the hematoids.

The study, published in the journal Cell Reports, found the blood cells in hematoids developed to a stage about the same as week four to five of human embryo development, which cannot usually be observed.

Co-first author Dr Geraldine Jowett said: “Hematoids capture the second wave of blood development that can give rise to specialised immune cells or adaptive lymphoid cells, like T cells, opening up exciting avenues for their use in modelling healthy and cancerous blood development.”

The team has patented its work through Cambridge Enterprise and the study was funded by Wellcome.