Governments in the region did not take cyber security seriously a few years ago. Now, after a drumbeat of public revelations of networks being penetrated around the world, many governments in the region have created cyber security systems and programs.

Middle East governments, however, did not learn from the mistakes made in the United States, Europe and Asia. Just like the countries that were early adopters, Middle East governments have placed their initial focus on offensive capabilities and, to a lesser extent, on securing some government networks (chiefly those involved in security).

What has been left largely undefended are private sector companies, infrastructure operators and civilian ministries. Yet they are the most frequent targets for sophisticated hackers seeking to steal money, identity, intellectual property and valuable financial information. Moreover, it is by attacking the infrastructure operators that an enemy could cripple an economy or a nation.

What would happen to any GCC country if a cyber attack significantly degraded or disrupted the electric power grid, the water desalinisation and distribution system, the oil and gas pipeline network, air traffic control or airline operations, hospital networks, banking systems, stock markets or even motorway traffic controls? Imagine any GCC city deprived of its mobile telephone system or connectivity to the internet for just a day.

These are not theoretical possibilities. Such infrastructure networks have been attacked and penetrated around the world. Often, such networks will collapse on their own for hours at a time. A concerted attack could take them out for weeks at a stretch. Countries with cyber war units routinely penetrate such networks just in case they may be called upon by their national leaders some day to deliver damage or destruction.

And it is not just the threat of damage occurring some day that should worry governments in the region. Every day companies and governments are put at a competitive disadvantage by the theft of information from their networks. Almost none of the companies involved even know that their networks have been compromised.

We know from years of experience of examining network penetrations throughout the world that even the most sophisticated corporate information security operations fail to detect sophisticated attacks. In the US, the country where the data is most readily available, more than two thirds of companies that were penetrated did not ever discover that fact themselves. They were informed either by a government agency or by the internet service provider. Other data from the US indicates that the average length of a network penetration of a corporation is 278 days before discovery. And that’s the average. In some cases, the penetration goes undetected for years. One bank that was penetrated by a hack was spending $250 million a year on cyber defence and had more than 1,000 full time, dedicated, cyber security staff.

There is no such granular data about the situation in the Middle East, but there is every reason to believe that it is the same or actually even worse. In Europe, East Asia and the Pacific, and North America, government agencies have created a series of compulsory regulations that force corporations engaged in critical sectors and in infrastructure to engage in serious cyber security efforts. There is little such regulation in the Middle East. There is less money being spent of the defensive side of cyber security, and there are fewer experts dedicated to protecting networks in this region than in comparable countries elsewhere. This condition is despite many countries in the region being even more dependent upon cyber-controlled infrastructure than those with older systems.

Rather than placing their emphasis on offence, governments in the region ought to be focusing on defending their infrastructure and critical corporations from cyber attack. That would mean creating expert government organisations to come up with standards and regulations and enforce them through audits. Such agencies should also evaluate technology, test networks, share information and develop a cadre of personnel experts in defending networks.

If, one day, none of the critical corporate and infrastructure networks in your country work because they have been hit by disruptive and destructive cyber attacks, the fact that you may have some offensive capability of your own will not really help you restore your country to minimum operations.

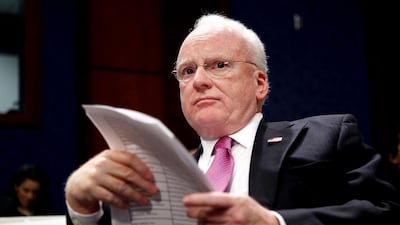

Richard Clarke, the chief executive of Good Harbor Security Risk Management and former national coordinator for security, infrastructure protection and counter-terrorism for the United States, will be delivering a keynote speech at the RSA Conference in Abu Dhabi on Thursday, November 5.

business@thenational.ae

Follow The National's Business section on Twitter