The energy industry is a cool place to work. At least that is what the generation that came into the industry in the 1970s and the early 1980s thought. Of course, that was before Yahoo, Google, Facebook and six-figure Wall Street bonuses started to compete for the very best of aspiring graduate brains.

Our hair is a little shorter and a little greyer, but that enthusiasm for the exciting pioneering work of the energy industry still runs through the veins of my generation. We have an obligation to use the last decade before our retirement to communicate that drama to a new generation and ensure we leave the business well supplied with talent and ideas for the future.

Time is short, especially when you bear in mind that the historical source of petroleum engineers has been the West. Since the 1970s, 40 colleges in the United States, the world's largest energy consumer, offered degrees in petroleum engineering. Today, there are fewer than 20.

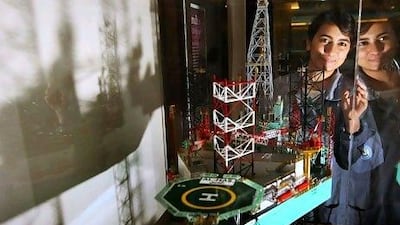

The development of local national talent in countries rich in energy resources across the world, especially in the Middle East, is one of the key ways for the global industry to mitigate the pending talent crisis.

Qatarisation, Emiratisation and Saudisation are becoming familiar terms as resource-rich countries set national quotas for international partners to employ locals. It is a vital tool to ensure that resource holders reduce their dependence on foreign talent and have the skills domestically to manage and develop their vast hydrocarbon resources through the 21st century.

These initiatives guarantee career paths for Arab nationals to enter and progress through their countries' respective energy industries, but I would recommend that these nationalisation programmes include a requirement for the young Gulf Arab petroleum engineers and geoscientists to work abroad to garner vital experience.

Otherwise we will not drive forward the kind of indigenous technological development and skills that we need to see emerge in the Middle East to manage the third generation of resource extraction in what many refer to as post-easy oil.

In Qatar, the nationalisation programme is, by decree, designed to increase to 50 per cent by 2015 the Qatari proportion of the energy-sector workforce.

This presents a great challenge, given the increasing career options that are open to young nationals in a diversified economy that is seeing consistent double-digit growth, and given the limited number of appropriately qualified graduates leaving the region's academic institutions.

It is true that you can develop talent within a closed environment of a degree course and then spin that talent out to work in a particular national industry. What emerges in the end, however, is a narrow experience profile. And so, as we get into the world of enhanced reservoir production in the Gulf, much of the experience to handle that will still need to come from afar.

When you are drilling a 12,192-metre horizontal well into a high-pressure reservoir, you cannot turn up with someone with a degree and just a few years of experience working in a simple production environment.

You can guarantee big salaries and new technology, but more money is not a replacement for experience in an industry full of operational challenges. The increasing cost of failure, in monetary and environmental terms, cannot be ignored.

Technology is not a panacea. It is part of the story, but it has to be employed in collaboration with the mitigation of the general risks that are associated with its application, and that starts with answering these questions: Where are we going to get people? And where are they going to get access to the appropriate experience?

I came into the industry in the early 1970s with the development in the North Sea. At that time, young engineers out of Britain and Europe were considered inferior to the talent that was being exported from North America. Today, European engineers from Scotland, Norway Denmark and elsewhere are succeeding all over world with the unique experience garnered from developing the highly complex and challenging North Sea environment.

You can build a tanker designed to haulliquefied natural gas in three years, you can build one of the world's most advanced deepwater drilling ships in three years, but you cannot develop a person in anything remotely close to that time frame to take on the responsibility and accountability that is needed to manage the processes of wells costing a minimum of US$100 million (Dh367.3m).

It will take 10 to 15 years from the person leaving university before to becoming competent to take on technical managerial and operational responsibility.

James McCallum is the chief executive of Senergy, an integrated global energy services company specialising in the skills associated with the identification, quantification and extraction of hydrocarbon structures