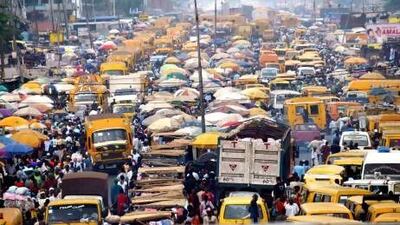

An ancient bus crawls along a dirt track, luggage piled dangerously high on its roof. The sight is so typical of Africa that tourists have come to expect it. But for Africans, poor roads are yet another poverty trap.

With few cross-continent railroads or waterways, most goods must move by land. But getting a container from one country to another means surviving potholed roads, flooded bridges and even landmines. Along the way, there are officials, policemen and soldiers demanding bribes to allow the goods to continue on their way.

A study by the US department of commerce shows that transporting a tonne of wheat over the 1,000 kilometres from Mombasa in Kenya to Kampala in Uganda costs more than to ship it from Mombasa to Chicago - ten times the distance.

Even where there is demand for better logistics, bureaucracy and inefficiency block it. For instance, Richards Bay on South Africa's east coast is the world's largest dedicated coal terminal, with a capacity to export 90 million tonnes a year.

But Transnet, the state-owned railroad operator, has for years resisted upgrading its network, on which coal mines in the country's interior depend. The result - less than 70 million tonnes a year is exported, costing the country a fortune in lost revenue.

Last year, the country's maize farmers said they suffered losses of 3.3 billion rand (Dh1.56bn) because the country did not have the rail capacity to export surplus crops. Given that South Africa has more rail lines than the rest of Africa combined, the lack of fixed infrastructure becomes even more costly in the rest of the continent.

For the 15 African countries that are landlocked, the obstacles are even more daunting. Basics such as vehicle parts, essential to keep goods moving, become ruinously expensive when they have to be hauled overland after clearing ports in neighbouring countries.

"The cross-border production networks that have been a salient feature of development in other regions, especially East Asia, have yet to materialise in Africa," says Marcelo Giugale, the World Bank's director of economic policy and poverty reduction programmes for Africa.

A study by the African Union (AU) shows that a US$32bn (Dh117.54bn) investment in integrating Africa's road infrastructure could add $250bn in trade in the next 15 years.

Fortunately, this is beginning to happen. The demand for commodities, especially from Asia, is starting to make itself felt in the continent's logistics infrastructure. And international funding agencies are also investing more in roads.

"There is a growth in the interest in logistics, but at the moment we are just seeing the tip of what is hoped to be a much larger iceberg," says Rose Luke, a senior researcher at the Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies in Johannesburg. "In particular we are seeing the private sector playing an active role in leading the upsurge."

Country-to-country roads now amount to about 10,000km and carry about $200bn of goods a year. Ideally, the road network among states should increase by up to 100,000km, says the AU.

Much of the improvement is coming from donor agencies such as the World Bank, IMF and the EU.

And trade partners such as China have also been sponsoring new infrastructure. Beijing is spending upwards of $6bn a year on projects across the continent, much of it paid for through mining and other resource concessions.

But building roads is one thing - it is quite another to maintain them. Donors tend to favour new projects over routine maintenance. The World Bank is urging countries to adopt a user-pays systembased on fuel levies and toll roads to pay for upkeep.

With most Africans living on less than $1 a day, governments are reluctant to try to squeeze more money from a potentially restive population. Even the continent's largest economy, South Africa, is encountering resistance to its plans to extract revenue from motorists.

The country has just spent 17bn rand renewing the highway system around Johannesburg, and was intending to recover the cost through an electronic tag system similar to the one used by Dubai. But a consumer revolt has forced Sanral, the local roads agency, to put the toll rollout on hold. Sanral is now facing bankruptcy unless it can convince motorists to accept the system.

Clearly the old colonial dream of a Cape-to-Cairo route may still be a distant fantasy.

But without better logistical connections among African countries, the continent's roads will remain picturesque threads in a poverty-stricken region.

twitter: Follow our breaking business news and retweet to your followers. Follow us