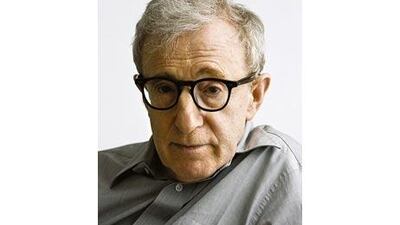

Woody Allen was probably the only man in Britain this summer hoping for bad weather. John Hiscock visits the set of the self-deprecating director making his fourth film based in the English capital and meets a man who has accepted that 'life is meaningless and empty'. Woody Allen squints into the bright sun that is bathing London's Notting Hill in a rare, warm glow and shakes his head in irritation. "I hate sunshine," he mutters. "It should be raining." Then he shrugs philosophically. "But those are the breaks. We'll have to shoot it differently or maybe use a garden hose on the windows." The 73-year-old New Yorker is currently making his fourth film to be set in London, and this time the weather isn't being kind to him. Instead of the grey clouds and rain he loves, he has endured days of sunshine and blue skies. "The sun is a very, very big problem," he says gloomily.

He is taking a brief break from filming a scene for his as-yet-untitled romantic comedy, which stars Josh Brolin, Antonio Banderas, Anthony Hopkins, Naomi Watts and Freida Pinto, the Indian beauty from Slumdog Millionaire. The scene called for Brolin and Pinto to be talking in a restaurant while taking shelter from the rain. The rain is an important part of the story, Allen explains with a straight face: "If you go back through my films you find that it's a tip-off that whenever the boy meets the girl and it's a rain scene, they always mean business. I'm a big rain fan. I think it's beautiful in life and on the screen, so when Josh invites Freida to lunch and she says that it's pouring with rain and he brings an umbrella, you know right away something serious is going to happen. If they had met on a sunny day, it could just be platonic."

As always, he is keeping the plot and title to himself until the film is finished, although he allows: "Josh is playing a very frustrated writer who's having problems with his family and gets into an extramarital relationship, and hopefully it's interesting to people as well as being amusing and also serious. It's a delicate line that I try and hit, and sometimes I can do it and sometimes I can't."

Occasionally he thinks of a title while he is still filming, but he says, "I never title a movie until it's finished because if I look at the film and it's no good I don't like to give it an aggressive title. I'd give it what I call one of my hiding titles - the kind of title that is low key and promises nothing so people are less disappointed by it. But if I feel the film is good, I give it an aggressive, confident title and then hope for the best."

Allen speaks with a deadpan delivery in probably the same style he used many years ago during his days as a stand-up comedian, which makes it difficult to know when he is joking or when he is serious. We are talking in a converted church hall, just around the corner from the restaurant where he is shooting, which he is using to house his staff and the few extras working that day. Listening to him expound his wry views on love, life and filmmaking is one of the better entertainments available in London at the moment.

He is wearing khaki trousers, a floppy sun hat and a blue and white striped shirt and talks in a guilelessly downbeat manner about his lack of hope for the future, his low expectations for his movies and his fear of swine flu. He did not want to shake my hand, although, he insisted: "I'm not one of those crazy people who washes constantly and puts little white gloves on before I touch a doorknob or something. I'm not that crazy, but I do wash my hands for what I know to be a sufficient amount of time." That time, he says, is as long as it takes to sing the lyrics to Happy Birthday twice.

Allen shoots quickly and economically, using small crews and rarely issuing directing instructions. Despite paying his actors minimum rates, he never has any problems getting the cast he wants: most actors would willingly work for him for nothing. "I rely very much on the actors and actresses and I almost never direct them because people like Anthony Hopkins and Naomi Watts are wonderful actors," he says. "They come in and do the part and if I feel I'm not getting exactly what I want, I whisper something to them. I tell them I need them to be a little more sad or a little more energetic. Once in a great while I have to tell them to speak slower or some innocuous thing, but very rarely. I almost never have to speak to them because they know exactly what they're doing and I don't want to interfere with their creativity."

He never writes his screenplays with specific actors in mind, so if someone he casts is not available or drops out - as happened in the current film with Nicole Kidman - he has no problem replacing them. (The British actress Lucy Punch stepped in for Kidman.) The only one he felt was irreplaceable was Diane Keaton, his Annie Hall star and one-time lover. "When I was working with her there was a chemistry that I wouldn't have had with any other actress. No one else could have played Annie Hall or those other characters like she did. Diane was one of a kind and different from everybody else I've ever worked with."

Allen's five years of making films in Europe have coincided with an upturn in his film fortunes. He had a lean spell in the United States, in which he made a series of flops - Small Time Crooks, The Curse Of The Jade Scorpion, Hollywood Ending, Anything Else and Melinda And Melinda. Then the London-set Match Point, a romantic thriller with a surprisingly bleak ending, earned him an Oscar nomination for Best Screenplay, while Vicky Cristina Barcelona, filmed two years ago in Barcelona, won Penélope Cruz a Best Supporting Actress Oscar and a Golden Globe.

He returned to New York for Whatever Works, which he originally wrote more than 30 years ago for the Jewish actor Zero Mostel, who died in 1977. He took the script out of his drawer when the writers' strike loomed and he needed to make a film quickly. The American comedian Larry David, after protesting that he could not act, stepped into the role of the misanthropic intellectual who becomes entangled with the family of a runaway girl he meets and befriends.

London has also proved conducive to his form of filmmaking and, despite the weather problems, he enjoys being in the city where he also filmed Scoop and Cassandra's Dreams. "I just go on the street and shoot. Everyone's very nice here, the crews are first rate, and I usually love the weather, because if I was shooting in New York in the summer, it would be hot and sunny and muggy, whereas in London it should be cool and grey, which is very good for photography. This summer there's been much more sun than I wanted, and it's caused some delays and problems."

One would think that after 50 films, 14 Oscar nominations and two wins, Allen would know exactly what he was doing when it comes to filmmaking. Not a bit of it, he says bluntly. "It doesn't work that way. It's a new thing each time so you never learn anything. Maybe a bit of technique, that's all. I don't know how to do this film because it has completely different problems than all my other films. When I'm making a film I never learn anything that will help me on the next one. So nothing I learnt on my previous films will help me with this one."

He is in London with Soon-Yi, his wife of 12 years who is 35 years his junior and the Korean-born adopted daughter of his former girlfriend Mia Farrow, and their two adopted daughters, Bechet, nine and Manzie, eight, both named after jazz musicians. Before shooting began, they all spent several days watching the tennis at Wimbledon. To fit his new life as a transatlantic filmmaker, he and Soon-Yi sold the town house on New York's Upper East Side, for which they paid US$20 million (Dh73.5 million) in 1999, for $28 million (Dh102 million). Previously, he made a $12 million (Dh44 million) profit on the Fifth Avenue penthouse he had bought in the late 1970s for $600,000 (Dh2.2 million), and he freely admits he has made far more money out of his property deals than he has from his cinematic career.

Allen began his show business career 60 years ago, sending jokes to the columnists Walter Winchell and Earl Wilson. He became a gag writer for such comics as Sid Caesar, Art Carney and Buddy Hackett and made his debut as a standup comedian at New York's Blue Angel in 1960. He was the first guest host to stand in for Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show in 1965. The following year he made his film acting and writing debut with What's New, Pussycat? and had his first play, Don't Drink The Water, produced on Broadway.

Today he is fit, alert and funny, although he is somewhat hard of hearing and leans forward, sometimes cupping his hand against his ear, to hear what is said. For someone who has achieved such iconic status and manages to attract some of the world's biggest stars to work for him for very little, he is refreshingly self-mocking and seems totally free of any ego or self-importance. Despite his two Oscar wins - for Annie Hall and Hannah And Her Sisters - and a slew of awards from around the world, he does not have high expectations for the films he makes nowadays. "When you first start out you're always striving for greatness and perfection, and then after some years reality sets in and you realise that you're not going to get it," he says.

"One of the things that's so fascinating about an art form is that it may be good, mediocre or terrible, but it's not perfect, so when it's over you're constantly impelled to try another one because you suffer from the delusion that you can get perfection. Intellectually, I've given up and I'm happy that the picture is not an embarrassment. I start out thinking it's going to be the greatest thing ever made and when I see what I've done I'm always saying, 'I'll do anything to save this from being an embarrassment.'

"There's not much pleasure in directing. I get up very early in the morning and come to the set and stand around all day while the cinematographer spends three hours lighting the set, then I get 30 seconds to do the scene and then we move on and he lights for another three hours and I get another 30 seconds. It's tedious. I don't do it in order; just a piece here and a piece there and it never looks like anything and you never imagine it's going to come together in a story. The pleasure is when I get home and look at all the footage and sit down and put it together and put in the music and make it look like something."

He may play down his career successes with characteristic self-deprecation, but Allen counts his blessings gratefully. "I've been very lucky in my life and things have worked out well within the limited framework of existence. I'm 73 now and any minute I'm going to get old and infirm and keel over. You know, I'm subject to all the terrible things that happen but within the context of a very grim human existence, I've had a very nice life.

"People have had unspeakably horrible lives, so I've been incredibly lucky and have not had any major health problems and I've had parents with great longevity and I've been in love with some beautiful women who have made enormous contributions to my life and I've got great kids." Then he pauses and thinks for a moment. "But, you know, I could leave this room now and be hit by a falling piano." If he is to be believed - and the answer is possibly not entirely - Allen's view of existence and humankind's place in the universe is a dark and dismal one. "Life is hard, harsh, brutal, short and nasty and there's no hope for us," he states baldly.

"You'll go away thinking I'm pessimistic and cynical, but I'm not. I just feel that our job is to accept the fact that life is meaningless and empty and we're at a random event in a meaningless kind of universe that is eventually going to be gone. I always sound grim when I say this and people always accuse me of being cynical and pessimistic, but I'm not - I'm realistic and I feel those people who sell themselves a bill of goods about how things are going to turn out OK in the end are slightly deluded because things don't turn out OK; they turn out very disappointingly."

Then, without the glimmer of a smile, he asks: "Have I depressed you sufficiently?" Inspite of his gloomy prognosis, it seems the only thing he really does not enjoy about his life is getting older. "Everyone seems to think there's something kind of divine or mellow in getting older, but there's no advantage at all," he says. "Gradually you disintegrate. Your hearing goes, your eyesight goes and you're walking a little slower. You don't suddenly get wise and accept the world for what it is and accept people for what they are and suddenly realise what love is. None of that happens. What happens is your bones ache more." He stands up. "I've got to go back and be bullied by the actors," he says. Around the corner, outside the restaurant, his crew has rigged up a rain machine and water is beating against the windows and on to the pavements, drenching surprised passers-by as well as extras with umbrellas. "Ah, that's better," says Allen with a rare smile. "Rain. Lovely."