This weekend marks one century since the start of what is widely viewed as the first genocide of modern times. Yet the passing of 100 years has mainly served to sharpen the resolve of those on both sides of a white-hot political debate.

Pope Francis set off an international firestorm last week when he referred to the Armenian extermination as “the first genocide of the 20th century”. Technically, the pontiff was incorrect; historians cite the killing of about 100,000 Herero tribespeople in German south-west Africa in 1904 as the first genocide of the 20th century. That mattered little to Turkey, which refused to use the term “genocide” in reference to the First World War-era slaughter in eastern Anatolia, instead using the word “deportations” and citing the wartime suffering of all peoples.

Ankara swiftly recalled its ambassador to the Vatican. Turkish prime minister Ahmet Davutoglu pointed to “an evil gang forming against us”. The head of Turkey’s top religious body said the Vatican had been influenced by “political lobbies and PR firms”. Finally, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan risked the wrath of heaven. “I condemn the pope,” he said.

The narrative clash hits fever pitch this weekend. The Armenian president Serzh Sargsyan is hosting a genocide centennial commemoration in Yerevan, to which he has welcomed an array of international glitterati. The Russian president Vladimir Putin is in town, as is George Clooney, whose wife Amal is representing Armenia in a genocide-denial case against a Turkish politician at the European Court of Human Rights.

Turkey generally honours the iconic First World War Battle of Gallipoli – known locally as Çanakkale, and the first major military triumph for Turkey’s founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk – with events on April 25, marking the 1915 landing of British forces. This year, Erdogan’s government is holding its commemoration on April 24, in honour of a day in 1915 on which nothing of note happened on Gallipoli. In Istanbul, on that day in 1915, police arrested about 240 Armenian notables overnight.

The Great War had descended on the Ottoman Empire like an ink-dark night. The Young Turks, also known as the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) and led by the Three Pashas – Enver, Djemal, and Talat – had run the empire since 1908 and watched it shrink, piece by sizeable piece. After stinging military defeats in the Balkans and the Caucasus, Talat enacted a deportation law in early 1915, calling for the relocation of Armenians from eastern Anatolia.

The true directive – communicated orally to leave no trace, according to The Fall of the Ottomans, a fine new history by Oxford scholar Eugene Rogan – was extermination. After the arrest of prominent Armenians in Istanbul, Ottoman troops and armed gangs conducted bloody massacres across eastern Anatolia. Bandits and soldiers of fortune savaged trains of Armenians marching across the desert. “The purpose of their actions is the total obliteration of the Armenians,” Germany’s vice-consul in eastern Anatolia wrote home in July.

The goal – to ensure Armenians totalled no more than 10 per cent of the population in any area and could never secure statehood in Anatolia – had probably been achieved by the end of the war. By then a group of Armenians had compiled a list of 200 people who engineered the slaughter and launched a plot to kill them all. At the top of the list: Talat Pasha, widely viewed as the architect of the genocide. Soghoman Tehlirian tracked down Talat, living under an assumed name in Berlin, and on March 15, 1921, shot him dead on the street in broad daylight. During the subsequent trial, witnesses testified to the horrors committed against Armenians and the jury acquitted Tehlirian on the second day, citing temporary insanity.

Reading of the trial in Lviv, Poland, a student of linguistics was moved by the Ottoman killings. “I had the certain feeling that the world had to promulgate a law against this form of racially or religiously motivated murder,” Raphael Lemkin wrote in his private notes, according to Ronald Grigor Suny’s new history of the Armenian Genocide, They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else.

Lemkin transferred to law school and, in 1944, after serving as a public prosecutor in Warsaw and teaching law in the United States, wrote a book in which he coined the word genocide, mashing the Greek word for race and the Latin for killing. Four years later, thanks to a moment of post-Holocaust “never-again” consensus and Lemkin’s badgering of delegates, the United Nations passed a landmark convention and genocide became an international crime.

____________________________________________________________

More long read articles from The Review:

■ Acclaimed war photographer Lynsey Addario on kidnaps, death threats and motherhood

■ Forget Lawrence of Arabia, here's the real history of the Middle East and WWI

■ Why Russia should see off China in Central Asia's new great game

■ The puzzling growth of anxiety in the modern age

____________________________________________________________

Seven decades on, the word is less a reference to the most horrific crime known to man than a term politicians shun, an insult hurled against an enemy, a plateau to which victims aspire. For Armenians in particular, Lemkin’s gift has proven something of a poisoned chalice.

“Since the 1960s, Armenian public consciousness has crystallized around ‘genocide’, a word with totemic power,” the scholar Thomas de Waal writes in Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide. “The disputes about the use of the word have become an issue within an issue and have taken on a life of their own.”

Politicians and genocide are rarely on speaking terms. Invoking the most powerful “J’accuse...!” we have tends to elicit official doubt, as no leader wants to acknowledge having allowed the ultimate horror on their watch. “It’s very simple – if it’s genocide you have to do something about it,” Peter Galbraith, former US ambassador to Croatia, said in a recent interview. “This requires changing policies, it may require military action, and it may change strategic relationships.”

Galbraith toured northern Iraq in September 1988 and told Washington that Iraqi president Saddam Hussein’s chemical weapons campaign against the Kurds was intended as a “final solution”. The Reagan administration had other ideas. “They saw an opportunity for American businesses to help rebuild Iraq after the war with Iran,” says Galbraith. “We were unwilling to even cut off the US$700 million [Dh2.5 billion] in aid we gave Iraq every year.”

Avoiding the G-word is often smart politically. Susan Rice, then a rising deputy at the National Security Council, now Obama’s national security adviser, encapsulated the policy conundrum in a 1994 discussion of Rwanda recounted in Samantha Power’s landmark 2002 book, A Problem from Hell. “If we use the word ‘genocide’ and are seen as doing nothing,” Rice wondered, “what will be the impact on the November election?” Hutus went on to slaughter about 800,000 Rwandans, mostly Tutsi, in a 100-day orgy of violence.

Officials often argue that intervention is futile, acting as if the choice is between doing nothing or sending in thousands of troops. Galbraith points to an array of possible responses, from sanctions to air strikes. He says the key is urgency. For those of us familiar with the Holocaust and Rwanda, genocide is relatively easy to imagine. But grasping the scale and intent of killings as they are happening is terribly difficult.

The convention defines the crime as “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such”. There’s no mention of political or social groups, leaving the Stalins of the world free to slaughter dissidents at will. And in the absence of documentation, proving intention becomes a search for clues – the transfer of peoples, mass sterilisation, incidents of slaughter. Consider that Serbia made its first arrests in the Srebrenica case just last month, 20 years after the slaughter of some 8,000 mostly Muslim men and boys.

Smartphones and social media may upend this dynamic. If a reporter or engaged citizen happens to stumble on an atrocity now, an international outcry can emerge within hours, rather than weeks or months. Hashtag campaigns, such as #BringBackOurGirls, in reference to the more than 200 Nigerian schoolgirls kidnapped by Boko Haram last year, can also apply pressure – though provoking successful action is another story.

When northern Iraq’s Yazidi community faced a possible existential threat last summer, Obama needed just four days to respond. ISIL attacked the “infidel” Yazidis on August 3, trapping about 40,000 on Mount Sinjar. Four days later, facing pressure from all variety of media, Obama publicly called ISIL’s attack an act of genocide and launched a mission to drop aid, followed by air strikes.

“This was the fastest response to genocide I think we’ve ever seen,” says Galbraith. “So I think we are getting better.”

Armenians might disagree. When Obama ran for president in 2008 he promised, “as president, I will recognise the Armenian Genocide”. Yet up until this weekend he continued to use the Armenian phrase meaning Great Catastrophe, though the US acknowledges the death of about 1.5 million Armenians. Obama’s hesitance is a result of Ankara’s threat to pull its ambassador and deny US access to military bases should he use the term. Last year when the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee adopted a resolution to “observe the anniversary of the Armenian genocide”, Ankara claimed the wording “distorts history and law”. The International Association of Genocide Scholars unanimously considers the ethnic cleansing of Armenians in eastern Anatolia as genocide, and dozens of US states as well as at least 11 Nato members have officially acknowledged it. The Pope’s use of the G-word and the European Parliament’s recent adoption, by a wide majority, of a resolution urging Turkey to officially recognise the genocide have put added pressure on Obama.

At this point, Ankara’s denialism seems not merely an offence to Armenians, but disingenuous and foolhardy, particularly as the Justice and Development Party (AKP) has made real strides during its dozen years in power. In September 2005, after considerable controversy, Istanbul’s Bilgi University held an unprecedented conference on Ottoman Armenians. The next year, Turkish historians such as Taner Akçam began to acknowledge the genocide in popular books. A year ago, on April 24, Erdogan took an unprecedented step for a Turkish leader, saying he hoped the Armenians who had died between 1915 and 1918 could rest in peace, adding, “we convey our condolences to their grandchildren”.

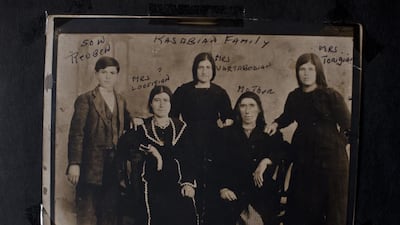

The great-grandparents of the Armenian-American photojournalist Scout Tufankjian fled eastern Anatolia following massacres of Armenians in 1894-95 that were widely seen as a trial run for 1915. Her great-grandfather came from Harput, dubbed “the slaughterhouse province” during the genocide. The 37-year-old visited about 20 countries to capture the Armenian diaspora photos in her new book, There Is Only the Earth, and has a pretty good idea of Armenians’ hopes. “I think an acknowledgement of wrongdoing and a sincere apology would be a good start,” says Tufankjian. “Do I think we’re going to get it? No, I don’t. I have not met any Armenians who think Turkey is going to acknowledge the genocide.”

Denialism may be in the republic’s very DNA. Just as Armenia’s founding is predicated in part on genocide, Turkey’s creation was abetted by its elision. The French historian Ernest Renan famously called forgetting “an essential factor in the creation of a nation”. In founding Turkey, Atatürk sought a clean break – cleansing the state of religion, changing to a Latin alphabet, and altering styles of dress and life. Meanwhile, many CUP officials fought in his nationalist army and later held key positions in the early republic. “For us to actually face our history and accept the reality of Armenian Genocide,” Akçam said in 2013, “means to wrestle with our very identity as Turks.”

Turkish officials also avoid the G-word because its use could trigger requests for compensation, territory and citizenship. The Armenian Revolutionary Federation, or Dashnak Party, continues to make territorial demands, though the Armenian government appears willing to accept Turkey’s existing borders. As for reparations, few genocide scholars believe the UN convention carries retroactive force and could be used to support claims of lost family or dispossessed property.

Thus, an acknowledgement would bring Ankara little shame – the perpetrators were modern Turkey’s Ottoman ancestors, let’s not forget – and little risk of punishment. It would open relations with Armenia and enhance the country’s international reputation. President Obama’s possible use of the G-word might serve to prod Erdogan, who thus far refuses to budge. “It is not possible for Turkey to accept such a crime,” he said last week. “There is no shadow, no stain of genocide on us.”

The stain is on us all; people have sought to eliminate rivals since time immemorial. Humanity’s earthly dominance is probably the result of one of the few successful genocides in history: the killing off of the Neanderthals by Homo sapiens. The Book of Deuteronomy urges of several tribes: “Smite them, and utterly destroy them.” Spanish conquistadors and early Americans wiped out countless Native Americans. Even ancient Athens, that pinnacle of reason, used mass slaughter as a tool of control.

If humanity has learnt anything from the past century it is that we are genocidaires, eminently capable of seeking to eliminate entire peoples. We are also political animals, even Lemkin. A week after the adoption of his beloved Genocide Convention, he opposed the passage of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, fearing it would distract the international community from preventing genocide, the real crime.

His self-interest proved contagious. Cold War foes, Azerbaijanis, Tibetans, Palestinians and Native Americans – all have since made genocide claims, legitimate or not. The Armenians’ genocide obsession has probably undermined their confidence and development; a people defined by victimhood lacks boldness. Many argue that denying genocide encourages future genocides. That may be so. But politicising the word surely leads us away from its extinction. “The ‘G-word’ has become both legalistic and overemotional,” writes de Waal, and “obstructs the understanding of the historical rights and wrongs of the issue as much as it illuminates them.” Similarly, Suny argues, “scholars themselves have paid relatively little attention to truly exploring its causes”.

In the Ottoman case, the end of a half-millennium empire seemed nigh, and the Young Turks felt cornered and desperate. Turkish nationalism surged, with Armenians stretched between the Ottomans and Russians. “The Genocide was neither religiously motivated nor a struggle between two contending nationalisms,” Suny writes, “but rather the pathological response of desperate leaders who sought security against a people they had both constructed as enemies and driven into radical opposition to the regime under which they had lived for centuries.”

In 1915, all the peoples of eastern Anatolia feared the wrath of Ottoman officials. Yet at least 180 of them defied Ottoman orders, including Turks and Kurds who took in Armenian children as their own, according to new research by Turkish journalist Burçin Gerçek. “Back then, people who objected to genocide were sometimes killed,” she said during a recent Istanbul conference on the genocide. She recalled the story of Vehbi Efendi, a former postal director from Diyarbakır, who saved about 200 Armenians, mostly children. “It was almost impossible to protect an Armenian, but still some did it. There were some who defied this atmosphere of fear.”

These defiant few were driven by compassion and a basic sense of right and wrong. They knew to battle an evil that had yet to be named. We have largely failed to follow their lead. “Today, too,” Pope Francis said in his sermon last week, “we are experiencing a sort of genocide created by general and collective indifference.” Indifference to horrific slaughter, he might have explained, and to the word used for selfish ends rather than as Lemkin intended – as a tool to stem humanity’s most base and abominable instinct.

David Lepeska is a freelance writer who contributes to The New York Times, Financial Times and Monocle, and previously served as The National’s Qatar correspondent. He lives in Istanbul.

thereview@thenational.ae