'You're in Bombay, that's incredible, we're having this cosmopolitan conference call, I love it," says Pakistani writer and musician Ali Sethi over the phone from Lahore. A little bit of serendipity – along with a scheduling mix-up – has put us on the same conference call as we wait to interview Indian-American rapper Himanshu Suri (also known as Heems) and British-Pakistani rapper Rizwan Ahmed (Riz MC) about their project Swet Shop Boys and new album Cashmere. After discussing the themes running through the album – racism, the immigrant experience, globalisation's blurring of identities – and the lovely vocal hook Sethi sang on the album highlight Aaja, he says: "I feel like us having this conversation is part of the Cashmere album experience."

I can't help but agree, because at its core, Cashmere is about reaching across borders, across religion and nationality. At a time when politics across the globe is dominated by xenophobia and insularity, Cashmere is about embracing otherness, even if that happens in the form of a coincidental telephone call with someone across the border, discussing music while your governments shout at each other about terrorism and war.

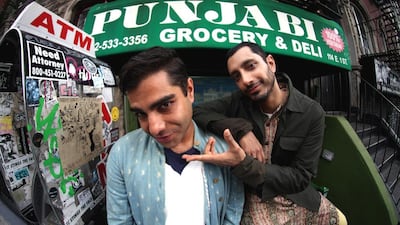

Suri and Ahmed first connected on Twitter. It was 2006 and Ahmed had just released a track called Post 9/11 Blues, which mixed politics and humour in a way that anticipated Suri's work with the comedy-meets-race-commentary group Das Racist. Suri reached out and the two kept in touch. They finally met when Ahmed came down from London to Suri's neighbourhood in Queens, New York, to research for his role in the HBO television drama The Night Of.

“We just kind of occupy similar spaces on different sides of the Atlantic,” says Ahmed.

“I was really drawn to the combination of humour and political insight in his work, and I was trying to tread a similar line, but in a less subtle way.”

In 2014, when Suri was in London for a few months, the two came together to make the Swet Shop Boys EP, a 4 track, 13-minute blast of Bollywood and qawwali (which comes from Sufism) samples, Punjabi rebel poetry and razor-sharp words about the "brown man's burden". Riffing off iconic English electro-pop duo Pet Shop Boys, the name Swet Shop Boys also references the exploitative nature of sweatshops in South Asian countries, where underpaid workers toil to produce cheap consumer goods.

Suri’s languid, NYC-swagger flow acted as the perfect foil for Ahmed’s hyper-dense, rapid-fire bars, while the jagged production wove Indian and Pakistani influences into a more universal tapestry that derived from American hip-hop and UK grime.

Earlier this year, the two got back together, this time with English electronic polymath Redinho as producer, to create Cashmere, a debut album that fulfils all the promise of the EP and then some.

The incendiary opener T5 kicks things off with Suri and Ahmed trading rhymes about racial profiling over a jagged bed of distorted shehnais (a north Indian wood instrument similar to the oboe), samples of sniffer-dog growls and 808 drum machine thumps. Suri rhymes "mashallah" with "martial law" and sings the tongue-in-cheek hook: "Oh no, we're in trouble/TSA always wanna burst my bubble/Always get a random check when I rock the stubble". Meanwhile, Ahmed calls out "apolitical" rappers ("We're militant, you're on a Milli Vanilli vibe") and references The Iliad to make a case for refugees ("Fled Turkey and he just founded Rome/What if he had drowned in a boat?").

Shottin continues with the theme of racial profiling and Islamophobic policing. It's a track where Heems role-plays as a drug dealer who gets caught and finds Islam in jail, only to come out and find that the Feds are even more interested in him now that he's Muslim. (Ahmed wrote a well-received long read in The Guardian recently about his experiences with airport security checks.) It also ties together 1990s hip-hop with the record's South Asian cultural inheritance, such as when Suri gives a nod to a track by South Jamaica's Lost Boyz, which discusses fatal confrontations with the police, along with samples from Pakistani qawwali singer Aziz Mian and hip-hop tropes with references to the Sikh festival of Vaisakhi and the Hindu festival of Rakhi.

This code-switching and intertwining of qawwali and 90s hip-hop, South London slang and Punjabi colloquialisms, is one of the most exciting aspects of the record. Suri and Ahmed, helped by Redinho (who not only researched South Asian instruments and musical traditions extensively, but even played synthesised versions of some of the instruments instead of just sampling) claim both UK and US pop culture and their South Asian heritage as their own. They almost challenge you to try to separate these different strands.

“If [Pakistani qawwali singer] Aziz Mian was an MC who was from Brighton Beach instead of Pakistan and was doing rap instead of qawwali, what would his tape sound like?” says Suri.

The same thread runs through the entrapment saga Phone Tap and the hilarious stunting on No Fly List, with its self-deprecating hook "I'm so fly ... / But I'm on a no-fly list." Meanwhile, Zayn Malik, named after the former One Direction star with Pakistani ancestry, explores the idea of South Asian representation in the media and the importance of having aspirational role models who look like you. "I'd like to hope that we're laying the new footprints in the snow that people can follow and try to add South Asian visibility to the cultural landscape," says Ahmed.

It's not all political though, there's enough humour and beats to keep everyone entertained. Set over a synth-sitar riff, Tiger Hologram is a funny take on the two enjoying a night on the town. Swish Swish is a typical Heems tune, with South Asian in-jokes about being "young Akbar in the Chevy" and his "two gold chains, one from mama, one from grandma".

Mughal references resurface on Ahmed's song Half Moghul Half Mowgli, where he talks about balancing dual identities and does his own take on fan-letter responses, as well as the final track about self-love and dealing with cultural appropriation ("Used to call me curry, now they cook it in the kitchen"), which takes its name from Mughal emperor's Akbar's short-lived syncretic religion Din-e ilahi. "It's about expressing cross-communal solidarity and also tapping into a heritage and a narrative of empowerment," explains Ahmed.

It's hard to find a flaw with Cashmere, which mixes together the personal, the political and the universal in good measure, with a generous helping of good-natured subversion and humour. By turning a mirror on themselves and their experiences, they've constructed a new cultural identity that is both specific and universal.

Or as Ahmed puts it: “It’s about celebrating people who don’t fit into neat binaries that are imposed on us in this increasingly globalised world – black or white, eastern or western, Hindu or Muslim, Indian or Pakistani. These are all oversimplifications that don’t reflect the complexity of our realities. So this album is a celebration of the mongrel.”

Bhanuj Kappal is a freelance journalist based in Mumbai who writes about music, protest culture and politics.