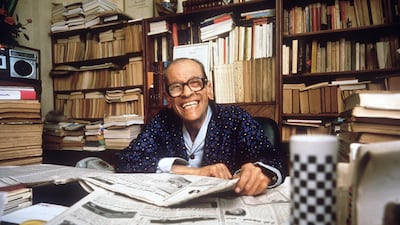

Egypt celebrates the 108th anniversary of the birth of its most famous novelist, Naguib Mahfouz, today. In past years, the American University in Cairo Press has given out a Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature. But this year, the publishing house will not present the prize. Publisher Nigel Fletcher-Jones says it is "scrutinising" the award's structure and plans to re-launch a new version in 2020.

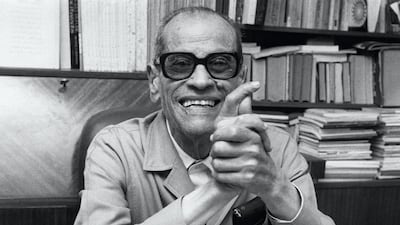

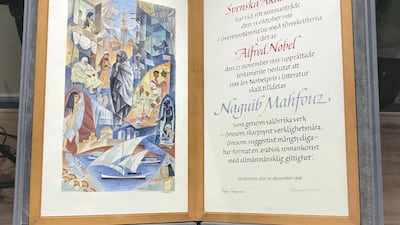

That makes it a good year to reassess Mahfouz's oeuvre – especially what's available in translation. It was 30 years ago that Naguib Mahfouz, who was born in 1919 and died in 2006, achieved sudden global fame when he became Arabic literature's only Nobel Prize winner. The Swedish academy commended the author for his great mid-century novels: Midaq Alley (1947), The Cairo Trilogy (1956-1957), Children of the Alley (1959), and Adrift on the Nile (1966). But Mahfouz has written much more.

A tremendously disciplined author, Mahfouz began publishing essays as a teenage philosophy student. Mahfouz's entire literary career spanned 70 years and produced tens of novels and hundreds of short stories, as well as plays, movie scripts and essays. Every single one of his 35 novels has now been published in English, and in the past decade, we've even seen collections of his newspaper essays in translation. So, if we were to give Mahfouz a new look, where would we begin? We could start with the freshest translations. This summer, Saqi Books published a collection of newly discovered texts, titled The Quarter. These short works, apparently written in the early 1990s, were discovered in September last year by journalist Mohamed Shoair, who also found an early autobiography. But while the short Sufi-esque works in The Quarter are interesting, they are not Mahfouz's most powerful.

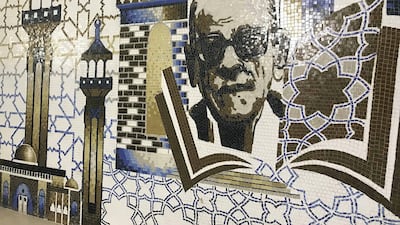

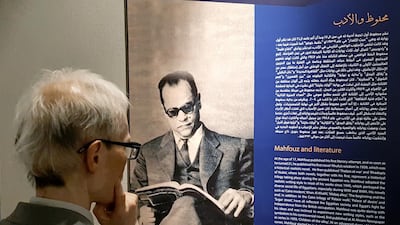

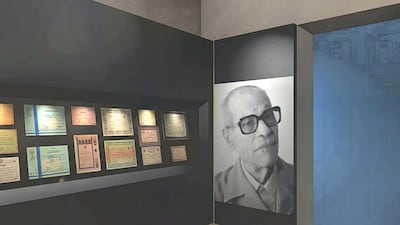

Another place to start could be with new Egyptian novels that write in a Mahfouzian tradition. Nael Eltoukhy's Women of Karantina (2013) was initially conceived as a response to The Cairo Trilogy. Ibrahim Farghali's Sons of Gabalawi (2009) is an echo and response to Children of the Alley. Or, even better, we could start with a fun, accessible book about Mahfouz. Unfortunately, one hasn't yet been translated into English. In Arabic, there's Shoair's Children of the Alley: The Story of the Forbidden Novel, told with the writer's flair for evocative detail. Those in Cairo can also visit the newly opened Naguib Mahfouz Museum.

But won’t any Mahfouz novel do?

If we're starting afresh with Mahfouz's novels, some are certainly better than others. His Love in the Rain is hardly as memorable as The Cairo Trilogy. What's more, the translations have been uneven. When Mahfouz's work first began to appear in English, there wasn't a strong cadre of literary translators. In the 2000 essay The Cruelty of Memory, Edward Said looked at 11 Mahfouz translations and found that "in English he sounds like each of his translators, most of whom (with one or two exceptions) are not stylists and, I am sorry to say, appear not to have completely understood what he is really about."

Like a number of Mahfouz's mid-century works, The Cairo Trilogy had a rough road to English. For years, Trilogy co-translator William Hutchins, says, a translation of the work "had been sitting in a closet at the AUC Press." Then, in the mid-1980s, this manuscript was nudged into the light. That's when "someone there finally decided that it was not publishable [in its condition at the time], for whatever reason," Hutchins says. The translation was given to him for editing.

"At the time I did not realise quite how difficult Bayn Al Qasrayn is to translate, only how important it is," Hutchins says. "So I agreed to help, rather naively, I admit. After only a few lines of trying to edit the extant translation, I decided that I would need to create a fresh translation." This version of the Trilogy received wide release after Mahfouz's Nobel Prize, and it has charmed thousands of readers. But it is also something of a patchwork effort.

A number of other Mahfouz translations, says Denys-Johnson Davies, were done in pieces. They were originally "undertaken by a native speaker of Arabic," after which they were "handed over to one or more persons who would 'iron out' the initial text." Johnson-Davies wrote, in his Memories in Translation: "A look, for instance, at the title page of the Mahfouz novel Miramar (1967) reveals no less than four names have participated in its translation– which is not to say that the end result is not perfectly acceptable."

Click through to see Cairo's Naguib Mahfouz Museum

It's hard to know what exactly Johnson-Davies meant by "perfectly acceptable," but the novel also deserves a new, 21-century translation, although this may be complicated by the current legal dispute over licensing agreements between Mahfouz's daughter and AUC Press.

The mid-century novels mentioned by the Nobel committee are Mahfouz's best-known works. But to give Mahfouz a fresh look, we could also start with these innovative works he was publishing in the 1980s, before he was near-fatally stabbed in 1994. They give us a broader understanding of a novelist often compared to Charles Dickens or Honore de Balzac, but who was also a relentless experimenter.

Essential reads

‘Midaq Alley’ (1947) Re-translated by Humphrey Davies in 2011

The alley is a key social unit in Mahfouz’s oeuvre. This novel was praised by the Nobel academy. It reflects Mahfouz’s sharp portraiture.

‘Adrift on the Nile’ (1966) Translated by Frances Liardet in 1993

This dialogue-focused novella centres on drug use, an accidental crime, and a nihilist, unmoored drift down Egypt’s central river.

‘The Journey of Ibn Fattouma’ (1983) Translated by Denys Johnson-Davies in 1992

Here, Mahfouz’s work moves toward the Sufi-esque political allegory of later his books, following a man’s sometimes surreal journey towards “Gebel”.

‘The Day the Leader Was Killed’ (1985) Translated by Malak Hashem in 1997

Another novella, this is a polyphonic domestic tale that leads up to the day Egypt’s former president Anwar Sadat was assassinated.

Morning and Evening Talk (1987) Translated by Cristina Phillips in 2007

A brilliant and experimental collection of 67 biographical shorts, arranged alphabetically, depicting three Egyptian families over two centuries.