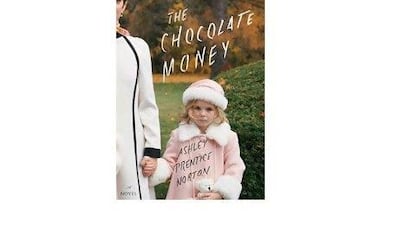

Bad mothers. They are the dramatic conflict for everything from Medea to Carrie to Psycho, not to mention any fairy tale worth its salt. In her debut novel The Chocolate Money, Ashley Prentice Norton gives us a mother who makes Snow White's stepmother look like a Girl Scout, and who treats her daughter with such callous disregard that were it not for Norton's deft touch, the novel would be unreadable.

As it is, however, The Chocolate Money creates an indelible portrait of a daughter's journey to adulthood across the minefield of her mother's destructive narcissism. The novel's title may suggest a light-hearted romp through worlds of candy-coated wealth, but don't be fooled: this is not "chick-lit". It is a bleakly witty examination of how excessive wealth, when untethered from responsibility or obligation, can destroy individual lives and relationships.

Bettina Ballentyne, the novel's narrator, is the daughter of the fabulous Babs, heiress to the Ballentyne chocolate fortune - the "chocolate money" of the title. Babs' money lifts her out of the realm of mere wealth and into a place where friends play a game called "speed shopping", the goal of which is to see who can go into a store such as Gucci and spend US$10,000 (Dh37,000) the fastest. The only rule is that the shoppers have to buy items they will actually use.

Bettina, who is 10 when the novel opens, describes her mother's behaviour in the non-judgemental tones of a child; she observes rather than evaluates. Sometimes, as when Bettina has to explain to her teacher at school that she does not, in fact, have a father and thus cannot invite him to the "Daddy's breakfast", her childish perspective creates satirical humour. But at other points, the reader cringes. We see, long before Bettina does, the psychic damage that Babs' behaviour inflicts on Bettina, who accepts her mother's casual cruelties. For Babs, Bettina is "a match that won't strike". The chocolate money seems to have damaged Babs in some crucial way; she cannot see people as anything other than objects to be moved around or disposed of at her whim.

Babs always needs to be in control, and when her control is thwarted, her rage - and her need for retribution - seems almost limitless. Her daughter, unfortunately, is no exception: Bettina is sometimes an accessory, sometimes an audience and frequently the scapegoat. So, for instance, when Babs' married lover ends their affair, Bettina suffers the brunt of Babs' rage and becomes the unwitting tool of Babs' attempts at revenge. It's never clear if Babs' fury at being jilted comes from the fact that she actually loved the man or if she just hates that he left her first. Bettina never understands her mother's feelings, so Babs' actions around the affair become simply another instance of Babs' opacity.

And while it is true that children rarely understand their parents' emotional lives, it is one of the novel's weak points that the reader doesn't understand Babs either. We are told that Babs' parents died in a horrific boating accident but is it that, plus her massive fortune, that account for her being such a manipulative, narcissistic woman? Babs is fascinating but she is all surface; we only ever see her icy hauteur, as when she says to Bettina: "Since when have I been lumped into the category of parents? What, I want to know, is in it for me?"

Babs lives in defiance of the rules, which makes her both dangerous and attractive. And Bettina, as she grows up, oscillates between being critical of her mother's behaviour and yearning for her approval.

So, for instance, when Bettina arrives as a first-year student at a boarding school in the eastern United States, she scoffs at the ordinary families helping their children get settled - and wishes that Babs were with her, adding homey touches. Bettina's ambivalence about her mother suggests the strength of the parent-child connection: no matter how horrific the mother, the child doesn't ever, fully, want to escape her clutches.

Bettina attends the fictional Cardiss boarding school, which is a pitch-perfect representation of the "preppy" world of the north-eastern United States. From the poseur student poet to the blonde queen bee, from the quirky, earnest faculty to the mannish women's field hockey coach, Norton perfectly renders the hermetically sealed world of the boarding school, where traditions and rules can be violated with abandon - as long as you don't get caught - and where knowing the unspoken codes of behaviour seems to matter more than grades.

Unlike virtually everyone else in her building, Bettina shows up at Cardiss alone, just returned from a summer in France. All her clothes fit in one Louis Vuitton duffel and she has no little knick-knacks with which to personalise her room. Her room-mate's parents decide that Bettina must be a scholarship student and give her US$10 (Dh37) to help her "settle in", which puts Bettina in a hideous dilemma: reject the gift and tell the truth about the chocolate money, or accept the gift and keep the fortune a secret. She opts for secrecy, and when her roommate, Holly, asks if she is related to the Ballentynes, Bettina says no. After all, is there a casual way to mention that one day you're going to be worth hundreds of millions of dollars?

Bettina longs to be part of the crowd at Cardiss but she has no idea how to create a circle of friends. She's never had a friend her own age and the things her dorm-mates talk about seem completely foreign: she's never been to a prom, has no siblings, never had a boyfriend, never driven a car. Whatever information Babs has passed along to her is as useless at Cardiss as the contents of the care package she sends to Bettina. It contains clothes that are too fancy and piles of contraband: alcohol, condoms and cigarettes. Initially, Bettina is delighted at the gift because it meant that Babs is "thinking of me. Misses me." Only later does she wonder if the box weren't intended more as sabotage than affection.

Lonely and uncertain, Bettina does what unhappy teenage girls have always done: she seeks comfort in the arms of Cardiss's "bad boy", a relationship that echoes Babs' emotionless dealings with men. In these encounters, however, Bettina discovers in herself a masochistic need for pain, as if to physicalise the psychic wounds that Babs caused. Ironically, Bettina's one attempt at a relationship with a "nice boy" places her at the centre of a scandal that even Babs can't fix. Bettina can't win: when she tries to conform to Cardiss's rules, Babs calls her a coward; when she is asked to leave the school because she violated the rules, Babs calls her a fool.

There are two major plot twists in the chapter following Bettina's expulsion from Cardiss, one of which an astute reader will see coming and the other of which is horrifying, shocking and wickedly funny. These developments conclude the story of Bettina's youth but the novel ends with a coda, in which Bettina is now 26 and living in New York.

She has used a fraction of the chocolate money to buy herself an apartment at a fancy address but, for the most part, she tries to ignore her fortune so that she can lead a "normal life, if such a thing exists".

In the final pages of the book, someone from Bettina's past asks her if she's afraid she will end up like her mother. Bettina says "even though this is my greatest fear, I say confidently 'you can't turn into people … even if I make all the same mistakes … I will still be me'."

Unlike her mother, Bettina has a job (gained with no family string-pulling), so perhaps she will be her own person and avoid joining "the tribe of the smug few who do nothing but shop and party". While Bettina's is an extreme case, this intelligent novel reminds us that we all confront a version of this question: how do we make our peace with our parents' mistakes and move on to create our own lives?

Deborah Lindsay Williams is a professor of literature at NYU Abu Dhabi.