Beirut Noir

Iman Humaydan (ed)

Akashic Books

Dh53

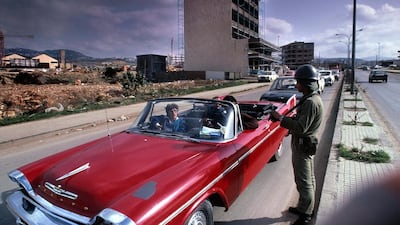

The Lebanese civil war is over, but the warlords are no less intimidating and powerful.

Abbas Beydoun's The Death of Adil Uliyyan, one of 15 short stories in Beirut Noir, has ageing former sniper Uliyyan holed up in his luxurious cliffside villa, on the verge of death and wanting to make one last confession. An old comrade is the unwitting recipient of Uliyyan's confession and is forced to reckon with the brutal logic of a war that he would rather forget.

Beydoun’s story is exactly what one would want from a noir take on Beirut – sharp, unrelenting and delivering no-nonsense truths. “As soon as killing starts, as soon as human life becomes cheap, then everything is allowed,” he writes.

Beirut Noir is the newest title in Akashic Books' popular noir series. Up to 75 cities have been featured – from Zagreb to Havana – and Beirut is undoubtedly a locale with sufficient brooding atmosphere to sustain its own noir imprint.

Edited by Lebanese novelist Iman Humaydan, Beirut Noir is not always what you would expect. Not every story features a detective with a troubled past or a femme fatale eager to seduce, and most steer clear of the tired clichés that seem to pursue Beirut.

The Lebanese authors featured in the collection draw from a much broader palette of Beirut life, and, true to the genre, they tap into their city’s dark past and uncertain present. Some stories are absurd and humorous, but almost all are haunted in some way by a nagging memory, a war, a death.

Poet Bana Beydoun's Pizza Delivery is a surreal trip through Beirut bars and parks, while the city's south is bombarded by Israel. Maya is a woman lost in her thoughts, slowly drifting from everyday reality toward a more hospitable, dreamlike world.

“Once she’d read that sometimes your imagination can recreate reality according to your own image of it,” writes Beydoun. Maya’s night takes a weird turn when she is pursued by a “hunchbacked man” who has a message for her.

Beydoun's story hints at the absurd bent to come in many of Beirut Noir's stories, like novelist Rawi Hage's Bird Nation, a caustic satirical treatise on the paradoxes of Lebanese life, starting with birds and bread and ending with the political class's affinity for tinted windows and Hummers.

Perhaps it’s not noir, but it’s enjoyable: “The whole city drove veiled in glass and metal. People were no longer able to assess wealth, honor and danger. All of a sudden, the city felt equal and the people lost their sense of self-worth.”

For a noir collection, the stories are surprisingly diverse, but sometimes, these feats of storytelling are not enough to keep one engrossed.

The Amazin' Sardine, aka Mazen Zahreddine, a Lebanese Vancouver-based performer, tests the limits of bawdiness with Dirty Teeth as his hedonist protagonist delves into Beirut's nightlife, narrating his escapades in a fusion of Arabic slang and Clockwork Orange-speak.

“Monot Street, baby boys. It’s three letters away from monotony, that part is true. But yalla, drunk as I was, I did not feel any difference,” observes the narrator.

Other stories feel too unhinged. Characters are disconnected from reality with little explanation as to why. Narrators are absorbed in their own private miseries but with little pay-off for the reader.

Beirut is a city that ties some firmly to the ground, while others float in and out of reality. So much disorientation at once is a bit overwhelming in the collection, making the characters that seek resolution in action a welcome respite.

Bachir Hilal's Rupture is one such story. Comrade George is assigned to the security detail of a bourgeois doctor's wife – a French femme fatale. As a loyal member of the Communist party, George is conflicted. The woman represents everything he is supposed to hate but in her company he finds himself "searching for something outside the party in passion, in madness, in silence".

Hilal, who moved to France at the onset of the Lebanese civil war, passed away this year before the publication of Beirut Noir. His story is an elegiac take on how it is hard to hold on to one's humanity in war.

“I should come up with a dream that would take me away every night,” muses the young protagonist. The reader is uncertain if he is ever able to escape the war.

Akashic is set to release more Middle East noir titles in the future, including Baghdad Noir, edited by Iraqi writer Samuel Shimon. If Beirut Noir is a hint of what's to come, Baghdad Noir will upend our old notions of the genre.

Leah Caldwell writes for Alef Magazine, the Los Angeles Review of Books and the Texas Observer.