The beating heart of the Beirut Art Fair this year is an exhibition that is at once tragic and desolate, inspiring and uplifting. Ourouba: The Eye of Lebanon, curated by Rose Issa, also a London-based writer, seeks to answer a complex question: what does it mean to be Arab today?

Featuring work by more than 40 prominent artists from the Arab world created in the past 10 years, the exhibition captures the anxieties, interests and obsessions of artists interrogating their histories, cultures and identities. "I was interested in seeing, since 2011, with all this chaos and all the uprisings in the Arab world, what were artists producing and in what way did it affect the collectors? What were the concerns of the last 10 years, artistically and in terms of collecting?" Issa says.

The non-profit show includes paintings, sculptures, photographs, video works and installations, and occupies 400 square metres, a significant portion of the fairground.

The pieces are all on loan from private collectors throughout Lebanon, giving the show a double focus – not only does it consist of artworks that are significant to Issa, but those that have been successful on the market.

"Some Arab artists produce wonderful work that is never acquired by anyone, or that is acquired by westerners," explains Issa. "I wanted to see what the Arabs themselves collect … what kind of eye do we have on our own culture?"

Many of the artists are from Lebanon, but Issa has also included works by Syrian, Iraqi, Palestinian, north African, Armenian and Saudi artists. More than 40 are represented, including some of the region's best-known figures, among them Ayman Baalbaki, Rabih Mroué – Walid Raad, Mona Hatoum, Marwan (Kassab-Bachi), Adel Abidin, Hanaa Malallah, Ahmed Matar and Mounir Fatmi.

Through their work, Issa tries to uncover answers to the questions surrounding being an Arab. "How do we think about our identity? In what way are we original? What makes our originality aesthetically, conceptually, socio-politically, nationally?"

As one might expect, many of the works deal with violence, conflict and upheaval. "There is a lot of destruction, whether in the faces or in the buildings," says Issa. "Take this new generation – Serwan Baran, Ayman Baalbaki, Tagreed Darghouth. Their work moved me. They were born with the war. They only know war. Even after the ceasefire, they received 1.5 million Syrian refugees in Lebanon who have their stories to tell."

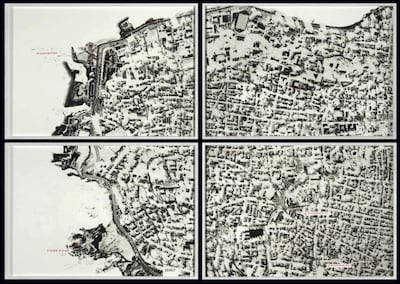

One of Baalbaki's paintings captures the historic Barakat Building – now open for the first time as Beit Beirut – during mid-renovation, covered with scaffolding. Behind this cage-like grid of iron bars, the building looks as it did in the wake of the Lebanese Civil War, its beautiful façade pitted and scarred, its windows black holes.

Darghouth's work includes paintings of missiles, their blunt, smooth curves deceptively harmless, almost organic in appearance. Lebanese artist Katya Traboulsi, meanwhile, is showcasing a brass sculpture entitled Perpetual Identities – Palestine. It consists of hundreds of keys – resembling those still worn by many Palestinian refugees in Lebanon as links to homes long lost to occupiers – welded together in the shape of a missile that sits atop an ammunition chest.

Syrian artist Youssef Abdelke captures a woman in black in sorrow before a portrait of her martyred son, while Hatoum and Mohamad Said Baalbaki have produced sculptures based on the Martyrs' Monument.

Yet many of the works in Ourouba are not about conflict or loss. Issa's nuanced selection reflects on aspects of Arab identity that have nothing to do with war. Lebanese artist Nabil Nahas is showing two paintings capturing cedar trees, with which he fell in love with after returning to Lebanon following decades of absence.

"The symbol of the cedars of Lebanon is tied to the notion of identity. To what extent are we promoting it or defending it, sticking to it or not?" Issa says. "The notion of identity was very important for me because in these times the word 'Arab' or 'Islam' has become such a pejorative thing."

Just as Issa has chosen to include two sculptures based on the Martyr's Monument, she pairs Nahas's paintings with a small sculpture by Ginane Makki Bacho, a cedar made using fragments of shrapnel from the civil war. These unexpected but perceptive pairings of artworks that might be familiar but unlinked in visitors' minds gives the show an added element of strength, facilitating new readings, cross-connections and shared preoccupations between artists working in different places and times.

Violence aside, Issa says that the common theme that struck her was a shared love of beauty. "How do we fight and how to do we survive? It is with love and beauty and celebrating life," she says. "Wars have always existed and horrible things have happened to everybody in every country … but people are still surviving and producing beautiful artwork.

"Who remembers ancient Greece except through the artwork that they left us? The writing, the sculptures, the paintings – nothing remains except the art."

Beirut Art Fair runs at the Beirut International Exhibition and Leisure Centre, Lebanon, until Sunday

_______________

Read more:

Art exhibitions in the UAE: what to see now the new season is here

Lebanon's movement to remember

_______________