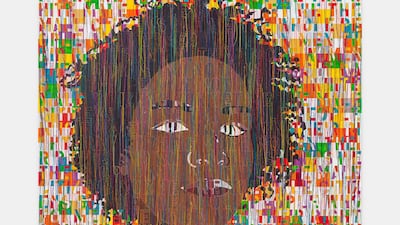

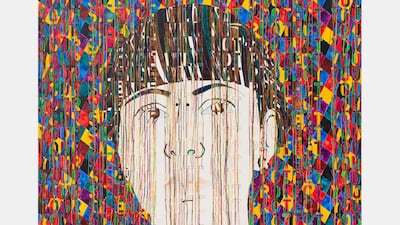

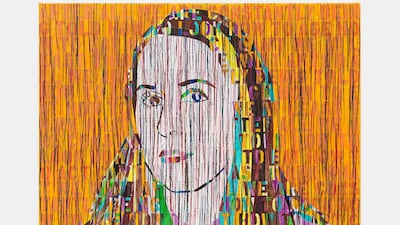

In Ghada Amer's paintings, threads behave like coloured rivers, abstraction obscures figuration and unknown women proliferate. However, for the first time, familiar faces are appearing in Amer's work. Although the Egyptian artist, who lives and works in New York, calls the female figures she sources from popular culture – often men's magazines – her "friends", she has been looking to her own environment for her latest series.

Her assistant, a cousin, a fellow yoga student, and her sister, are all featured in a series called Women I Know. "I drew the faces based on photos I took and then found the right sentence with which to compose each portrait," Amer says. "Although I began this work in 2014, I was diagnosed with breast cancer just before the pandemic hit. I was home for a year and I had the strength to focus. I could think about how to continue the series," she explains.

“In the past, women were only allowed to do portraits. They couldn’t paint the church, wars or any of the important stuff,” she says. This is a familiar refrain, and Amer has consistently incorporated embroidery and feminised expression in her work as a critique of male-dominated genres in art history, where painting reigns supreme.

Known for her serial renderings of women's bodies in works, Amer refers to the hyper-masculine codes embedded in Abstract Expressionism (think of Jackson Pollock's drip paintings inspired by the act of his father urinating outdoors in patterns). Her candy-coloured evocations of female figures in provocative poses constituted by skeins of thread are affixed by transparent gel and, at times, supplemented with paint. "In some canvases, I add paint because I needed more proximity to painting," she says. "Now that I can paint, I also use it as a material."

Amer has often told the story of when she was studying for her master's in fine arts at Villa Arson in Nice, France. There was only one professor of painting, who didn't accept her into his class. This sparked the beginnings of her inquiry into painting with thread.

“I mastered a series depicting women with thread and needle,” she says. “It became a way for me to paint, a technique. I wanted images that represented a separation from sewing … The essence of the work is about women having a place in painting. It’s not just a reference to women’s work.”

Amer's dangling threads are like sketches and lines before they commit to form; they read as shadowy outlines that bleed into bodies that blur and multiply. "I've always been interested in the female form, especially in live drawings during art school. In the Middle East, women are always appraising other women. It's different from the male gaze, where men often isolate and focus on parts of the body."

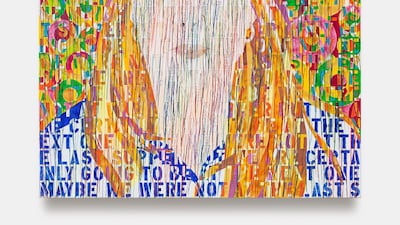

Her latest body of work integrates different strands of her practice: text and figuration. Amer superimposes phrases on the portraits, such as "Your silence will not protect you" by feminist poet Audre Lorde.

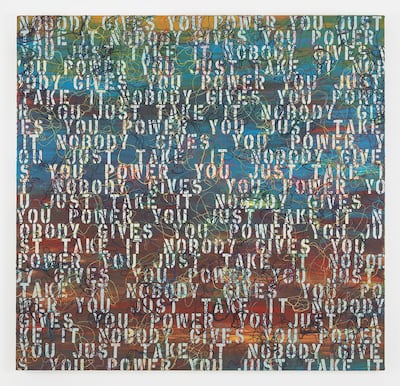

"So many things have already been said. These are not new thoughts," says Amer. "My practice was influenced by the powerful statements of [American artists] Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger. When I read, I always take note of what inspires me, and it's these quotations that remain."

Incorporating writing is not unusual in Amer’s practice – her materiality has often been extended to language – but this is the first time both text and figure occupy equal space in her work.

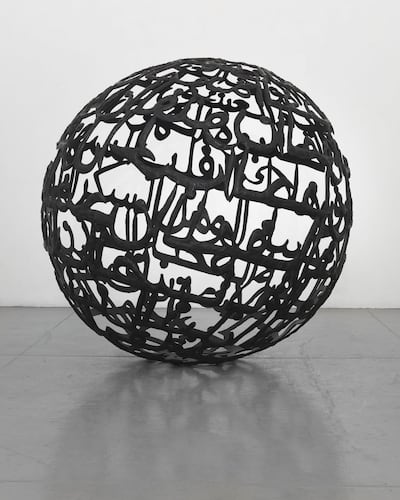

“In Arabic culture, words are another form of painting – calligraphy is not merely a decorative form – so I don’t see the difference between words and figures. It’s not a strict dichotomy.”

In 2001, she created a 70-metre-long public installation in Barcelona stating: "Today 70 per cent of the poor in the world are women" in Spanish. Her Encyclopedia of Pleasure comprises 57 canvas boxes inscribed with embroidered translations of a medieval Arabic text on spiritual and physical fulfilment in men and women, written by Ali ibn Nasr Al Katib. Amer's The Words I Love the Most (2010) is a hollow lattice-like sphere adorned with 100 Arabic expressions for love. In Sunset with Words (2013), a collaboration with American-Iranian artist Reza Farkhondeh, she stencilled: "Nobody gives you power you just take it" across a hazy degradation of rainbow colours. In another 2015 piece, Sindy in Pink, "We are the granddaughters of witches you cannot burn" can be read.

"I turned towards writing very early in my career, and like the images I source, the words are always found texts. I want to appropriate and remember."

The connection between words and images is analogous to the relationship between painting and sculpture in Amer’s work. Although her embroidered paintings and ceramic sculptures are separate as works, sometimes they merge into one configuration. Her art seems to explicitly comment on the levels of intimacy implicated in states of longing and language.

In one of her earlier series, Cinq femmes au travail (1991), showing women involved in domestic tasks, she depicted herself. "I am the fifth woman in the series, embroidering the others." In Women I Know, her self-portrait is the only black-and-white image, with words that are hard to make out. For this, she selected a controversial definition of feminism by televangelist and political commentator Pat Robinson: "Feminism is a socialist, anti-family political movement that encourages women to leave their husbands, kill their children, practise witchcraft, destroy capitalism and become lesbians."

In this vein of definitions, Amer has recently created a site-specific garden sculpture in Sunnylands, California, for Desert X, where she uses desert plants to spell out seven qualities of women that she identified through a poll. This installation, Women's Qualities, was first conceptualised for the Metropolitan Museum in Busan, South Korea, where descriptors such as "submissive" and "long-lashed" came up. She also did the project last year at the Rockefeller Centre in New York by sampling a wide range of people, from Mexican workers in her art studio to friends and family from Egypt.

The Desert X version includes qualities mentioned across the East and West coast: "resilient, beautiful, strong". But Amer has gone completely abstract in her public art, too, with earlier installations such as Cactus Painting (1998), made out of receding rectangles of 16,000 cacti, or with more recent ceramic sculptures such as The Black Knot (2014) and Yellow Lines (2015).

At the moment, Amer is working on new Women I Know works for her first solo exhibition in September, at Marianne Boesky Gallery in New York, where she will include more family members. Further pushing the relationship between text and image, her literary fragments are not easily visible in recent works, which separate words across the portraits. Employing her characteristic visual language, Amer brings certain elements into focus, while fading others from view.