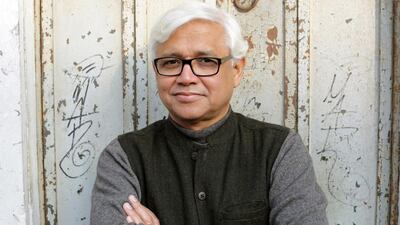

Anyone planning to see Amitav Ghosh, either at the Sharjah International Book Fair on November 13 or at tomorrow’s, November 7 discussion at New York University Abu Dhabi Institute, should consider themselves lucky. Admired the world over as a novelist, essayist, Tweeter and blogger, Ghosh is in demand everywhere he goes.

Nevertheless, public performance is not the natural medium for an author who prefers the written word to the spoken one and solitude to crowds.

“I spend a lot of time in seclusion. Writing is very demanding. You can’t write if you are in a constant uproar. Especially in the past 10 years while I was writing the Ibis trilogy, I did very little else. I live, I would say, quite reclusively. I actually avoid literary festivals.”

Ghosh arrived in Abu Dhabi last month to take up a post as writer-in-residence at NYUADI. When I ask what he has been up to, he sounds blissfully relaxed. “Not much,” he replies in his elegant drawl, “except reading and being in the library really. That’s the whole point of it. Trying to finish some essays.”

This portrait of present ease belies a typically hectic work schedule. Last month, Ghosh concluded his monumental Ibis trilogy, which deserves to be remembered as one of the finest literary achievements of the early 21st century. A vibrant account of the Opium Wars, it begins with the idiosyncratic cast of Sea of Poppies, which was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, and continued with the hallucinatory River of Smoke. The final part, Flood of Fire, is due for publication in the spring.

Nevertheless, it is two earlier books with strong Middle Eastern associations that form the basis of this week's events. At Sharjah he revisits his first novel, The Circle of Reason, which follows Alu, a master weaver, on his peripatetic wanderings from Mumbai to the Arabian Gulf. At the NYUADI discussion, he'll explore his non-fiction book In an Antique Land – in particular the chapters about the Cairo Genizah, documents that detail the lives of Jewish traders.

Other sections of In an Antique Land narrate Ghosh's first encounters with the Middle East. In 1980, he travelled to the Egyptian village of Lataifa where he lived, wrote and undertook research for a PhD in anthropology. "I already saw myself as one of those writers who sees the world. Egypt was halfway to India. There were similarities of historical experience and a sense of solidarity because of the Non-Aligned Movement."

When I ask how visiting the UAE 35 years later compares to that formative experience, Ghosh’s response introduces the dominant theme of our conversation: crisis. “This is just about the only part of the Middle East that is not convulsed.

“I have a very long relationship with the Middle East. I speak Arabic. I think the Middle East is going through a moment of trauma, an absolutely critical moment in its history.”

Which is, I prompt? “What the Middle East and Syria represent is the utter folly of the powers-that-be in the world, their complete ignorance. What can you call it but madness to be doing what they have been doing over the past 15 years?”

We begin by discussing the rise of the Islamist extremist group ISIL in Syria and Iraq. “ISIS is so utterly grotesque and such a horror that one shouldn’t even speak of it as ISIS. One should call it Daesh as Middle Easterners do. At the same time, we cannot deny that ISIS is a direct product of the British and American intervention in Iraq. What is so horrifying is they are reproducing what happened to them in these American prisons. They are doing waterboarding, jumpsuits. The whole thing is so hideous it is almost beyond contemplation.”

Ghosh is an unflinching critic of British and American foreign policy. In addition to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, he argues that ISIL has been created in part by the Anglo-American governments’ failure to confront climate change. It is an unusual and intriguing notion.

“What is truly devastating about this Syria conflict is that we are reading it in the wrong way. It began with the 2008 drought in Syria. Hundreds of thousands of Syrian farmers had to leave their land. The drought continues throughout that Levant region. They became this huge disaffected underclass that ultimately became the prime movers of this Syrian insurgency.”

He accuses what he calls the primary climate change deniers: namely, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. “Essentially it is Britain and its settler colonies. It is the Anglo-American idea of economy and development. Britain saw these seemingly empty continents and squeezed them of their resources, then presented this to the world.”

His hope is that the dire political consequences of this ecological disaster expose the neoliberal fantasy of infinite economic growth as a lie. “For years they have been drumming into the world that the ideal life is an American suburban life with two cars, a dishwasher and a fridge. This was never possible in the first place. In India if everyone had two cars the whole country would asphyxiate.”

One can detect the origins of Ghosh’s commitment to environmentalism, and his own nomadic instincts, in his family’s history. “My family originally is from Bangladesh, a land that is completely subject to elemental forms of nature. The family lore is that we left its village in 1856 because the river changed course and drowned the village. In some sense my travels begin with my family becoming ecological refugees.”

Given his withering assessments of both American and British realpolitik, it is slightly ironic that Ghosh has spent long periods in both England and the United States. He and his wife, the writer Deborah Baker, divide their time between Brooklyn, Calcutta and Goa, where Ghosh does much of his writing.

A lifetime of restless globetrotting has produced a body of work that itself acknowledges few boundaries. Sea of Poppies for example is written in a dialectic English that has absorbed words from India, Persia, China and Arabic. Ghosh contrasts his transgressive, borderless novels with the self-regarding novels produced by many modern western writers: he points to the number of American novels that actually have the word “American” in their titles.

“I think fiction has been part of the problem,” he argues. “The western fictional tradition in the 20th century has become more focused on issues of identity, selfhood. It has become separated from the outside world. That has happened in a catastrophic way. Fiction has been the least responsive to what is happening to the world around it.”

Ghosh is profoundly aware that his is a vocation at a turning point – not only aesthetically but in economic terms. “I am perhaps one of the last generation of novelists who can hope to make a living from writing. The entire profession is in crisis. We have to find ways out of it. One of these is that every writer has to go around the publishing industry and create our own audience.”

This explains, in part, why Ghosh has enthusiastically embraced blogging and Twitter, where he has more than 40,000 followers. The problem remains, both online and at many literary events, that writers give their time for little reward. He argues that publishers have conditioned readers to expect to be able to interact with writers for free.

Ghosh offers a possible solution. “Publishing should take its cue from the music industry and should model book festivals on music festivals. People do get paid something. I feel this should become part of the revenues of the publishing industry. There are many writers who feel the same way.”

When I ask whether he can summon similar confidence about the world at large, Ghosh sounds considerably less optimistic. “The world should be very, very worried. The future to me looks very, very bleak. What astonishes me is all the happy talk I hear.” He mentions last week’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report urging drastic and immediate cuts of carbon emissions. “Even a pessimistic document like that is put together to seem more optimistic than the materials would allow. I think we are literally staring catastrophe in the face and we are sleepwalking towards disaster.”

Can anything wake us up? “I very much doubt it,” he sighs, citing the droughts afflicting California and the hurricanes that hit both New York and New Orleans. “In California they are literally using up their last drops of water. Are people aware of it? No, they are watering their lawns and carrying on as though there is endless water ahead. They have lived beyond their means, as the whole world has, for years, and the bill is coming due.”

By all means go and see Amitav Ghosh speak this week. Just prepare to leave a sadder if wiser human being.

• Amitav Ghosh will be discussing The Legacy of the Cairo Genizah at NYUAD Institute tomorrow from 6.30pm. To register, visit nyuad.nyu.edu. He is also appearing at the Sharjah International Book Fair on Thursday at 8.30pm in the Intellectual Hall. The book fair runs until Saturday; www.sharjahbookfair.com

James Kidd is a regular contributor to The National.