After the murder by ISIL of the Japanese hostage Kenji Goto, Jordan has vowed to do all in its power to save the captive pilot Maaz Al Kassasbeh. Have the terrorists changed tactics from ransom demands to genuine negotiations?

ABU DHABI // With the murder of the Japanese journalist Kenji Goto, the executioners of ISIL followed a familiar path – weeks of threats followed by the promised beheading, videotaped and then posted on the internet.

But the last days of the Japanese documentary filmmaker did differ from those of other hostages, with what appeared to be open negotiations with his captors to secure his release and that of the Jordanian air force pilot, Maaz Al Kassasbeh.

Demands by ISIL in the past have typically been restricted to substantial ransom demands of millions of dollars.

This time there was another factor – Sajida Al Rishawi, a failed suicide bomber sentenced to death for her part in a 2005 attack on a wedding in Amman, which killed 38 people.

ISIL has demanded her release, and Jordan has offered to comply in exchange for the return of first lieutenant Al Kassasbeh.

But are meaningful negotiations with ISIL pointless, beyond handing over huge sums of money? The group is holding two other western hostages – James Cantile, a British journalist captured in 2012, and a female American aid worker whose name has not been made public at her family’s request.

Can anything be done to save them?

Richard Mullender is an experienced hostage negotiator who was involved in the release of three United Nations workers in Afghanistan in 2004, and the rescue of Norman Kember, a British peace activist kidnapped and threatened with execution in Iraq in 2006.

Hostage negotiations, Mr Mullender says, have become increasingly sophisticated since the 1980s: “We’re getting better, and as we get better, they get better.”

Very few negotiations take place face-to-face.

“It’s down the end of a telephone if you’re lucky,” Mr Mullender yesterday told BBC Radio.

“And a lot of time, of course, they won’t engage with you by the end of the telephone anyway, so you have to use other methods to get your message across – the media, for instance.”

The key to any hope of a successful outcome is effective listening, he says. “You’re always looking to find out what it is that they’re looking to achieve.

“People don’t take hostages not to achieve something. Our job is to find an alternative way to achieve it without killing them.”

These rules apply even when dealing with groups like ISIL, who appear to have no desire to enter into a dialogue, Mr Mullender says.

“You have to listen,” he says. “You have to listen to why they are doing what they are doing. And it may not be that they are talking, but their actions themselves are telling you something.

“You’ve got to try to understand them. It’s no good trying to impose your values on somebody, it doesn’t work.”

Mr Mullender’s technique is to use expressions like “I get the impression” or “It sounds like” when negotiating, rather than asking probing questions.

“Instead of just asking a question you put forward a suggestion, and by putting forward a suggestion a person has two alternatives,” he says.

“The first one is to agree with you. If they agree with you they tend to expand on it, and if you’ve got it wrong they’ll disagree with you and say ‘No, that’s wrong’ and then tell you. So either way you find out.”

At same time, while it his job to stay neutral, he says: “It can be very difficult, especially when you see people do things that are absolutely against what you believe in.”

One of the most protracted periods of hostage taking took place in Beirut during the Civil War from 1982 to 1992, mostly by Shiite radical groups.

During this period up to 100 foreign hostages were taken, with at least 10 murdered by their captors, including William Buckley, a CIA station chief, and Alec Collett, a British journalist who was writing about Palestinian refugee camps for the United Nations.

Among those held was also Terry Waite, a Church of England negotiator who travelled to Lebanon to try to secure the release of a British journalist, John McCarthy.

Waite was kidnapped in 1987 and was at one point reported to have been killed. But he was alive, and his release was secured four years later, in 1991.

McCarthy was also freed at this time, as was Terry Anderson, an American journalist who spent six years in captivity.

One of those most instrumental in their release was Giandomenico Picco, now an under-secretary general for the UN.

It was Mr Picco who negotiated with Imad Mughniyah, a commander with Hizbollah and Islamic Jihad, and thought to be behind the kidnapping of many westerners. He was killed by a car bomb in Damascus in 2008.

Two years ago Mr Picco explained in detail the negotiating process for the first time.

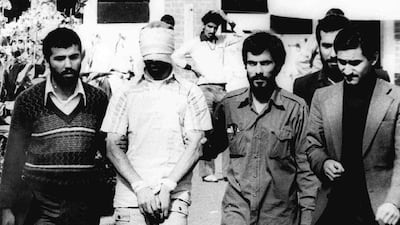

He was blindfolded, then taken by masked men to meet a man he later learnt was Mughniyah.

He wrote that the head of the kidnappers told him that he did not expect him to be impartial and that he also knew taking hostages was wrong. But he said: “We have no other tool.”

“Having been involved in face-to-face negotiations in other cases, I have long learnt that impartiality does not exist,” Mr Picco wrote. “We all have our own narratives, both national and individual, that are the core of who we are and what we do.

“Thus the key to successful negotiations with adversaries is to discover – not to share necessarily – some or one page of their narrative, for there is the soil in which the roots of their decisions are born.”

For Lebanon hostages, the key turned out to be a report issued by the UN blaming Saddam Hussein for the 1980 to 1988 war between Iran and Iraq.

With the release of the report, Iran – feeling vindicated – pressured Hizbollah to free the hostages. No US money directly exchanged hands, Mr Picco claims.

For some observers, the decision by ISIL to seek negotiations for a prisoner release rather than a simple demand for cash is a sign that the organisation is evolving, even as it continues to commit terrible crimes.

And that means they may eventually join the list of pariah organisations that eventually win some degree of acceptance, says Jonathan Powell, a former chief of staff for former UK prime minister Tony Blair.

Mr Powell, who represented the British government in talks with the IRA that led to the Good Friday Agreement, has since founded Inter Mediate, a charity that aims to resolve international conflict.

“It is easy to regard any suggestion that we should ever talk to people capable of such savagery as immoral,” he wrote in The Guardian newspaper in October.

But he says: “Our past experience therefore suggests there is little alternative to talking to an armed group if we want them to stop fighting.”

In the end, that talking may be the best hope of saving the lives of ISIL’s remaining hostages.

plangton@thenational.ae