When Mahindra Singh Pujji left his native India in 1940 to answer a call from Britain's RAF for pilots to help their defence against Germany, it was not politics, but rather an appetite for adventure, that motivated him.

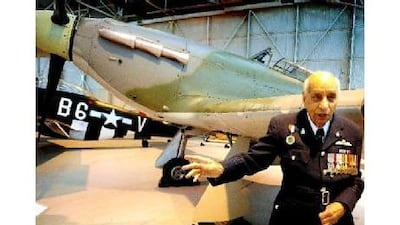

Twenty-four years old at the time, he was one of the first 24 Indian pilots to be accepted by the RAF. Of the original 24, 10 were killed in action or in flying accidents. But Pujji had luck on his side: in total, he served in five theatres of war, Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, Palestine and Asia, and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

His first action was with the 253rd (Hyderabad) Squadron operating a Hurricane (his plane bore the name "Amrit", the name of his fiancée at the time, later his wife) in a series of sweeps across occupied Europe accompanying British bombers. Rather romantically, he initially mistook the anti-aircraft fire directed at the planes for a field of flowers. Fatalities were high: "On my first day there were 30 pilots at breakfast," he recalled. "And we were never 30 again." The first to be shot down was Pujji's roommate. Yet Pujji never admitted to any fear. Rather, he was avidly curious, and in turn was regarded as something of a novelty by his fellow officers. In his first week on the job, he almost broke the record of running from the room where the pilots sat waiting to be called: he was out of his seat and up in the air in 20 seconds.

At the end of 1941, he was posted to North Africa, where he said he found the food particularly unappealing. In England he survived on chocolate and was provided with extra rations, together with a daily breakfast of two eggs. In North Africa, his diet consisted of biscuits: "You needed a hammer to break them," he recalled. He was sent to Cairo every weekend, where he would treat himself to a decent meal.

His next posting was to India, where he was assigned to the North West Frontier, the most dangerous portion of his career. A fellow RAF pilot who was shot down and fell into the hands of Sarhaddi rebels was "literally cut to pieces". A period in Burma followed, in which he took over a squadron going up against Japanese Zero fighters. Up until the 1960s, he insisted on wearing the turban, which was mandatory to his Sikh religion, even though it was somewhat impractical in a cockpit. Although he credited the six feet of wound fabric as a life-saver, absorbing the impact of his crash-landing after a fight over the English Channel, his son, Satinder, also remarked that the turban had cost his father a lung, damaged at high altitude, as the squadron leader could not wear his headgear and an oxygen mask simultaneously.

Invalided from service in January 1947 after a diagnosis of tuberculosis, and given six months to live, Pujji left the Royal Indian Air Force and took up the position of Aerodrome Officer at Safdarjung Aerodrome in Delhi. He continued to fly in a civilian role, becoming a prominent figure in the nascent gliding movement in India. He taught two young women aerobatics on gliders who were as committed to wearing their saris throughout as their instructor had been insistent on wearing his turban.

The son of a senior government official in Simla, Pujji read law at Bombay University and learned to fly at Delhi Flying Club, receiving his 'A' licence in April 1937. His first job was as a line pilot with Himalayan Airways, but he moved to Burmah Shell the following year to work as a refuelling superintendent. In 1939, with the outbreak of the Second World WAr, the newspapers carried advertisements inviting applications from 'A' licence holders for a volunteer reserve commission in the Indian Air Force.

Although Pujji found the British most welcoming when he arrived in 1940, he later expressed regret that Indian members of the RAF had received no special commendation for their participation in the war effort. His loyalty to Britain remained undimmed, however, and he lived in London, and then Kent, until his death.

Born August 14, 1918. Died September 18, 2010.