Midway through a week-long state visit to India, Canada’s prime minister Justin Trudeau is facing an unusually cool reception from prime minister Narendra Modi’s government.

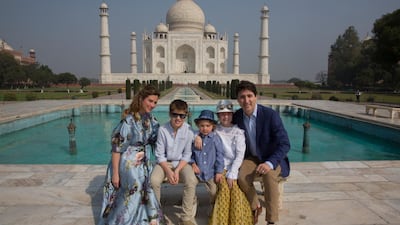

Mr Trudeau, who landed with his family in New Delhi on Saturday, has travelled to Mumbai, to Agra to see the Taj Mahal, and to Ahmedabad, a city in Mr Modi’s home state of Gujarat. But his single interaction with the prime minister is limited to a planned half-day of talks on Friday.

For Mr Modi, this amounts to a cold shoulder. The Indian prime minister has been known to break protocol and greet leaders at the airport as they land, enveloping them in his trademark bear hug. He always sends out messages of welcome to visiting dignitaries on Twitter, and has frequently accompanied them on their trips to Gujarat.

No senior government minister has made time to meet with Mr Trudeau. The chief ministers of Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh, where Mr Trudeau travelled, have not met the Canadian delegation either.

Analysts see the treatment of Mr Trudeau as a diplomatic snub — a signal that India is unhappy with the young prime minister's tendency to pander to Canadian Sikhs who want an independent Sikh state to be carved out of India.

Unnamed sources in the Indian government insisted, in media reports, that no snub was intended. But Mr Trudeau himself was forced to respond on Wednesday to questions about India’s reception, denying that he felt slighted or snubbed.

His government, he had said on Monday, has been “unequivocal on our policy of one united India".

Mr Trudeau is also facing heat at home. The Canadian Taxpayers Federation, an Ottawa-based non-profit, said in a statement that “the proportion of time being spent actually meeting foreign counterparts on this trip does not suggest a good use of public money".

The Sikh separatist movement, to create a nation called Khalistan around the north Indian state of Punjab, began in the early 1970s. At its peak, through the next two decades, it witnessed an armed insurgency which was put down, often violently, by the Indian state. In retaliation, then-prime minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her two Sikh bodyguards in 1984.

_______________

Read more:

Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau makes first state visit to India — in pictures

_______________

The movement found heavy support and financial backing from many Sikhs who had emigrated to Canada. At least half a million Sikhs live in Canada, a large proportion of them in the metropolitan regions of Toronto and Vancouver.

A pro-Khalistan group with members in Canada was responsible for the mid-air bombing of an Air India plane flying from Montreal to London, en route to Bombay (now Mumbai).

In India, as the government’s crackdown continued, Sikh extremism dwindled dramatically after the 1990s. But a concern about the movement’s revival “cannot be downplayed,” said Pranay Kotasthane, who heads the geostrategy programme at the Takshashila Institution, a Bengaluru-based think-tank.

Last December, the Indian government revealed to parliament that Pakistani intelligence operatives “are making efforts towards moral and financial support to pro-Khalistan elements for anti-India activities as well as to revive militancy in Punjab.”

In the US and in Canada, pro-Khalistan groups openly call for a referendum in Punjab, to vote for or against a Sikh nation. “What started as a diaspora extremist and terrorist movement has now gained support in the realm of politics as well,” Mr Kotasthane said. “Understandably, India is concerned.”

In trying to engage with Sikh communities and gaining their votes, Mr Trudeau has soft-pedalled the issue of Khalistani separatism, said Vivek Dehejia, a professor of economics at Carleton University in Ottawa.

The Trudeau cabinet has four Sikh ministers, one of whom was accused, by the Punjab chief minister last year, of having Khalistani sympathies.

“More disturbingly, Mr Trudeau attended the Khalsa Day parade” — organised by Sikh religious groups — “a couple of months ago,” Mr Dehejia said. “This was a parade where there were pro-Khalistan banners, and banners honouring the martyrs of the movement.”

The Ontario Sikhs and Gurdwara Council, which organises the parade every year, did not respond to requests for comment. Mukhbir Singh, president of the World Sikh Organisation, said in a statement: “There is nothing to indicate any rise in radicalism.”

“Peacefully advocating for political causes cannot be confused with or tarnished as radicalism,” he said. “These bizarre allegations made against Canadian Sikhs are incredibly damaging and result in actual harm against the community.”

Though Mr Kotasthane saw India’s reasons for concern with Khalistan, he disagreed with its diplomatic stance towards Mr Trudeau.

“Surely India has many more matters of national interest to be discussed with Canada apart from the Khalistan issue alone,” he said.

Additionally, “giving a cold shoulder to a head-of-state on a pre-planned visit doesn’t seem to be the best way to address India's concerns related to Khalistani networks in Canada”, he said. “This is unlikely to make Canada alter its stance.”