As with all good things, spending sprees must come to an end.

Analysts are reporting a large consumer-behaviour shift in luxury goods and it's being reflected in the stock market performances of the sector's largest companies.

Shares in the world's largest luxury goods company, LVMH, took a dip recently, after the maker of Louis Vuitton handbags and Christian Dior fashion reported third-quarter figures below expectations, prompting some commentators to reach for their Montblanc pens and write that the boom in high-end goods was finally over.

Because LVMH is such a bellwether stock for the sector, shares in its rivals such as Kering, Hermes, Swatch, Richemont and Burberry have also lost ground recently – since April this year, about €166 billion ($175 billion) has been knocked off the value of Europe's 10 leading luxury good stocks.

The phenomenon that what happens to LVMH spreads throughout the luxury sector was illustrated this week by its rival Kering, which announced a 9 per cent fall in third-quarter sales at Gucci, the brand that accounts for two thirds of its operating profit.

Soaring inflation and the associated rise in interest rates that have characterised the end of the era of cheap money has given some of those with designs on luxury items pause for thought.

But is the party really over, or is it just a temporary blip?

Haves and want-to-haves

It is important to remember that there are essentially two types of luxury goods consumers: the have-everythings and the want-to have-everythings.

In other words, there is a group of customers of luxury goods that are so rich that economic headwinds, recessions, stagflation and the like make no difference to their buying power or patterns. Then there are the aspirational buyers – rich by most people's standards, but still having to navigate the world's economic and financial tempests.

"The aspirationals have already been on the decline for the past two years and now we're even seeing at the upper end that there's some slowing down,” said Pauline Brown, author of Aesthetic Intelligence: How to Boost It and Use It in Business and Beyond and a former chairman of LVMH for North America, told The National.

"Growth over the last one to two decades has come disproportionately from the want-to-haves and not just the ones in the US and Japan.

"There was zero luxury market in China 30 years ago and these are brands that have been around for centuries.

"So, you went from zero to the largest luxury market and consumer base in the world in less than three decades. And that was all the want-to-haves."

Best foot forward

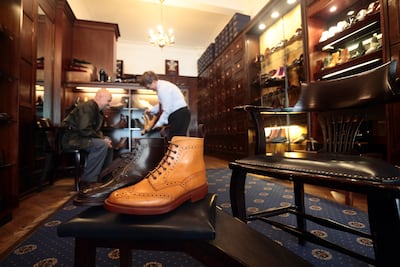

In luxury shoemaking, it is the last thing you want. That's because a "last" is the three-dimensional mechanical device shaped like a human foot that has been used for centuries in the crafting of footwear.

Tricker's, which is Britain's oldest shoemaking business and holds a royal warrant to supply King Charles III with footwear, uses lasts that were first created in 1937, meaning their products have a classic luxury design.

Prices for Tricker's "Bourton" shoes and "Stow" boots start at about £500 ($610), somewhat below a pair of $10,000 Louis Vuitton Manhattan Richelieu shoes, but still comfortably within the luxury goods market.

Tricker's managing director Martin Mason told The National there is a "definite movement in luxury shopping globally", where well-heeled buyers are increasingly looking for quality and craftsmanship, rather than snapping up a particular brand simply for the name itself.

Geographical differences

While large global players such as LVMH have economies of scale on their side when it comes to weathering a fall-off in aspirational luxury goods buyers, others are not so fortunate.

Smaller luxury goods makers are more at risk to the loss of aspirational shoppers and in the UK, companies argue tax rules place them at an even greater disadvantage.

The "tourist tax" is essentially the inability of overseas visitors to reclaim UK value-added-tax (VAT) on their purchases, something which before 2021 they were allowed to do.

"We are now charging 20 per cent more than other countries do for the same goods," Mr Mason of Tricker's told The National.

"International visitors, who we should be doing everything we can to encourage to come here, won't hesitate to go elsewhere and we are seeing the effect in our central London store."

Tricker's has shops in London, Tokyo and Shanghai, but Mr Mason says the UK tourist tax makes luxury shoes made by competitors in Europe more attractive, even for British visitors.

"Every country remaining in the European Union now offers tax-free shopping, while the UK does not, putting our economy at a significant disadvantage," he told The National.

"Even British shoppers visiting EU countries can shop tax-free. Competitor cities such as Paris, Rome and Milan can’t believe their luck."

'Muddied outlook'

The turmoil in China's property market and the resultant drag on the country's growth has meant less luxury spending in the world's second-largest economy.

According to Hong Kong's Census and Statistics Department, the value of luxury goods sold was HK$5.2 billion ($665 million) in August this year, a decline of 31 per cent on the same month in 2018.

Recent third-quarter figures from Mercedes-Benz showed sales of its ultra-luxury vehicles such as the S-Class decreased significantly.

Global sales of S-Class models fell 18 per cent when compared to the same period last year, while sales in China, the company’s biggest market for the car, fell 12 per cent.

Tesla's chief executive, Elon Musk, recently voiced his worries over higher borrowing costs being a barrier to people potentially buying the company's cars, despite some significant price cuts.

In addition, the chief financial officer at the luxury car maker Porsche, Lutz Meschke, this week said inflation concerns and economic uncertainty were affecting the luxury sector.

"You can follow it when it comes to share-price development of all luxury retailers worldwide," he said.

So, while China's patchy post-pandemic recovery has been exacerbated by problems in its property market, the economies of the US and Europe have been punctuated by a cost-of-living crisis that has seen a rapid rise in borrowing costs as central banks seek to stamp on inflation.

As such, Piral Dadhania, an analyst with RBC, described the outlook for the luxury market next year as remaining "muddied," while forecasting that downwards profits revisions for luxury companies would most likely continue.

However, others caution on being too gloomy about the prospects for the likes of LVMH.

Those three successful years were certainly good to shareholders of LVMH and other luxury goods makers.

Between March 2020 and July 2023, shares in LVMH gained 177 per cent, as the world's rich and affluent indulged in a post-pandemic luxury spending spree.

“After three roaring and outstanding years, growth is converging towards numbers more in line with the historical average,” LVMH's chief financial officer Jean-Jacques Guiony said during the quarterly results presentation.

Last month, LVMH lost its crown as Europe's most valuable company to Danish drugmaker Novo Nordisk, which is currently riding high on the stock markets thanks to its obesity treatment, Ozempic.

In a research note, JP Morgan analysts said LVMH is among the luxury goods companies that "should navigate this ongoing volatility relatively better".

For example, revenue at LVMH's crucial fashion and leather goods unit, which includes Louis Vuitton and Christian Dior, rose 9 per cent in the third quarter.

While that was below what analysts were expecting and is half the pace of growth achieved in the first six months of 2023, it's hardly a disaster.

Also, Christian Dior, which is LVMH's second-biggest fashion label, has tripled in size in fewer than seven years, a performance which Jean-Jacques Guiony said is impressive, but not sustainable.

“At some point, growth rates have to normalise,” he said. “Don’t expect the brand to continue to grow 30 per cent per annum for ever. It will not happen.”

All of which highlights what Luca Solca, an analyst at Bernstein, calls “a sign of continuing moderation, as consumers sober up after the post-pandemic euphoria”.

'Luxury is not going away'

Meanwhile, Ms Brown, who is also an associate professor at Columbia Business School, feels the analyst community might have felt a more profound sense of shock at LVMH's third-quarter results than might have otherwise have been the case, because the numbers came in below expectations, something that is very rare indeed, and so the figures "rattled the investment community".

In the short-term the luxury goods sector may be rattled by the retreat of recent aspirational buyers and the introduction of new ones.

"I think that a lot of the luxury companies were looking, and maybe disproportionately so, at Generation Z as sort of a next big wave post-Millennials," Ms Brown told The National.

"I always felt that was a bit misguided because my experience of Gen Zs is that, not withstanding their dreams and desires, they have a lot of student debt, particularly in America. And they're not at the point where they can spend freely as aspirational consumers.”

However, at least part of that problem is alleviated by advances in longevity and what might be called "health span", as older luxury goods consumers stay healthier for longer and, as such, remain buyers for longer.

In addition, Ms Brown told The National, because desire and aspiration are hard-wired into much human behaviour, the luxury sector's future will, for the most part, remain golden.

Louis Vuitton through the years - in pictures

“LVMH is not going away and luxury is not going away," she said.

"In every culture around the world, every market, every age group and if you go back historically, every chapter of mankind there has been some form of luxury or some aspirational demand.

"So, that's just sort of a universal thing that doesn't go away.”