As the apocalyptic devastation of the first earthquake on February 6 raged in Turkey and Syria, one of the images almost immediately shared around the world was of the outer walls of Gaziantep Castle, tumbled like giant sugar cubes.

Why, when there was such traumatic and significant loss of life in an ongoing human, environmental and economic tragedy would anyone care about damage to a heritage site? Yet this picture went viral, swiftly followed by others: the crumpled minaret of the Sirvani Mosque, the collapsed Cathedral of the Annunciation in Iskenderun and the damaged synagogue in Antakya (ancient Antioch).

In January, Unesco added three locations to its official catalogue of endangered heritage monuments – Yemen, Lebanon and Crimea. In the face of global-scale conflicts and political disruption, you might think this an irrelevant, esoteric indulgence. But that would be to miss a crucial point.

There is a false dichotomy when it comes to care and concern for human life and for the works of human hands, heads and hearts. Historic buildings are freighted with meaning and memory. Heritage which has endured the vicissitudes of time carries with it the experiences and skills, the passions and preoccupations, the hopes and fears and ambitions of generations' worth of individuals, women and men, young and old.

These tenacious buildings are repositories of local pride. They are places that connect us, across time, with other humans. Because they make us care about other lives, and encourage us to understand them, they come to carry universal meaning.

Take that shaken Gaziantep Castle – a stalwart incarnation of the diverse, multi-cultural history of the region. Built in the Bronze Age originally as a Hittite lookout by the Anatolian civilisation that once controlled huge swathes of what is now Turkey, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq, the hillfort was then taken over by Roman imperialists, and redeveloped by the Byzantine emperor, Justinian I. The Ayyubid dynasty of the Sultanate of Egypt – founded by Saladin – further extended the fortification, as did the Ottomans. Gaziantep Castle was the locus of resistance to French troops in 1920 during Turkish War of Independence, and proudly boasted a display of artefacts from that time in the Gaziantep Defence and Heroism Panoramic Museum.

Unesco’s other newly listed at-risk locations have similar, capacious stories to tell. The ancient Kingdom of Saba in Yemen was a pivot of the frankincense trade that connected the southern Arabian Peninsula with Alexandria, the Levant, the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond.

Frankincense from Yemen and Oman ended up on the altars of temples and elite homes in Rome, Babylon, Cyprus and China. Saba was an engine of life, and the traders who started their journeys here via desert and sea routes, often with camel caravans 1,000-strong, took with them not just goods but languages and ideas.

Now threatened by conflict, ancient Saba was once an object lesson in collaboration – here community irrigation systems that functioned only thanks to a trustworthy time-share of water for 2,000 years created the continent’s largest man-made oasis.

Odesa in Crimea – currently witness to a war of attrition and once controlled in turn by Greeks, tribal Pechenegs and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to name but a few – was in its 19th-century heyday an exemplar of multi-ethnic and cultural co-habitation. The vision and cohesion of the planning of the modern city – kickstarted by Catherine the Great and realised, in the majority, by Italian architects, is now being splintered apart by aerial attack.

Even the Rachid Karami International Fair in Tripoli, Lebanon, designed between 1962 and 1967 by the Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer, and which ushered in a new outlook for the Arab world, now has to be protected not only because of its vulnerable, eroding and corroding concrete and steel, but because of state and social breakdown. All these sites are in clear and present danger because of political insecurity.

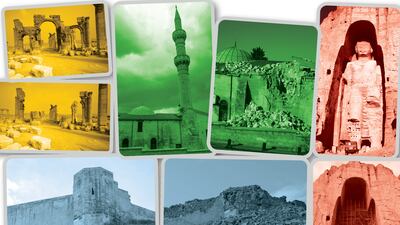

The very fact that monuments are regularly the target of attack during conflict proves their relevance. When the Buddhas of Bamiyan were destroyed in 2001 (after many previous attempts from the 13th century onwards), the message was being sent that 1,500 years counted for nothing in the face of one second of dynamite.

The destruction of antiquities at Palmyra, Syria was the frame within which the brutal and despicable beheading of its chief curator Khaled Al Asaad was positioned. Mr Al Asaad’s sacrifice to protect the whereabouts of the artefacts under his care proved his nobility, and the shared meaning of Palmyra’s heritage.

It's not just Unesco – previous cultures have understood the need to maintain buildings despite their incarnation of opposing ideologies. In 393 AD, a temple in Osrhoene, Mesopotamia was ordered to remain open so that the works inside could be enjoyed “for the value of their art rather than divinity” and a constitution of 399 AD was passed by the Byzantine emperors Arcadius and Theodosius that prevented individuals destroying polytheistic artworks (although there was mass destruction in the imperial name of the newly Christianised Eastern Roman Empire).

The protection by Unesco of the unique monuments on its World Heritage in Danger list is an act of wisdom and will. Powerful civilisations leave behind great monuments, great civilisations leave behind powerful ideas.

The Unesco listing brings responsibilities, maintenance, management, marketing. But it is also a strategy that connects the local to the global. When filming in the earthquake-struck region of Turkey this time last year, the swelling pride of Malatya locals in their new Unesco status heritage was clear to see. Bulent Korkmaz, a resident whose family have farmed the land here for generations, delightedly showed me around Arslantepe, an 8,000-year-old prehistoric site believed to be a home of one of the earliest examples of statehood, and of the world’s oldest swords.

Having explored and documented the new archaeology of the region, those we met have beseeched us post-earthquake to transmit our film to remind a global audience how beautiful and rich south-eastern Turkey normally is, and how beautiful it will be again.

Spending time recently in Jordan with female apprentices on the World Monuments Fund’s training programme for heritage stonemasons also rammed home the power of involvement in heritage as a form of extreme art therapy.

Two of the displaced women I met, Khadija and Aisha, agreed that despite the fact they had to leave their homelands and move to Mafraq just across the Syrian border, learning apparently arcane skills made them realise they were as strong as any man. Their mental health benefitted not only because they felt a direct connection to, and respect for, the artisans of the past who had created beauty out of stone here for millennia, but because they had the opportunity to build and to create, rather than witness the systematic destruction of heritage that had become the trauma of their life experience.

Unesco’s list of endangered sites is not just a collection of sterile stones. We are creatures of memory. Neuroscientists now tell us that we carry memory right across our brains; we cannot have a future thought unless we access a memory of some kind – of an experience, an idea, a sensation. So denying our collective history does not just ignore our past, it weakens our present and cauterises our future potential. We should never live in the past, but we are fools if we don’t admit that we live with it.

Bettany Hughes's Treasures of the World Season Two is currently playing internationally and in the UK. Her forthcoming book, The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, will be available in the autumn of 2023