If football is the usual talking point of any Fifa World Cup, then the stadiums built for the Qatar tournament will almost certainly run it a close second.

Previous World Cups have largely involved refurbishing existing stadiums to bring them up to the standard expected of the world’s greatest feast of football.

For Qatar, seven new arenas have risen out of the ground in only a few years. The eighth, Khalifa International Stadium, has been renovated so extensively it is almost unrecognisable.

It is a remarkable achievement for a country whose domestic football league is only 50 years old and where the number of spectators for the biggest games typically runs into the hundreds.

To put it another way, the entire population of Qatar, excluding guest workers, could comfortably fit into the eight stadiums at the same time — with about 50,000 seats still going spare.

Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy

For the World Cup, the eight arenas, with a total capacity of 420,000, will probably be bursting at the seams. This is a chance for the country to display its glittering best, at a cost estimated at $220 billion, including a new metro.

The new stadiums alone have a price tag estimated at $10 billion, or an average of $1.25 billion each, Hassan Al Thawadi, the Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy's secretary general, said in 2016.

It also means the cost for each day of use for a single stadium in what is only a four-week competition is a staggering $357 million. When the winners lift the golden Fifa World Cup trophy on December 18, Qatar will need to recalibrate its investment.

Each stadium has its own legacy plans. One will disappear completely. Stadium 974 — the name derived from Qatar’s international dialling code — is made entirely from recycled shipping containers.

With a capacity of 40,000, the first temporary stadium in the history of the World Cup broke ground in 2018 and was completed three years later.

Built on an artificial promontory next to the port of Doha, the stadium will be dismantled after the World Cup with the site to become a waterside business park.

The roof and seats will be donated to other sporting projects outside Qatar. As for the shipping containers — which also number 974 — it’s not clear how many will return to active duty on the high seas.

In a document, Mr Al Thawadi said the committee recycled and reused materials where possible during construction and consulted local communities before deciding on how best to repurpose the stadiums.

"We used materials from sustainable sources and implemented innovative legacy plans to ensure our tournament doesn’t leave any ‘white elephants’," he said.

"To achieve this particular goal, we canvassed local communities to find out what facilities they needed and implemented their ideas and suggestions into stadium developments and precincts.

"The result is detailed legacy plans, including a proposal to remove the modular upper tier from several stadiums and donate the seats to countries in need of sporting infrastructure."

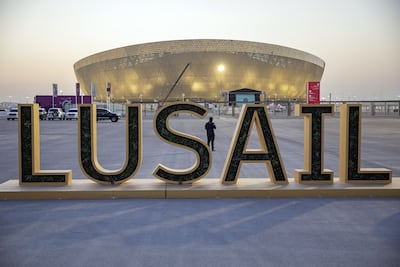

Lusail Stadium, this year's tournament's biggest with a capacity of 80,000, will host the World Cup final, but never see another game of international football. Designed by architects Foster+Partners, the huge golden bowl will have most of its seats stripped away and be repurposed for shops, cafes and possibly a school and health clinics. The upper tiers will be transformed into housing, while the pitch will be used for community games.

Al Bayt Stadium, the second largest, has a tent-like design which honours Qatari heritage and will host the opening game, as well as quarter-finals and a semi-final.

It, too, will radically change after the tournament. The upper tiers will be removed and replaced by a new five-star hotel, shopping centre and sports medicine hospital.

Running through all this is Qatar’s desire not to be left with a collection of abandoned and derelict stadiums, as has happened with previous host nations.

Brazil’s 2014 World Cup left many cities struggling with expensive maintenance costs for stadiums that, in some cases, now house merely a few hundred spectators. Arena da Amazonia cost about $250 million to build in Manaus, an area in the middle of the Amazon that is difficult to reach and has now been virtually abandoned.

Greece spent about $11 billion when Athens hosted the 2004 Summer Olympics — almost double the initial budget. It was the most expensive Olympics at the time and helped bring about the country's financial crisis in 2007-2008.

The Hellinikon Olympic Canoe / Kayal Slalom Centre once seated 7,600 spectators and its course was filled with salt water for the world's greatest teams to compete. Today, almost 20 years on, the water is drained with weeds having grown through the cracked concrete. The centre is one of many purpose-built arenas in Athens that have since been abandoned and are slowly succumbing to the elements.

A site for the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, Chaoyang Park Beach Volleyball Ground, met a similar fate after being built for the games. The court, which holds 17,000 tonnes of sand, once seated 12,000 people but is now used for an annual beach festival. It was used for its intended purpose only twice more after the games, when it hosted the FIVB Beach Volleyball World Tour in 2011 and 2012.

Qatar’s strategy for avoiding this has been to downsize aggressively once the World Cup is over, offering the redundant structures, amounting to about 170,000 seats, to poorer countries looking to improve their sporting infrastructure.

The technology behind the cooling systems developed for seven of the eight stadiums has deliberately not been patented, allowing other countries and businesses to use it free of charge.

It was developed by Saud Abdulaziz Abdul Ghani, a professor of engineering at Qatar University, who calls the technology “a potential game-changer for countries with hot climates. That is why I made sure that anyone can use it”. He calls it “one of Qatar’s many gifts to the world”.

Ahmad bin Ali, Al Janoub and Al Thumama Stadium will all have their capacity cut to about 20,000 spectators post-World Cup, although even this may be optimistic given normal attendances.

Two of Qatar’s biggest clubs will make the former World Cup stadiums their home. Al Rayyan, eight times winner of the Qatar Stars League, will move into the Ahmad bin Ali, while Al Wakrah will make Al Janoub their home.

Education City Stadium will also be cut from 40,000 to 20,000 capacity and, as the name suggests, will become a sports ground for university students.

Only Khalifa International Stadium will remain. First built for the 1976 Gulf Cup, it was renovated for the 2006 Asian Games and upgraded again to Fifa standards in 2017, and now has an additional 12,000 temporary seats.

More international sporting events are lined up for the stadium, including football and athletics, and it will also serve as a monument to the 2022 World Cup.