After a nuclear crisis in Fukushima, 200 Japanese pensioners volunteered to face the dangers of radiation instead of the young. The cancer could take several decades to develop, meaning they would no longer be alive to experience it. Yasuteru Yamada, the 72-year-old who organised the retired engineers, teachers and cooks, told the BBC that their decision was “not brave, but logical”.

The Greeks believed that “a society grows great when old men plant trees in whose shade they know they shall never sit”. What might that mean today? Becoming a good ancestor means learning to become better story bearers and filters, confronting injustice and finding ways to forgive and be forgiven.

Firstly, by being story bearers. Our ancestors had a much stronger sense of the circle of life, the passing of the seasons and years. It was hardwired into the social calendar, the rituals and the rites of passage, and was often the glue that held together communities. The stories were preserved, embellished, cherished, shared. Perhaps this is why so many in the second half of their lives become so obsessed with tracing family history. We find ourselves wanting to walk where they walked, to handle objects that they handled. Advances in DNA testing enable us to dig back even further, following the trails back through centuries as our ancestors moved through continents. We are all migrants.

What is harder, beyond the apocryphal tales of distant relatives, is to preserve their values. We form a sense in our family narratives about recent ancestors. But despite all the search engine-propelled research, we know less about our great grandparents than they did about theirs. Our sense of community and calendar has been bent into a different shape by several centuries of urbanisation and several decades of globalisation. Netflix and central heating replaced the campfire.

Secondly, to become filters. The role of our ancestors in conflicts affects us psychologically, influences our relationships with family and friends, and contributes to our propensity to participate in the next wave of strife, and to pass it on to the next generation. All of us carry historical trauma, even if we cannot see or comprehend it. Geneticists have shown that the behaviour of our genes can be altered by experience – and can be passed onto future generations. Life experience, stress and trauma can change the expression of our genes. The grandchildren of holocaust survivors have altered stress responses because of the experiences that they had either when they had a child in the womb or around the time of conception or even before.

So we bear a huge responsibility for whether, through our beliefs and behaviour, we transmit these traumas and grievances to our children, an inheritance that has far more potential to shape their lives than the contents of a will. We can start to reconcile with the past and the future by reflecting on two challenging questions. What did I inherit in terms of family values and history that I must pass on? What did I inherit that I must not pass on?

In the answers lie real secrets to survival, and the key to being a good ancestor ourselves. Most people spend a lifetime figuring them out. But being a good filter is an act of ancestral therapy.

Thirdly, by confronting the systemic, underlying injustices that our descendants will hold against us. Will they venerate our statues, or tear them down? Three of those injustices are inherited inequality, inherited climate crisis and inherited conflict. To help us to do that, perhaps the curriculum of the future will teach uncertainty, dissidence, scepticism, curiosity, ethics and solidarity. Write down the three biggest systemic advantages you had, and how they have changed your prospects at crucial moments. It might have been the right school, the subtle advantage of gender or race at a job interview, or a word in the right ear from part of your inherited network. Be really honest, setting aside the story you might choose to tell yourself.

Then imagine the experience at those crucial moments of someone who was denied those advantages. What will you do now to even the playing field?

Finally, being a good ancestor requires us to practise one of the hardest yet most vital survival skills: to seek and to offer forgiveness. In 2010, I worked with then British prime minister David Cameron on his response to the Saville Inquiry into Bloody Sunday, the 1972 killing and injuring of unarmed civilians by British soldiers in the Northern Ireland city of Derry. His apology was so powerful because it was authentic and sincere – a defining moment early in his administration, when he moved from being the leader of the largest party to being the prime minister. It recognised the context in which the situation had occurred, but did not blind itself to the hurt caused. He thought hard about how it would be received not just among the UK military and his own constituencies, but how those on the streets of Derry would react.

At moments in history, nations have found ways to adopt an atonement strategy, of seeking collective forgiveness. Former German chancellor Konrad Adenauer led this effort to atone for the holocaust. Only days after taking office in 1949, he set out what has subsequently become the core elements of national atonement: a verbal acknowledgement of moral responsibility for the wrongdoing; a public expression of remorse and reconciliation, and the offer of restitutive actions including financial, legal or political measures.

Perhaps there are elements of this model that can help us to say sorry? Acknowledging our share of responsibility. Expressing remorse and reconciliation. Coming to terms with the past. Making good again.

Forgiving might be even harder, but it can be done. In November 2015, two days after terrorists killed 89 people in an attack at the Bataclan theatre in Paris, the writer Antoine Leiris wrote a powerful open letter to them on Facebook. His wife had been among those murdered.

“On Friday night, you stole the life of an exceptional being, the love of my life, the mother of my son, but you will not have my hate. I don’t know who you are and I don’t want to know. You are dead souls ... You want me to be scared, to see my fellow citizens through suspicious eyes, to sacrifice my freedom for security. You have failed. I will not change.”

He insisted that his baby son’s happiness would also defy them: “Because you will not have his hate either.”

Every unforgiven trauma in our own lives, large or small, causes pain and corrosion. We need to find ways to forgive those who have harmed us. This forgiveness can extend to our ancestors or the ghosts in our families. Ultimately, it must also extend to ourselves.

What is the injustice, or perceived injustice, towards you personally that angers you most? How is it corrosive? How could you begin to feel your way to forgiveness? What are the small moments of communication and connection that can start the healing process?

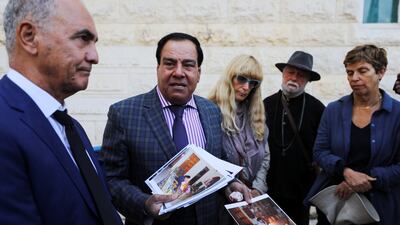

In 2020, I interviewed Palestinian doctor Izzeldin Abuelaish at the first Hay Festival in Abu Dhabi. Izzeldin’s story is inspiring and devastating. Living in Gaza and the first Palestinian doctor to practise in Israel, he endured the checkpoints and grinding humiliation every day for his profession and his family, even after his wife Nadia died. He had seen two family houses bulldozed by Israeli general (and later prime minister) Ariel Sharon, the second to make the street in the ramshackle refugee camp wide enough for tanks to pass through.

But worse was to come. During Israel’s bombing of Gaza – bearing the terrifying title Operation Cast Lead – in 2009, he lost three beloved daughters and a niece in a single attack. The Goldstone Inquiry later called the operation “deliberately disproportionate”. His daughter Mayar had said that she wanted her kids to “live in a reality where the word rocket is just another name for a space shuttle”.

She never saw that reality.

I found it very hard to find the words and questions to capture all this. In the end, all I could do was to ask Izzeldin to talk. He chose his words carefully, stepping through his memories like a man crossing a minefield. He described the sabra plant that grew on the land his family lost after the Israeli occupation. It is tenacious and resilient. He described how his daughters wrote their names in the sand on their last beach trip together. And kept rewriting them even when the sea washed them away. “I never tried to teach them resilience, only to see other people as like them, even their enemies. I learnt patience at those checkpoints, even while Nadia was dying.”

We wept together on the stage. The wounds are raw, and will never heal. How do you heal from holding the broken and smashed bodies of three daughters? What more could I say than that we stood there in witness and solidarity?

Izzeldin sobbed. I reached across and gripped his arm, unsure how to react. His voice was quiet.

“You can never expect the pain to go. And you can show courage simply by remembering them. By carrying on. “I can never not hate what they did to my daughters. But I can choose not to hate them.”

Time slowed. No one moved in the silent auditorium. We felt a powerful sense of empathy, but also a powerless sense that there was nothing left to say.

Then Izzeldin took a deep breath, summoning up the strength as he must have to do so many times every day. A sigh heavy with loss and emotion. He turned from me and leant forward towards the audience.

“It is so, so hard. But ultimately the greatest courage is to forgive.”

This is an exclusive extract from Ten Survival Skills for a World in Flux (published by Williams Collins), out on February 3, 2022.