The day has begun at al Rams harbour before the first call to prayer has drifted across the water.

Fishermen have been hard at work for hours when the first streaks of sunlight hit the mountains over the north coast village. Yet at no point is the harbour empty. It has been the heart of the fishing village and its connection to the outside world for centuries.

"Every morning, every afternoon, every day we are here," says Ali Obaid, 36, a fisherman. "I feel it's very fantastic, very beautiful, very relaxing."

This, he says, is more than a place for boats. Cousins, brothers and grandfathers meet daily at the shacks that hug the harbour. Inside most are sitting rooms, decorated with portraits of sheikhs and pictures of horses and camels, while others are used as lodgings by Indian fishermen.

Ali sits outside with friends, surrounded by blue and green nets and circular cement weights drying in the shade. The sense of camaraderie grows as the morning passes and men return from the sea.

"This is culture and tradition," says Abdulla Ali, a 19-year-old student known to his friends as Chickpea. He can be found at the harbour most days, even though he has not fished for more than three years.

"Here, we are refreshed and relaxed," he says. "Sometimes we even sleep here."

For Nasser Ali al Tenaiji, a 40-year-old fisherman, things are not quite so rosy. He is quick to grumble about rising fuel costs - petrol prices can vary from Dh400 to Dh1,000 a day, he says - and the hardships of the sea.

"Fish come by chance," he says.

Still, the thrill of working on the water can be irresistible. Nasser admits he is such a keen fisherman that he was once arrested for chasing fish too far into Omani territory.

"He will kill himself for the fish," Ali teases. "When I see the fish there, I go," Nasser replies.

Fishing is a world of rules and regulations and Rams is no exception. Boats in the harbour will be given specific mooring spaces in coming weeks, another intrusion on the workforce.

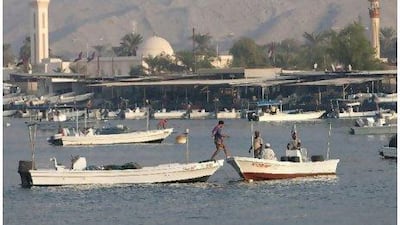

For now, though, the harbour retains its feel of happy chaos, with about 250 white boats with crooked red numbers painted on their sides. Stray dhows, greying in the sun, line the opposite beach, a reminder of the great wooden ships that once plied these waters.

The harbour contains other traces of UAE history. Mangroves and camel farms mark the north end, and on the water's surface Bangladeshi fisherman harvest tens of thousands of crusty oysters from the depths for the Emirates and Japan Pearl Cultivation and Trading Company, the UAE's only cultured pearl farm.

The harbour is about recreation as much as survival. On Fridays, families load up boats for sea bound picnics and barbecues as they remake familiar surroundings.

"All people in Rams are fisherman," Abdulla says. "Some children, some men ... maybe even some women are fisherwomen. Maybe a man will go with his wife and make a journey with his family."

Flipping through the glossy pages of a jet-ski magazine, Saled Obaid assures those nearby that fishing is not always profitable: some fishermen are forced to take loans during poor seasons.

"But I will not stop fishing," he says. "What can I do?"

Most fishermen seem content despite the vagaries of their profession. At about 10am, they receive a delivery of drinks from the corner store - a cue that it is time to set out to sea and haul in the nets.

Fantas in hand, they pile into Nasser's 40ft fishing boat. From the water, the harbour is an idyllic scene of palms, creamy minarets and tattered UAE flags.

Boats begin to gather on the sandy shore later in the day as camels plod along the beach. The nets are hauled ashore with their catch of shimmering pink and green fish, still luminous from the sea. Fishermen begin to unhook stingrays' tails from their nets and hurl each one into the water like a discus. Curious cormorants, sleek and greedy, paddle in for a peek.

By noon, the day's work is almost over and the harbour is at comparative rest. Fishermen from south India stand barefoot by their boats, coiling the nets for tomorrow. Many have worked here for decades.

"It's not an easy job, in India or here," says Adhi Easwaran, 28, a barrel-chested and balding man from Chennai. "In all the countries it's hard. But I am a fisherman. I don't know another job."