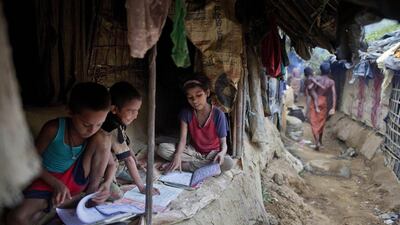

‘What must have been their feelings, the acute pains of those poor wretches, whose only crime was that of colour?” When I saw the pictures of Rohingya refugees in their rickety boats, this phrase captured my horror.

The images of their emaciated bodies, in inhumane conditions, have finally captured global conversations in a way that their persecution in Myanmar never quite managed. Yet ASEAN countries have been reluctant – I’d say repulsive – in their rejection of these dying, desperate human beings.

Mass graves have been found in Thailand. Yet the Bangladesh prime minister Sheikh Hasina described those fleeing as “tainting the image” of her country and their attitude as “mentally sick”. Hardly the words of humanity and compassion.

In Myanmar, the Rohingya Muslims face life threatening persecution, the women endure rape and humanitarian aid is blocked from reaching them. Marriage is restricted, childbirth tightly controlled. And now, even their last remaining human choice – to flee – is being forbidden.

There have also been scenes of migrants fleeing North Africa in recent weeks, with panic ensuing in the European Union where the countries, just like their ASEAN peers, are pulling up the drawbridges. The blame is on those fleeing, depicting them as subhuman.

Illegal migration is of course a huge public policy challenge in a world governed by the system of nation states. But the sheer repulsiveness of the attitudes proudly expressed about these human beings should make us stop and ask: why is their plight being disconnected from the wider context that has led to their decision to make perilous journeys?

No one wants to see their own responsibility in creating the conditions that have led to the desperation of these migrants. We blame others, rather than looking at the root causes. We worry about boats of migrants, not ethnic cleansing; about sea crossings, not war and instability. This is victim-blaming at its most shameless and flagrant.

In December 1788, the Brookes ship map was published by abolitionists advocating the end of the slave trade. It is a stark image of a ship layout depicting how African men, women and children were stuffed into inhumane conditions, with barely space to lie down, to make money for their owners. It was captioned with an iconic image of a slave in chains asking, “Am I not a Man and a Brother?” The Rohingya in their boats look eerily similar.

My opening quotation was also written by an abolitionist campaigner, a cause underpinned by seeing those different to us as equally human.

Yet today we see the same abhorrent attitudes that turn a blind eye to refugees sailing to their deaths, justified by defining a group as the “other” because of colour and ethnicity.

We pretend the root causes of their horrific experiences are nothing to do with us.

But they have everything to do with us. Just look into the eyes of those boat refugees and answer their question: “Am I not a Man and a Brother?”

Shelina Zahra Janmohamed is the author of Love in a Headscarf and blogs at www.spirit21.co.uk