True artistic greats never fade away though infirmity beckons and pandemic confines.

Already severely hampered by his own physical restrictions, Ibrahim El-Salahi was all but housebound before the coronavirus, and not much has changed since the introduction of those imposed by the government.

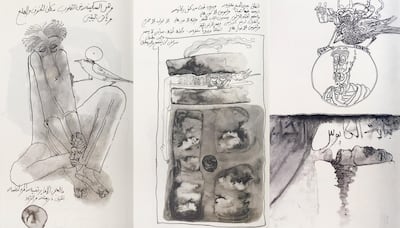

That, though, hasn't stopped the prolific nonagenarian from creating a hitherto unknown new pen and ink series of drawings from whatever happens to fall through the letter box.

Salahi has come to regard the post, whether election material from the local Oxford branch of the Labour Party or a Barclays bank statement, as just another canvas, much like anything else within the limited realm of his reach.

"Lockdown has been little different, really," he tells The National.

“Because of ill health, for some time now I’ve stayed quietly at home, thinking, meditating and sometimes creating new works.

"I've produced a number of little drawings since the first lockdown. I call them the 'Coronavirus Mask' drawings. They are an extension of my 'Pain Relief' series."

Between 2017 and 2019, Salahi embarked on almost 200 diminutive drawings to distract himself from the suffering caused by sciatica and chronic back pain.

The artworks’ size makes their creation a practical possibility in spite of his physical limitations, and he says that focusing on the miniature pieces helps him forget his afflictions for a while.

“Making these works, I go into a space where I become lost, which gives me respite from my aches and pains,” he says.

“I make these tiny drawings from the comfort of an old armchair, in pen and ink on the backs of medicine packets, scraps of paper and envelopes; things that are to hand.”

Selected drawings undergo a second transformation in scale and material. Each one, which he calls a seed or nucleus, is pressed through gauze onto a strong woven linen canvas many times over until a thick, inky texture is achieved. The final result is a substantially larger monoprint painting.

Sometimes the stamps and logos on the mail, the folds in the cardboard or patterns and indentations of the braille on the medicine packets offer inspiration. At other times, the shape of the box might remind him of things like the wooden prayer boards inscribed with Arabic from his boyhood days in Koran school.

He was born into calligraphy, as he puts it, in 1930, the son of a Sufi scholar who worked at the Omdurman Institute of Religious Studies, as well as at a khalwa for children, next door to the family home.

The future artist learned how to prepare ink and reed pens and to paint verses from the Koran. However, art was not his early ambition. At high school, he was intent on studying medicine but ill health precluded him from joining in much with the other students.

Instead, he went to the then School of Design at Gordon Memorial College in Khartoum, where he realised his direction in life.

In 1954, Salahi won a scholarship to the Slade School of Art in London, and he would spend much of his time visiting the capital’s art and cultural collections. His presiding interest was the origin of written letters, their background, structure and meaning, whether Arabic script or hieroglyphics.

He returned to Sudan in 1957, keen for his countrymen to see all that he had learnt during his three years of study in London. With an air of proud anticipation, Salahi surveyed his work - landscapes, still lifes, nudes and portraits - hanging in the exhibition hall of the Grand Hotel Khartoum ahead of the opening.

The reception was not what he had expected.

Out of courtesy, the Sudanese compatriots he invited came along, but they drank the free soft drinks and then quickly vanished, Salahi recalls.

Westerners resident in Khartoum bought the works, and further exhibitions were organised at the American and French cultural centres. But the reaction from his fellow countrymen had come as a profound shock.

Not long afterwards, he stopped painting altogether for two years, teaching for a while before taking a job at the Department (later the Ministry) of Culture. To better acquaint himself with his country’s artistic heritage and what appealed to the Sudanese aesthetically, Salahi embarked on a long road trip with his friend, the acclaimed writer Tayeb Salih.

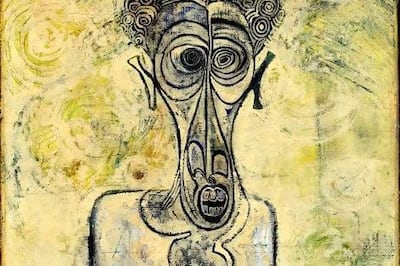

“As I saw the interior of people’s homes, I found calligraphy and Sudanese decorative patterns such as crescent moons, native animals, African masks and the veils worn by women in the Islamic north that had been preserved by local craftsmen in goods made of leather and wood,” he has said of the discoveries.

They inspired him to use calligraphy and Arabic script in his work: words from poetry and the Koran, and sayings that people were familiar with. “I started to write small Arabic inscriptions in the corners of my paintings, almost like postage stamps ... and people started to come towards me,” he once explained. “I spread the words over the canvas, and they came a bit closer.”

Finding the missing link between his work and his homeland’s culture felt revelatory, but the objects and the folkloric motifs, he realised, had been with him his whole life.

With fellow painters Ahmed Shibrain and Kamala Ishag, he founded the “Khartoum School”, the African Modernist movement that created a distinctive artistic identity for the newly independent Sudan. Its hallmark was the use of calligraphy and Arabic script simplified into abstract shapes.

The “African” label, though, rankles with Salahi. Once, in exasperation, he told an interviewer: “We’ve been neglected for many, many years, particularly in comparison to Western art and so on. People always try and push it down to ethnicity, to the tribal aspect, the village art. But never as art in itself.

"For heaven’s sake, either take us as art or leave us alone.”

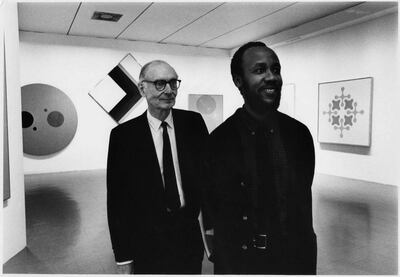

The designation pops up time and again. In 2013, he became the first African artist to be granted the honour of a retrospective at Tate Modern in London. It was, though, he conceded, good "to come in from the cold". The Guggenheim Abu Dhabi subsequently purchased Life Diary, a notebook of 83 drawings completed in the run up to the solo show.

On the day that the retrospective opened, Salahi told the BBC, “I have aches and pains of an old man but it’s a wonderful thing, to have the chance in life when you’re still alive to deliver what you have been carrying.”

His physical discomforts are the consequence of six months in prison. At the end of the 1960s, as General Gaafar Nimeiry seized power in a coup, Salahi was sent to London as assistant cultural attaché at the Sudanese Embassy.

By the time he was summoned back three years later, Sudan was a military dictatorship. He was offered the post of Under-secretary for Culture, responsible for the National Council for Arts and Letters.

Then, out of the blue on his 45th birthday, Salahi was accused of conspiring to stage a military coup, and imprisoned without trial in Khartoum’s infamous Kober Jail in 1975.

He denied the charges but recalls that “people came and beat the hell out of me. Until now, I am suffering from it.”

In what was to become a characteristic means of escapism, he drew on scraps torn from the paper bags in which his family brought him food. It had to be done in stealth - those discovered writing on paper were punished with two weeks’ solitary confinement.

When he was released, as abruptly as he had been imprisoned, he left his drawings behind, buried in the sandy floor of the cell he had shared with 10 other inmates.

Shortly afterwards, he was offered a job in Doha helping to translate and record historical documents. He accepted without hesitation, and this second period of time away from Sudan had a distinctly different flavour to the first. Salahi, in no hurry to return, stayed away for 17 years.

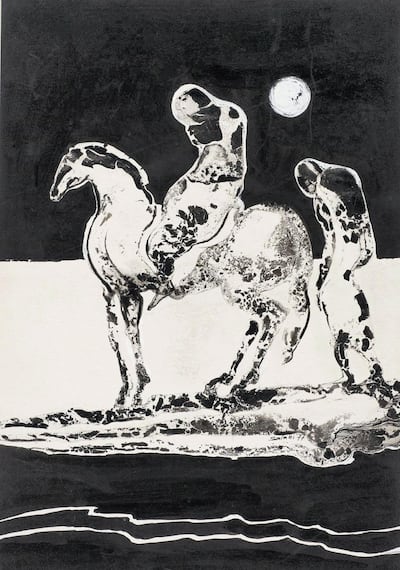

Between sending his translations to the typist and receiving them back to proofread, boredom abounded. To relieve the tedium, he recorded his Kober experiences, working in black and white in an attempt to find “the gap in between”.

It was one of his most productive, creative periods. The delicate ink drawings of cramped and shackled figures, faces behind barred doors, self-portraits, prison architecture, birds and mythological figures became the Prison Notebook, a body of work acquired through Vigo Gallery four decades later, by the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Throughout his career, birds - sparrows in particular - have featured prominently, embodying Sudanese identity and suggesting liberty or escape. As he explains it, “The bird represents a sense of freedom. I’m thinking of the people and their nomadic lives; they reject authority and they are all by themselves.”

Trees, too, are a common motif. The haraz, an acacia that grows in the Nile valley, sheds its leaves in the rainy season and bursts into bloom in the dry, reminding Salahi of the “obstinate” nature of his countrymen.

In Oxford, where he settled with his wife Katherine, an anthropologist, in 1998, he has long been intrigued by the weeping willows, and the reflections they cast in the water. The fascination led to a series called “Oxford Trees”, some of which featured in a solo show at the Ashmolean Museum in his adopted home town in 2018.

Titled “A Sudanese Artist in Oxford”, the exhibition curated by Lena Fritsch spanned 60 years of his career. With Fritsch and the Curator for Ancient Egypt and Sudan Liam McNamara, Salahi chose ancient objects from the museum’s collection, such as pottery decorated with images of the people, plants and animals of Sudan, to display alongside his work.

There is little possibility, though, these days of observing the willows. Yet, while Salahi doesn’t get out much, he has received an initial dose of the Covid-19 vaccine and awaits the easing of lockdown.

“I’m looking forward to being well enough to move around more and to see people again,” he says, not least thinking of his eight children, 11 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

He is also planning to venture out for a meal at his favourite Turkish restaurant around the corner, and for a KFC takeaway, one of life’s guilty pleasures.

Until then, there are no signs that his output is slowing down as he prepares new work for his first show in New York, at the prestigious Drawing Center in 2022.

Most days are spent in his new studio, where inspiration arises from many sources, including construction cranes in the distance or television images of refugees and the pandemic.

At the age of 90, Salahi is rightly recognised in the West and the MENA region as not only the Father of African and Arabic Modernism but as a prominent figure in the global art canon of the past century.

His paintings hang at Tate Modern, the Guggenheim and MoMA, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, The National Museum of African Art at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, the British Museum, Sharjah Art Foundation, Berlin’s National Gallery, and elsewhere.

He hopes soon to add the name of a gallery in Khartoum to the list, and has earmarked various pieces for donation once the opportunity arises.

Whichever artworks he selects for his second homecoming, he can rest assured that his Sudanese compatriots will show a deeper appreciation than they did at his debut exhibition at the Grand Hotel six decades ago.

This time, they won’t be turning up out of courtesy - or for the free soft drinks.

From opera singers to central bank governors: read all The National's Arab Showcases here