When the British Museum began hosting a History of the World in 100 Objects in 2010, it led to a touchstone of humanity.

A decade later, when the museum decided to add just one artwork to expand the canon to 101, a specially convened panel chose a collection of sculptures by Syrian exile Issam Kourbaj called Dark Water, Burning World.

It depicts miniature boats, filled with extinguished matchsticks, in a rickety convoy fleeing the tragedy of his homeland.

For Kourbaj, the boats are a selection from thousands and thousands of small objects he has created in the 10 years since the onset of the civil war.

Living in the English university city of Cambridge, he has sought to give others access to the pains of displacement and worse that wracked Syria since well before he left his birthplace in the volcanic mountains of Suweida in the mid 1980s.

Speaking to The National from his chilly studio, he expounds on the impact of the dot. The scale of the single dot makes little impression on its own but the “conversation” between many dots is what registers with the viewer.

“It is the responsibility of others to take what they see out of my work,” Kourbaj says. “My responsibility is to put something on table. I am honoured that my pieces reach beyond the boundaries of geography.

"If I am not confident of it as an artwork, I am not putting it out.”

The 12 boats are made from bicycle mudguards that Kourbaj collects on the streets as he does his daily rounds of the city. In detail, he describes the action of picking up all sorts of discarded material reminiscent of a story he tells about his uncle.

A man he never met, the uncle would go out in search of ordnance in the rugged Druze region. It was debris left over from the French era, to be dismantled and repurposed so that nothing went to waste - at least until, as Kourbaj explains it, he "sadly drew his last breath" when one of the artillery shells blew up.

“The French left Syria and they left many unexploded bombs but he dismantled them and made pots and spoons out of them,” he recounts.

“[In my childhood], I was eating with the spoons that were once bombs; the object of nurture was coming from the object of destruction.”

In the cold of the mountains, his grandmother made patchwork quilts to keep the family warm. The way Kourbaj recalls it, the quilts - the first abstract "paintings" he had ever seen - along with the pots and spoons were formative of his own art.

“If you like, a school of thought stayed with me and I didn't actually expect that,” he says.

“Our childhood is always with us. That is the compressed self. It is actually revealing itself through the years. As an artist I dig back to that place and use it.”

After leaving home at 17, Kourbaj went first to Damascus to study fine art painting and then to St Petersburg for an architecture course before arriving at Wimbledon School of Art in south London to apply himself to theatre design.

What he could not shake was his upbringing. “When I was student coming from the mountains down to Damascus, it was to a totally different geology and totally different culture," he says.

“Above this geology, there was a regime that tests you as an artist and a cultured person. You will not be a part of the establishment so you have to fight and your weapons are very modest weapons. It is a brush and it's a very vulnerable place against the tanks."

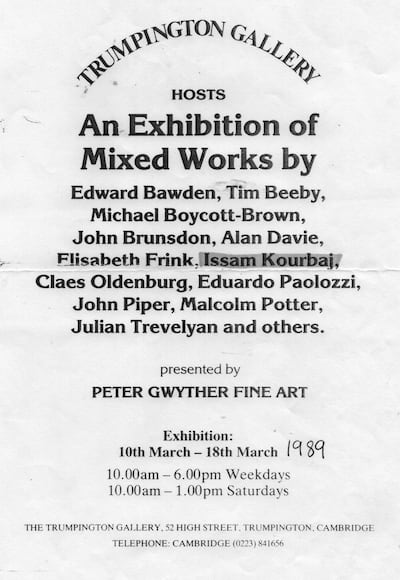

Cambridge became home in 1990 after an exhibition of his drawings went on display with some of the finest artists of the day. While fellowships and exhibitions at the great museums and libraries have followed, the quest has not always been an easy one.

“When somebody's coming from a place of destruction and oppression, they smell the smell of freedom and suddenly they have to make themselves and work hard on themselves," he says.

“I was incredibly fortunate to be offered the chance to go to Russia to read Architecture at the Academy of Art and Architecture in St Petersburg. Coming to England, particularly Cambridge, was not paved with gold for somebody who is Syrian, an artist and not speaking English.”

Inspired by the observations of solar eclipse by Ibn al-Haytham in a chamber “Albeit Almuzlim”, Kourbaj nurtured a project for years to create a spire camera obscura to crown the city’s The Great St Mary’s Church. The idea was to mark the 800th anniversary of Cambridge University through Haytham’s work on light and optics in the 10th century. When bureaucracy finally killed the plans that he had expended so much time on, Kourbaj went to a dark place.

"You have to be in the darkness to see the light, so after investing four years of my time, I fell into this long depression," he recalls. "Somebody gave me an old set of Encyclopaedia Britannica that was supposed to be milled."

Kourbaj isolated himself in his studio where he produced more than 10,000 drawings from every page in the 12 volumes in just seven months. Gradually the piece, called One+ Eleven = Two, pulled him out.

The strengths gained in that time of hardship gives him insights into the ordeals of many people during the lockdowns triggered by the pandemic. The UK is about to mark a year of intermittent stay-at-home orders that Kourbaj has followed like almost everyone else.

Towards the end of 2020, which was a leap year, he put on a display at Cambridge's Fitzwilliam Museum called Don't Wash Your Hands — a collection of 366 eye idol sculptures made from Aleppo soap. The eye idol harks back to the temples of the Mesopotamian plains 2,500 years ago.

As he began the project, he soon realised that he was merely making what looked like copies of the original ancient alabaster idols. “This is not the way I work," Kourbaj says. "The more I made them, the less satisfied I was because they started speaking to me as existing objects. I wanted them actually to reflect what's happening now.”

So he closed his own eyes and started to sculpt, wanting to remind the world not to be blind to the crisis in his homeland.

“I could see that they started reflecting something really much more vulnerable, much more about what is happening now in many parts of the world, particularly in Syria.

“This is the vulnerability of war and the vulnerability of being locked down. They started to speak to a different level when I made them blindfolded.”

Kourbaj's love of salvaging meaning from objects designed for another purpose is the common theme for his work. The boats that became the 101st object of his history will be at the heart of a new exhibition of his work called Fleeing the Dark at Amsterdam's Dutch National Museum of World Cultures slated to open in April.

Neil MacGregor, the former British Museum director and author of the 100 Objects, described Kourbaj's flotilla as standing for all migrants who are driven by fear and guided by hope.

“It is an object that can translate for us all an experience beyond words, which is both a unique event and a continuing, constant part of human history,” he said. “An object that will not only inform but move us.”

In fact, Kourbaj makes this point, too, when tracing the inspiration for the boats back to a trip in the 1990s to Cuba where he saw people in Havana take their furniture to the beach, and dismantle it to make vessels to carry them to Miami. Many didn't make it. “Making sculpture was not something I was familiar with or had worked with, but that event in Cuba and, of course, the memory of my uncle and my grandmother formed something quite magical," he says.

“I could see that I could use it as a language. What I am attracted to is finding an object that has lost its life, its voice, and, by conversing with it and working with it, I can give it a new voice."

* Tonight at 5.30pm GMT, together with writer Malu Halasa and artist Sulafa Hijazi, Issam Kourbaj will discuss their work in the new British Museum exhibition 'Reflections: contemporary art of the Middle East and North Africa', which runs until August 15