In November, a social experiment involving a woman apparently being abused in a lift went viral. Conducted by Swedish organisation STHLM Panda, which makes videos about social issues, it was designed to assess the reaction of people witnessing abuse.

Shockingly, of the 53 people who saw the violence, only one intervened.

The results of the experiment revealed the deep-rooted psychological and legal dilemmas eyewitnesses face when it comes to reporting abuse.

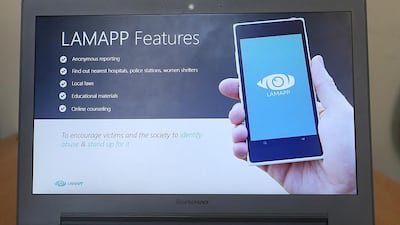

It also became the starting point for 22-year-old Heba Mahmoud Nayef, a computer-science student at the University of Wollongong in Dubai, to develop LamApp, a smartphone application that allows you to report abuse anonymously to authorities and sends a distress call to contacts.

Nayef worked on this innovative app with team members Artaza Aziz and Jawed Jandali Refai, and it recently won the World Citizenship category in the Pan Arab semi-finals of the Microsoft Imagine Cup.

The students will present an updated prototype at the finals of the competition, in Seattle next month, where they stand to win US$50,000 (Dh183,647) and meet Satya Nadella, the chief executive of Microsoft.

“The question we kept asking ourselves after we saw that experience was why weren’t people reacting to the violence they saw,” says Nayef. “Obviously, we all want to do something, but we often don’t. Our research shows people are often concerned about their involvement and legal implications. The laws aren’t always straightforward when it comes to reporting abuse, either.

“The first thing that pops into people’s minds is that trying to report abuse will get them into trouble.”

LamApp isn’t created to mimic other safety apps online because its success depends on a complete customisation and integration with the authorities governing such crimes in a particular country.

The app would have to be approved by organisations including the police, social services and hospitals to provide a complete range of services to witnesses and victims.

“There are lots of apps in the market targeting only the users, but the real issue of underreporting needs an approach where the authorities are involved,” says Nayef.

The main feature of this app is the video and audio recording function, allowing the user to discreetly record the abuse.

In the UAE, uploading videos of people without their consent is a crime but, Nayef says if the app were adopted by the police, it would address that concern.

“The audio and video can be recorded in the app and sent directly to the authorities, with no evidence left behind. You will not be able to save a copy on your phone,” she says.

Nayef says many of the students she approached to work on the app refused because they didn’t trust its success.

“The challenge is that because of these laws people sometimes can get into trouble, even if they mean well,” she says. “And that’s where we see our app being useful because they won’t be able to defame anyone by putting it on social media, they’ll only be able to share it with the concerned authorities.”

For victims who want to report an incident when they are in danger, the creators have built in a “decoy” for their safety: a handy button allows the user to disguise the app as an innocuous webpage, while continuing to record the action.

Another essential feature is the ability to alert a friend when in distress.

“You shake the phone and shout out the name of a contact you have already registered in the app and it will send an alert to them,” says Nayef. “You can add up to four contacts.”

Authorities can upload information about the law and crime to the app, along with emergency numbers and maps showing the closest hospitals, police stations and shelters. Victims will be able to have live chats with counsellors and support groups that are registered with the app.

“A lot of victims get manipulated because they are unaware of the law. Having access to that on the app will put them at ease and give them the confidence to report the abuse,” says Nayef.

The app can benefit every user and, when applied efficiently, could cut underreporting of crime significantly, she adds. At the same time it could make authorities reassess their own laws.

In January, FNC member Afra Al Basti called for a new law to address domestic violence, which involved defining the rights people have and what constitutes abuse, and training law enforcers to deal with offenders.

“Technology has advanced so much that it is being used to solve all sorts of problems around the world,” says Nayef. “But we haven’t yet applied it to create an efficient, foolproof crime-reporting method.

“Winning the competition aside, this is our main goal. To get the app out there and assist authorities in reducing such crimes.”

The team will be competing in Seattle from July 27 to July 31

aahmed@thenational.ae