London psychiatrist Dr Saleh Dhumad recalls the story of a woman in Iraq who suffered from crippling headaches. She had lost her husband in sectarian violence and her pain – strangely – was especially bad at sunset. She had taken pain medication for years, but that had failed to alleviate her symptoms, so she was referred to mental health specialists in Iraq.

"We went back to the time when she had no headaches at all," says Dhumad, who is director of the London Mental Health Group. "After her husband was killed, his body was not released from hospital for months. When she went to receive the body, the first time she looked at him was at sunset. Then we realised she had not been back to that hospital since." They believed the psychological impact of this was causing her health issues.

Dhumad, who was born in Baghdad, has worked in Iraq as part of the Royal College of Psychiatrists' international volunteers scheme and in 2009 helped to establish the first Cognitive Behavioural Therapy training programme at Medical City in the Iraqi capital. Part of the therapy he prescribed to the woman was for her to return to the hospital where she had collected her husband's body. Interestingly, her headaches stopped immediately and she was left able to grieve properly.

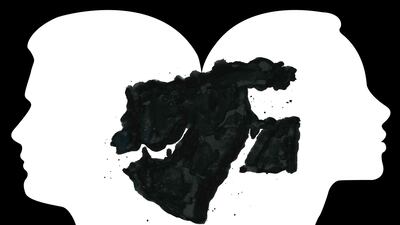

A global issue

This story, and many others like it, holds particular resonance in the region today, as well as the wider world, with mental health care having become a hot topic. This month, the US marks Mental Health Awareness Month and this week was Mental Health Awareness Week in Britain; both campaigns work to change the conversation around a traditionally taboo topic and promote healthier ways for institutions and individuals to deal with illness.

In the Arab world, it's also crucial and yet the cultural stigma surrounding psychological maladies, such as depression, anxiety and bipolar disorder, remains. "People avoid it, people don't talk about it and then the pressure falls on the kids," Ally Salama recently told The National. He started a Facebook support group in Egypt to open up a conversation among young people, and believes it's important for both adults and children to talk more openly. "It's toxic," he adds. "A lot of adults don't really realise it, because a lot of kids suffering don't talk to the people closest to them."

While the 2019 Arab Youth Survey, which was published last month, shows that people in the region are opening up about mental health issues – 31 per cent of respondents said they know someone with a condition – many others still find it a difficult subject to discuss. Reem Al Ali, one of the founders of With Hope UAE, a group that promotes mental health awareness across the Emirates, recently told The National about her struggle to help tackle mental health problems. "Even telling family that I was volunteering at a psychiatric hospital was not only difficult for me but for the other members as well," she said. "Our families didn't accept it and some of us even had to lie in the beginning about where we were going."

A history of mental health care in the Middle East

In such circumstances, it's easy to forget that centuries ago the Middle East and Islamic territories were a hotbed of medical innovation, when mental health provisions were an integral part of hospitals across the Muslim world. "The interface between mind and body was very much at the centre of medieval Islamic medicine," explains Peter Pormann, professor of Classics and Graeco-Arabic Studies at the University of Manchester. "Your mental state was one of the so-called six non-naturals – things that influence your health that are outside your body."

Healthcare institutions sprang up across the Muslim world during the medieval era and were far more advanced than anything offered in Europe at the time.

Towards the beginning of the ninth century, the earliest known hospital established by an Islamic ruler was founded in Baghdad, under Harun Al Rashid, whose domain covered what is now known as Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Iran. As more hospitals were built in Baghdad, and others sprang up in Cairo, in the mid-12th century, the Nuri hospital was founded in Damascus by Nur Al Din Zangi, the Muslim ruler of northern Syria. It became a leading light of medical care in the region and had a school, complete with a library.

Pormann, editor of 1001 Cures: Contributions in Medicine and Healthcare from Muslim Civilisation, calls these medieval hospitals "one of the great success stories of Islamic medicine". It was at pioneering institutions such as these that remedies, including music and epithyme – a parasitic plant growing on thyme – were applied for mental health disorders such as melancholy. But Iraq and Syria are different places today. The former is still trying to regain stability 16 years after the US-led invasion, while the latter has spent eight years in the grip of civil war. Understandably, conflict and political upheaval have made the medical needs of their populations difficult to address.

'We've had to rely on outside help'

Generations of Iraqis have only known violence and struggle at home. A 2018 Save the Children survey in Iraq revealed that "43 per cent of children in Mosul reported feeling grief always or a lot of the time". Yet much of the responsibility for remedying these emotional and psychological impacts has fallen to non-governmental organisations such as Medecins Sans Frontieres, which has provided welfare and support to many Iraqis with mental health ailments, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression and schizophrenia.

Dhumad has also committed to assisting the country of his birth by "building capacity" in counsellors and therapists to deal with the stress encountered by ordinary Iraqis. "I'm working with the University of Baghdad to establish a diploma in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for any health professional with mental health training," he explains. He recommends this for treating depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress, which were the main psychological disorders in Iraq, according to the 2007 Iraq Mental Health Survey by the World Health Organisation – cited as the last reliable study on the matter conducted in the country.

Syria appears to be in a more perilous state than Iraq. The civil conflict in the country has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, has forced 5.7 million Syrians to flee. Experts say the fighting has also left countless Syrians in need of psychological support. "From a Syrian context, mental health and psychology was not very developed, even before the conflict," says Dr Zaher Sahloul, a Syrian-American trauma specialist. Algeria-born Sahloul is president and co-founder of MedGlobal in Chicago, which provides free healthcare to refugees and the dispossessed in disaster zones. He has travelled regularly to Syria to practise trauma surgery. "With the war, you had a flight of psychologists and psychiatrists," he says. "So we've had to rely on training, outside help and medical missions."

Sahloul, who last visited Syria in 2017, says medical professionals have also suffered conflict-stress. "A couple of days ago I received a text from a doctor in Idlib, who is working in a hospital," he says. "But before that he was in Aleppo, under siege, and he was displaced with all the others who were displaced in early 2017. In his text, he said that he had not had a good night's sleep since then, and wakes every night with nightmares. This is typical PTSD."

Sahloul went to medical school with Syria's President Bashar Al Assad in the 1980s, and he laments the lack of services in Syria. Like some healthcare providers in other parts of the Arab world, Sahloul insists the Syrian situation is worsened by the stigma attached to admitting mental health complaints in the first place. But the consequences of allowing this ticking time-bomb in mental healthcare to go unchecked could be fatal, he says. "Many children could become drug addicts or gang members," he says. "They are also the ideal prey for terrorists because of what they have witnessed and because of their level of depression and PTSD."

Hope for the future

As long as people like Sahloul and Dhumad remain committed to providing aid in the Middle East's conflict zones, there is hope. They're also trying to build on the great initiatives being offered elsewhere in the region. Lebanon, for example, which endured 15 years of civil war, offers a model for Syria's future, says Sahloul. "Lebanon has a reasonable healthcare system and people are educated about the implications of mental health," he explains. "They direct reasonable resources to address the problem and they have mental health workers, psychiatrists and psychologists, including good numbers of child psychologists."

The UAE is also setting a regional benchmark by addressing growing concerns. In Dubai, where figures suggest about a third of the population is in need of mental health intervention, programmes designed to assist primary caregivers in diagnosing the early signs of psychological illness have been initiated.

As countries such as Iraq and Syria struggle with unrest or outright conflict, a mental health crisis continues to brew. This is not to mention Yemen and Palestine, particularly Gaza, where a WHO report last year found the blockade has had a "huge effect" on the population's psychiatric health.

While the region's centuries-old tradition of pioneering healthcare remains a proud chapter in the history books, its future mental well-being is dependent on modern initiatives that only today's caregivers and policymakers can provide.