The day before I meet Michelin-starred chef Vikas Khanna in Dubai, one of his peers, Marco Pierre White, has been making headlines for claiming that women are at a disadvantage in the kitchen because they are more emotional than men, and incapable of carrying heavy pots and pans. “The real positive with men is that men can absorb pressure better, that’s the main difference, because they are not as emotional and they don’t take things personally,” is White’s antiquated view.

I ask Khanna, a long-time proponent of equal opportunities for women in his native India, what his thoughts are on the matter. And whether this kind of thinking is still prevalent in the world’s top-tier kitchens. “Marco Pierre White has proven himself, and his opinion is valid – to him, but not to me,” Khanna responds. “One of my protégés, Aarthi Sampath, is a girl from Bombay and she cooks better than me. And I am more emotional than her. But also, if we want people without emotions, why don’t we use machines to cook?”

Emotion is the thread that runs through my conversation with Khanna. It is emotion that drives him in the kitchen; emotion that inspired him to make a film about the treatment of widows in India; and emotion that bursts to the surface every time he mentions his grandmother, whose presence looms large over Khanna’s remarkable rise from a boy with club foot growing up in poverty in Amritsar, to a celebrated chef, author, filmmaker, humanitarian and TV personality who has cooked for the Obamas and the Dalai Lama.

The world's best chai?

But first, chai. “I’m sure you’ve had chai before,” the softly-spoken chef says as we settle into the private dining area of his new restaurant in Dubai, Kinara by Vikas Khanna at JA Lake View Hotel. “And I don’t mean to sound arrogant … but this might be one of the best chais you’re ever going to drink.”

He’s not wrong. The milky concoction is delicately laced with cardamom and saffron, with a tiny pinch of salt to balance out the sweetness. It is, in its flavoursome simplicity, entirely reflective of the overall ethos of Kinara. “We are not doing a lavish menu – I don’t want 200 dishes. I just wanted to bring a very simple way of cooking dishes that we all miss. Today, there is so much anxiety in the world, so food that gives us comfort is important.”

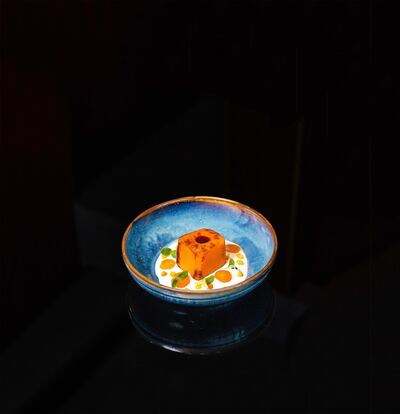

There are modern twists on classic dishes, with a strong focus on the smoky flavours of the tandoor. Examples include shakarkandi ki chaat, a sandalwood-smoked sweet potato with cumin labneh and strawberry-ginger dressing; anjari tamatar murgh, a chicken roulade with tomato-fenugreek gravy, roasted figs and coriander oil; and tawa fish, sea bass with spiced almond sauce and yellow mustard caviar.

Khanna is nervous ahead of the opening, he admits. But that’s par for the course. “I’m nervous all the time. Because you have to be. Cooking is something that’s alive. It’s not as if you make a product and it just exists there. Every day you have to start from scratch. Nature has such a hand in it – and then there is the human touch. Both are variables.”

There are plenty of variables – but also one constant in every single restaurant that Khanna has ever opened. “I will not turn on the gas until my mum comes and turns it on for me,” he explains, pulling out his phone to show me a video from the previous day, of his mother and grandmother in the Kinara kitchen conducting “a fire-lighting ceremony”. Khanna is quick to qualify: “It’s not religious. But it’s very powerful.”

Khanna attributes much of his success to his grandmother, who not only showed him how to make round breads, but also offered him refuge in her kitchen and taught him about food’s power to unite. “I was born with a club foot,” the chef reveals. “I used to be upset because I couldn’t run like other kids; the kitchen was the only place I felt equal.

“My grandmother said: ‘I’m going to teach you everything I know, but you have to understand that there has to be unification through food. People are going to have good days and bad days, but food has to provide comfort.’ In any restaurant I’ve done, I feel like yes, it’s a commercial venture, but it still retains its soul, which is what I always felt in her kitchen.”

So if he could bring any two people around a table and unify them with his cooking, who would he choose? “I would bring together the heads of India and Pakistan,” he says. “I’ve trained in both countries, so let me cook!”

Shedding light (and colour) on India's widows

Khanna's new film, The Last Color, is an ode to some of the most ostracised individuals in Indian society – the widows of Vrindavan. The film questions an ancient but existing Hindu tradition where, after the death of their husbands, women in this holy town in the North Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, are expected to forgo earthly pleasures and live out the rest of their days in worship, dressed in white, separate from society. In many instances they are believed to be cursed, and are treated as such.

“I was in this ancient city in India during Holi. There’s a temple where they celebrate this festival and I’d seen the pictures. I went there and as I was coming out, I saw hundreds of widows, colourless. I was walking by them and this guy behind me said: ‘Don’t look at them, they are inauspicious.’

“I was told that you had to treat them a certain way – I was told that they could never hold a child, couldn’t be at festivals, couldn’t touch colour, couldn’t eat food like us; that they would be condemned and punished for the rest of their lives. And we had accepted it. Everybody had. Nobody stood up to break the cycle.”

Khanna can barely contain his emotion as he explains how his eyes were drawn to one particular widow, about 90 years of age, and he subtly acknowledged her. “She was so happy. She put her left hand on her heart and looked around as if to say: I hope nobody sees me blessing you,” he tells me. “I felt like I was in a coma and I woke up. She was ashamed to bless me because she knew people would tell her to get out of the way, or tell her not to look at me. She had accepted being less.”

So Khanna wrote a story about being “colourless”, and turned it into a movie that is currently doing the rounds at film festivals around the world. “I felt like I was in so much debt because of that blessing. I couldn’t just let it pass. So I made the movie – and I got India’s best actress [Neena Gupta] to star in it.”

The plight of peppercorns

The chef is great a supporter of the underdog. Even when we discuss ingredients, he laments the misfortune of red and green peppercorns, which are so often overshadowed by the black variety. "One guy became so famous in the family that no one remembers the others," he says with a laugh. "People just don't realise the amazing beauty of red and green peppercorns. So I request that whenever people are creating their little spice mix, they should put different kinds of peppercorns."

Other favoured ingredients are mulethi, or liquorice roots, and salt, which he also views as grossly underappreciated. “There are so many different varieties of salt and so many different tastes. It’s an ingredient that is always there. It’s like parents, always there, but when they are not there, you miss them. You take them for granted."

From $3 curries to cooking for the Obamas

After his early apprenticeship at his grandmother's side and in the community kitchens of Amritsar's Golden Temple, Khanna attended the Welcomgroup Graduate School of Hotel Administration in Manipal, before moving to New York, where through sheer grit and determination ("poverty teaches you everything – you become so strong and multifunctional"), he ended up starring on Kitchen Nightmares with Gordon Ramsay, became one of the first Indian chefs to earn a Michelin star, cooked for presidents and authored 34 books, including Utsav – A Culinary Epic of Indian Festivals, the most expensive cookbook in the world.

“I used to sell food for $3 [Dh11] on Wall Street,” he recalls. “That would include one curry and one rice, or you could opt for one bread.” In 2012, he prepared the food for an event hosted by the Obamas that cost $39,500 per head. “President Obama made a big contribution towards my career and growth in so many ways, because he was always such an admirer of Indian food and was such a cultural influencer. I cooked for them many times. You’d never expect an Indian chef to be invited to cook at the First Lady’s birthday at the White House.”

He is less complimentary of the current president. In the future, he hopes to turn his filmographer's eye to the issue of immigration in America – to use his influence and platform in the public sphere to counter what he sees as bullying at the very highest levels of politics. "There are so many people around me that have not had the same opportunities as me. There are things happening in that amazing, historic White House that influence families on such a minute level. We are giving permission to bullies. I remember how bullies crushed my self-confidence and instilled so much self-hate in me. And now people are just accepting that as normal."

His voices crackles with emotion once again – and I, too, am almost overcome. “I spent 30 years, using a different craft, rising above bullies. And it feels like I’m being thrown back in the dirt when I see people in the top offices on the planet speaking like that. If I keep quiet, I feel like I am silencing the woman who stood for me when the entire world did not. My grandmother would say: ‘Ah, don’t worry about those bullies. They’re just jealous of you, because you can make a round bread.’ She had to find something positive in me. And that’s what she found.

“People used to say to her: ‘He’ll never have proper legs.’ And she would say: ‘Oh no, don’t worry about it. He was never born to walk; he was born to fly.’”