A sizeable chunk of the technology industry considers our reality to be a bit dull, and has devoted itself to altering, bending or replacing it.

From the total immersion of virtual-reality headsets to the merry world of Snapchat stickers – where faces are appended with animal ears and whiskers – there is a blurring of the line between what is real and what isn't, fusing the virtual with the actual in an ever-more-convincing way.

In recent days, there has been a buzz of excitement about one strand of experimentation known as augmented reality, or AR.

Apple invited the press to its headquarters in Silicon Valley to show off a collection of AR apps that will run on its new iOS system software, expected to be released on Sept 12, while Google just announced the launch of ARCore, a kit for developers to make AR apps for Android devices.

It heralds an era when our smartphone cameras become a window through which we see real and imaginary objects realistically combined: computer-generated trees, trucks and tortoises appear for all the world to see as if they are actually there, while animated fictional characters line up alongside our friends.

Some commentators see AR as such an important development that they refer to it as the eighth mass medium, taking its place in line after print, audio recording, cinema, radio, television, the internet and mobile.

These developments don't happen overnight, and there have been many precursors to the imminent AR wave.

Google's controversial spectacles, Google Glass, launched in 2013, offered a form of AR, where information was projected on the lenses to be visible by the wearer.

Microsoft's HoloLens was unveiled in 2015; described by the company as a "mixed reality" holographic computer, it displayed apps such as Skype and Minecraft "in-vision" via a wearable headset, and received many positive reviews.

But the apps coming our way will be mediated via our phones; no bulky headsets to worry about; no anxiety about whether the technology is socially acceptable. Phones are ubiquitous – if we are going to be persuaded that AR is worth engaging with, it will be phones that do it.

Snapchat has already dipped its toes in the water. The World Lenses feature of its photo-messaging app lets you choose objects from a palette and drop them into the scene you see through your camera. These objects aren't simply overlaid – they effectively become part of the scene, getting bigger as you get nearer and smaller as you move away.

It is unusual and fun – but it takes more than unusual and fun to spark an app revolution. Practicality and usefulness are the boxes that need ticking. The question is whether the new set of AR apps will do so.

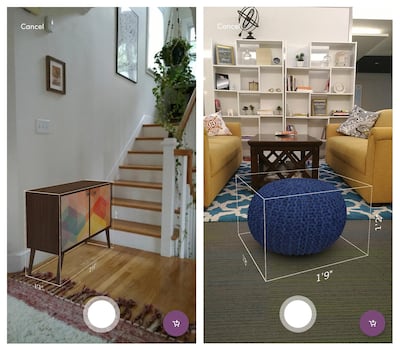

The app that has received the most attention is Place, designed and built by Ikea. After choosing from the 2,000 items in its catalogue, you use the camera to hover, rotate and place pieces of furniture in the room you would like to see them in, giving an indication of what they will look like in situ.

Ikea's lead was followed by Toshiba, whose AR app does a similar thing, but with TVs. While useful in theory, these applications will have to establish a level of trust in users before we completely dispense with the old-fashioned tape measure.

A simpler, more engaging app is Neon, which describes itself as "the world's first AR social networking app". It allows you to "drop a neon" at a particular location, effectively erecting a large neon sign your friends can see through their cameras. This might seem frivolous, but if you're trying to find that particular friend in a crowd of people, its usefulness becomes immediately apparent.

As with any new wave of apps, many are built simply because they can be, rather than because they serve any real purpose. One social-media app claiming to ride the AR wave, TaDa Time places avatars of users in real-world contexts. The publicity blurb asks: "Have you ever imagined yourself hanging idly from the Empire State Building?" It is a question to which the answer, for most of us, is "no" – but other apps, from virtual car showrooms to dentistry apps that let you see the smile that could be yours, give exciting glimpses of the kind of AR interaction that awaits us.

The technology that enables all this is complex. Sensors and algorithms detect the motion of the camera as it tilts and spins, with an understanding of the surrounding environment, particularly horizontal surfaces. After all, if AR objects are to be displayed realistically, they need to obey laws of gravity, rather than hover in mid-air.

They also need to be lit the same way and cast realistic shadows. These challenges don't just place a burden on those writing the code, but they also put the phone's hardware through its paces, and it is likely that optimal display of the more-advanced AR apps will only be possible on the newest handsets, such as the forthcoming iPhone 8 and X or Sony Xperia XZ1.

__________________

Read more:

Facing the future: virtual interior design reality in the home

The reality behind augmented reality is that it’s overhyped

Sorry Oculus, but virtual reality’s popularity is still futuristic

Who can recall life without iPhone?

__________________

But even if we are equipped with these phones, will we be keen to change our behaviour? The success of Pokémon Go demonstrated that large numbers of people are willing to run around parkland with phones held in front of them, but it will never be a natural way of moving about. It could well be that spectacles are the best way of delivering AR content, but until they become more socially acceptable, it will be smartphones that we turn to.

The neatest AR apps in Apple's showcase are games. The Walking Dead: Our World sends you into the neighbourhood on a zombie-vanquishing mission, a kind of bloodthirsty Pokémon Go.

At the other end of the scale are simple, delightful games such as My Very Hungry Caterpillar, or Arise, where a ruined building is magically constructed on your kitchen table and a plucky adventurer guided around it.

The tools that have been provided to developers by Apple and Google are immensely powerful, and the possibilities afforded by them literally infinite. It is now up to creative minds to devise the killer apps that will make us want to augment our realities in ways we never previously imagined.