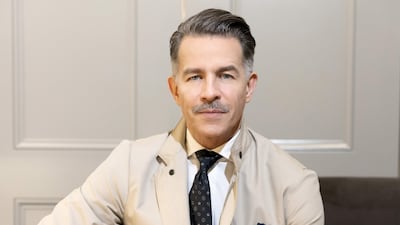

Since taking the helm as Dunhill’s creative director in April 2023, Simon Holloway has presented only three collections, but he has already defined a casual elegance rooted in decades of craftsmanship and savoir faire. Rather than chasing trends or seasonal “newness”, Holloway embraces “timelessness and classicism”, delving into the gentlemanly essence of Dunhill.

“It’s the pinnacle of an English expression,” he says, “through everything from the cloth to the cut and proportion. The incredible, rich story of Dunhill is a beautiful one to retell season after season.”

Founded in the 1890s when Alfred Dunhill inherited his father’s leatherworks, the house quickly pivoted to serve a new kind of customer. Anticipating the impact of Benz’s 1886 Motorwagen, Dunhill began making car coats, luggage, dashboard clocks and even tobacco and lighters for the emerging class of wealthy motorists.

Today, while the brand is synonymous with refined British tailoring, “Dunhill was not born on Savile Row”, Holloway notes. “It was born in the idea of motoring and then went through this evolution. It always kept with the times and had relevance to the man of whichever era it was.”

When he arrived, Dunhill had lost its footing – out of sync with modern menswear, its traditions seen as dated. Undeterred, Holloway doubled down on what makes it unique: connoisseur-level tailoring and a singular Britishness. “Dunhill is for the Anglophile. European brands have a uniquely Mediterranean taste and look, which is wonderful, but it leaves the space open for Dunhill to express its Britishness.”

That space is both elegant and rakish. “English taste can appeal to two completely different types of people,” he says. “The suits King Charles wears are very similar to those worn by Bryan Ferry and the late, great Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones. It’s the same man, whether you’re rock or royalty. One is diplomatic-level coded clothes, the other has the nonchalance of a rock star. That’s just so cool and where does that exist in the world? Only in England.”

Dunhill’s deep ties to heritage manufacturing underpin this studied ease. “We work with the last Jacquard silk-weaver in England, the last table-screen-printing mill in England, the heritage camel-hair specialist in England and many others.”

To suit modern life, Holloway has in some cases halved fabric weights, creating lighter, softer materials. “That can be everything from flannel to a gun club check that would traditionally be tweed, but now is made in a really refined, superfine merino.”

Having produced its suits in Italy for more than 40 years, Dunhill also benefits from Italian expertise, rendering jackets, overshirts and coats lighter still. The autumn/winter collection looked to the 1930s English Drape – a distinctive jacket cut devised by the Duke of Windsor and his tailor Frederick Scholte. Holloway modernised it by removing the shoulder pads and holding the silhouette through the canvas wrapped over the shoulders.

Despite such innovation, the house remains committed to “the vernacular of British cloth, texture, colour and pattern”, now reimagined in lighter constructions. The result, Holloway says, is “invisible innovation that you really feel when you wear the clothes”.

Each piece is meticulously crafted. A charcoal-grey jacket is made from suede bonded with cashmere; a field jacket from undyed virgin wool flannel is lined in merino checked tattersall. An archive double-breasted coat is reworked in wool-cashmere twill windowpane check and lined in superfine merino, while a Balmacaan coat – traditionally rough wool – is cut in houndstooth cashmere. Evening suits come in Italian dupioni silk, paired with topcoats in double-faced cashmere.

Reframing the modern wardrobe around casual elegance, Holloway lightens camel-hair coats to a shade of oat, while the single-breasted Bourdon jacket (named after Bourdon House, Dunhill’s luxury space for men in London) arrives in half-lined herringbone flannel, cut with an English sloping shoulder. A Chesterfield coat is made from natural-coloured double-faced merino wool with a windowpane-checked interior.

Even the original Dunhill Car coat has been updated in suede shearling, double-faced lambskin, or a cotton-and-silk Prince of Wales check finished with horn buttons. “The combination of these innovative lightweight fabrics made with a very heritage taste, and the lighter-weight construction gives you a more contemporary product.”

The new approach is attracting younger clients drawn to Dunhill’s quiet sophistication. “There’s a generation of men who were never told to wear a tailored jacket or a tie, and who are choosing it because it feels like an interesting way to express themselves. The whole thing is so radically chic because it’s unnecessary.”

Sliding into a well-cut pair of trousers, a soft knit, a chambray shirt or a timeless jacket, Holloway says, is about “the joy of getting dressed. Sure, sometimes you want to throw on a hoodie, but then other times you want something a little more exciting in your life.”

He gestures to a long leather coat on a mannequin in the brand’s new Dubai Mall store. Heavy enough for the British winter, lined in camel hair and burnished to a deep toffee tone, it looks fresh off the runway – yet it’s an Alfred Dunhill original Car coat from around 1905.

Its quiet beauty encapsulates Holloway’s vision. “We’ve really worked to develop a more casual, elegant side to Dunhill,” he says. “This is not about being a fashion brand. This is very much about being timeless, with a more sensitive take on masculine dressing, but still with refinement and a celebration of English dress codes.”

FOLLOW TN MAGAZINE