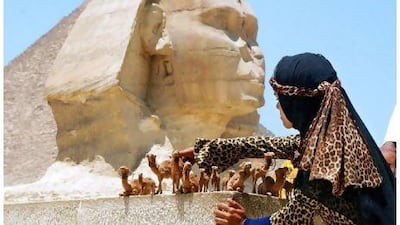

The first time it happened was in Egypt. I walked out of the Pyramids of Giza, dying to buy a souvenir. My mother had specifically asked for a miniature sandstone pyramid inscribed with hieroglyphic writing. She said it attracted positive energy and wanted to keep it by her bed. I was determined to take one back for her, perhaps two. I wanted to buy several other souvenirs for all my friends. I was, in other words, an easy sale.

The minute I came out of the pyramid area and into the tour bus car park I was confronted with a sea of vendors, all rushing towards me, entreating me to buy their King Tut toys, miniature pyramids and Egyptian shawls. Overwhelmed by the hustling, I walked straight into my tour bus, buying nothing.

The next time this happened, in Turkey, I went one better. I caught hold of one of the teenaged boys who surrounded me in Basra, holding out strands of pearls, small hanging tapestries and blue pendants that would remove the evil eye. "Abdul," I said, "instead of rushing towards every person that gets off a tour bus, why don't you wait in your shop for them to come to you? I think it will give you better business."

Abdul's sharp black eyes digested what I said. "Look," I continued persuasively, "when you rush towards me, I distrust you immediately. But when I come to your shop of my own free will, I am more inclined to buy your goods."

I mimed the aggressive hustling of the vendors, grabbing arms. "Tourists hate this," I said. "They are intimidated when all you kids rush at them."

"OK," said Abdul, "I can stop running towards you, but what about the others?"

When I didn't reply, he said: "If they run towards the tourists and I stay in my shop, I will lose the sale."

Herein lies an example of a market failure. My husband is an ardent free-market capitalist who believe that markets will self-correct. When I wanted to buy an electric car in Bangalore, he argued against it because there were only a few electric vehicles on the streets of Bangalore. "Listen to the markets," he said. But markets are not always right; and sometimes they don't know how to self-correct. Consider my own example of a market failure, epitomised by all those nameless souvenir vendors who rush towards you when you visit the Taj Mahal, Great Wall of China, the Grand Mosque or Angkor Wat. Tourists want to buy souvenirs; the vendors want to sell their products. Yet it is an incredibly inefficient system. Most visiting tourists buy less than they want to. Why?

John McMillan, the Stanford economist, would say it is because the souvenir markets are not transparent. In his book, Reinventing the Bazaar, McMillan says: "The level of ignorance about everything from product quality and going prices to market possibilities and production costs is very high, and much of the way the bazaar functions can be interpreted as an attempt to reduce such ignorance from someone, increase it for someone, or defend someone against it. Prices are not posted for items beyond the most inexpensive. Trademarks do not exist. There is no advertising. Experienced buyers search extensively to try to protect themselves against being overcharged or being sold shoddy goods. The shoppers spend time comparing what the various merchants are offering, and the merchants spend time trying to persuade shoppers to buy from them."

On his recent visit to India, Barack Obama, the US president, frequently said knowledge was the currency of today's world. It could apply just as well to tourist spots. "The search for information is the central experience of life in the bazaar," said Clifford Geertz, the anthropologist. It is "the really advanced art in the bazaar, a matter upon which everything turns".

There is a solution and it lies in Horace Greeley's edict: Go West, young men. The tourists towns of the West are havens compared with eastern bazaars. Whether you want to buy cuckoo clocks, crystal, chocolate, Delft porcelain or dirndl dresses, you can do so with ease all over Europe and the US. You walk down a line of shops, ducking in and out, examining the merchandise and the posted prices. No one bothers you; there is no hard sell; your hackles aren't up. What you see is what you get. At some point, you decide you want to transact and do so without any coercion. There might be some bargaining but very little. The whole thing is organised, civilised and without pressure to buy. As a result, more goods get sold.

Why not duplicate this in the East? What if all the women who sat in stalls outside the mosques of Isfahan, selling beads, dresses and bric-a-brac got together and decided on a plan of action? Rather than rush en masse at every foreigner and aggressively try to outbid and outsmart each other, they would work in tandem. They would get together and decide on a price for each item and post these agreed-upon prices. They would not undercut the other person's sale just to make one of their own. They would, in other words, co-operate to get out of the tourist version of the prisoner's dilemma.

It would benefit everyone: the tourists who would then be free to wander, choose and buy without being harassed by vendors. It would help the vendors, because, freed from the hustling, the tourists would probably buy more souvenirs. I know that I would have bought several miniature pyramids in Egypt were I not so wary of the vendors. Why don't eastern vendors realise this? Why don't the well-travelled tourism officials in the governments of India, China, Iran, Turkey and Egypt realise and institute this coalition of souvenir sellers? Not only would it help to sell more Arabian camels, miniature pyramids and marble Taj Mahals; it would make the entire experience more pleasant for tourists, who would come back for more.

Shoba Narayan is a freelance journalist based in Bangalore and the author of Monsoon Diary