South Africa’s economy, Africa’s second biggest, contracted 3.2 per cent in the first three months of the year, the largest quarterly drop in a decade, sending the rand plunging as unplanned power cuts and poor harvests took their toll.

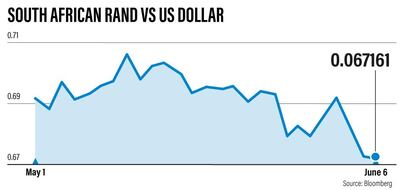

The rand shed 3 per cent against the greenback since Monday, after the country’s national statistics agency Statistics South Africa (StatsSA) released dismal figures that showed the main contributors to the gross domestic product contraction are manufacturing, mining and agriculture.

In an unusual move, the government’s economic analysts used more forceful language in their assessment.

“It’s a clear function of maladministration, corruption, malfeasance and all the structural decay it has bred. Sad to see the degradation,” George Glynos from ETM Analytics said on Twitter.

Much of the blame fell on the country’s troubled energy utility Eskom, which implemented rolling blackouts beginning in February, or “load shedding” as it is typically described.

A judicial hearing is currently underway that is slowly unpacking the widespread corruption at Eskom that resulted in flagging coal supplies and breakdowns in power plants. The unreliability of the state-owed utility has resulted in wide-ranging disruptions to key sectors of the economy.

“The concerning issue is the GDP contraction is across the whole value chain,” said Isaah Mhlanga, chief economist at Alexander Forbes investment group in Johannesburg. “It’s not just the result of power cuts, it’s an issue of economic mismanagement, which has meant fixed investment is not forthcoming.”

As a result of concerns regarding policy positions but also lack of confidence in the country’s leadership, the private sector was not investing in the economy, he said. “The investment sector needs a change in how the leadership of the country approaches economic management.”

Economists point to policy uncertainty, such as the debate to abolish private property amid a socialist push, and talk of ending the independence of the reserve bank as souring foreign capital on the country persists.

Private property ownership is currently protected by the country's constitution but some in the governing ANC party, as well as opposition parties want the relevant clause removed. A rollback of land ownership laws could allow the state to seize property without compensation or even wholesale nationalise land as Zimbabwe has over the last two decades.

“It’s very important to commit to policies that are investment friendly,” said Ian Cruikshanks, an independent economic analyst. “That way we’ll find the investors of the world will commit their capital to the country for growth potential.”

The GDP drop will also make it difficult to achieve a projected economic growth rate of 1.5 per cent, a target already regarded as anemic. The country is also struggling with record high unemployment of almost 30 per cent, and a youth jobless rate closer to 70 per cent, according to StatsSA.

The government of president Cyril Ramaphosa needs a higher growth rate if the unemployment rate is to come down. He has been trying to lure international investment though a series of road shows, and distancing his administration from the radical policies pursued by his predecessor Jacob Zuma. However, Mr Ramaphosa’s sales pitch of a business-friendly South Africa is taking time to convince skeptics.

“The problem is these things take a really long time to unwind,” says Vusi Thembekwayo, a Johannesburg business entrepreneur. “Once people start sitting on money and not putting it into the supply chain, it takes a really long time for them to start investing back into the market.”

There may be some relief in next quarter’s figures. Part of the GDP decline was attributed to a poor grain harvest in summer rainfall areas. However, good rains in the Western Cape during the winter growing season will improve agriculture’s performance considerably in the next set of figures. A boost in GDP will also help the country escape a recession, which requires a decline in two successive quarters.

“Second quarter GDP will show a significant bounce simply because of the low base set by the terrible first quarter figures,” said Wayne McCurrie, head of wealth and investments at First National Bank in Johannesburg. “So, no technical recession.”