Google searches for “commodity supercycle”, which went quiet after oil prices collapsed in late 2014, have shot up since December. As Brent crude prices breach $70 a barrel for the first time in over a year, and copper prices top 10-year highs, traders, investors, drillers and miners have begun to whisper about a new gold rush.

Commodity supercycles are usually driven by the collision of rapid industrialisation in big economies with supply-side constraints after long periods of underinvestment.

Such episodes include the post-war boom in the US, Europe and Japan in the years up to 1973, then China's boom between 2003 and 2014. Despite the different impact of factors such as Middle East conflicts, mine strikes and droughts, the prices of all commodities – fuels, metals and agricultural goods – soar in synchrony.

So, what argues against our being in the early stages of a supercycle?

Firstly, much of the recent price increases reflect a recovery from the nadir of last March under coronavirus pandemic lockdowns. Platinum, silver, copper and cotton have all doubled since then. Economic stimulus programmes in the US are helping to drive demand, but for how long?

Secondly, the gains are not synchronised and reflect differing underlying factors for each commodity. For fuels, the recent jump in oil prices has been due to the discipline of Opec+’s production cuts and a recovery in demand from last year’s lows, while the physical crude market is still relatively weak.

Refining margins remain below those of 2019, indicative of a system still well below capacity.

The producers’ group may take more than a year to unwind its cuts, during which time high prices could encourage a return of US shale and other non-Opec output. Electric vehicles are rapidly gaining on petroleum in terms of performance, market share and government policy support.

The gas story is better because of the need to replace coal for environmental reasons. China, already the world’s biggest gas importer, wants to double the share of gas in its energy mix to 15 per cent. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s target is for gas to quadruple to a quarter of his country’s energy basket.

Meanwhile, the outlook for coal itself is poor as it increasingly loses competitiveness against gas and renewable energy and is excluded from financing because of its voluminous carbon dioxide emissions.

Thirdly, supercycles need a global macroeconomic story behind them. Geographically, it is hard to see where a surge similar to China’s in the early 2000s will come from.

Chronologically, only seven to twelve years separate us from the last supercycle, compared with the two decades it normally takes before the surplus capacity of the previous boom is wiped out.

The Chinese economy remains enormously influential and the leading global consumer of most commodities. But reports presented at the current Two Sessions, the country’s major annual political meeting, point to a growth target of 6 per cent, well below International Monetary Fund projections of 8 per cent. The era of hypercharged expansion appears to be over.

Today, India’s economy is about the same size as China’s was in 2006. Its economic growth in the reform period after 1990 has ranged from about 4 per cent to 8 per cent annually. Growth was 4.2 per cent in 2019 – strong but not matching the Middle Kingdom’s sustained double-digit surge.

It is also much less commodity-intensive, consuming only a third of the coal and steel, two thirds as much oil and half as much electricity as China at the same level of GDP.

Excluding the more wealthy and slower-growing Thailand and Malaysia, the rest of emerging South and East Asia is equal to about nine tenths of India's economy and seven tenths in population – certainly a huge energy market, but again not likely to show long-term synchronised high growth.

The economic output of Africa's 54 countries is about the same as India's GDP, and so too is the number of people. However, African countries range from the relatively developed Tunisia, South Africa and Botswana or fast-expanding nations such as Ethiopia to troubled, poor and isolated states.

So, what could drive a supercycle? Climate change demands a reshaping of the global economy that is more profound than when the first settled communities began to farm, faster than when the first steam train bustled down to Darlington, England, and more disruptive than when Ray Tomlinson first emailed himself in 1971.

Entirely new commodities and those that were mere curiosities before – such as hydrogen, ammonia, carbon dioxide, lithium, nickel, cobalt, neodymium – are emerging as key components of a new economy.

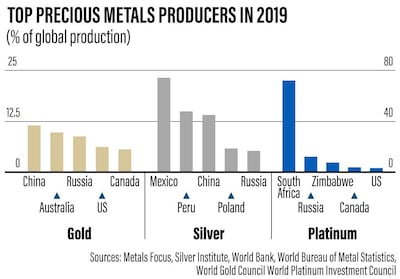

Raw material costs become increasingly important as the price of new energy systems approaches the cost of their inputs. Silver now accounts for 10 per cent of the cost of a solar module. Solar panels, electric car batteries, wind turbines, heat pumps, fuel cells and the rest of a low carbon economy demand much greater quantities of exotic materials.

Even more familiar metals such as copper are required in abundance for electric vehicles. Lucky miners and resource-rich countries will enjoy windfalls, and supply bottlenecks will hamper the new climate-friendly economy at times.

But are these materials enough to drive a supercycle? Hydrogen might be a $700 billion business by 2050, according to BloombergNEF, while lithium is today a market of less than $3bn and copper a $200bn industry. Compare that to iron ore today at $500bn or oil at $2.2 trillion annually.

Moreover, new technology can quickly displace materials that seemed indispensable.

So, there may be two wheels turning within a future supercycle: traditional materials, which speed up in the short term before winding down, and new energy components that must spin ever faster to keep up with demand. The commodity engine driving the new world economy will be a complex machine.

Robin Mills is chief executive of Qamar Energy and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis