Nestled in the heart of Chelsea, beside the River Thames, is the Chelsea Physic Garden. It was founded by the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries in 1673 to enable its apprentices to study the medicinal benefits of plants.

Although this extraordinary garden’s practical medical applications have now ceased, its collection of about 5,000 edible, useful and medicinal plants continues to be expertly curated. Visitors to the 1.5-hectare site are taken on a journey of learning and discovery that celebrates the beauty and importance of plants across continents and ages.

When Nick Bailey joined as the head gardener in 2010, he considered the role “just the perfect thing”. “It is a beautiful garden, and also has a true educational purpose to it. Part of my background is that I taught horticulture for five years, and I always felt that this had great depth and worth to it, as it wasn’t just about aesthetic horticulture.”

Shortly after taking up his new position, the chair of the advisory committee asked Bailey if he had any big visions for the garden and ideas he could bring along to the advisory council, which was meeting a couple of days later.

“I did a very, very rough sketch as I thought it was about just having a quiet chat with him; then he announced that he had this new master plan and sent me downstairs to photo copy it for everybody. It was very broad sweeps, and extraordinarily they signed it off there and then. That is essentially what has led all the development we have done here over the last six years.”

Bailey’s first challenge was to define the collection, and make it clear to visitors where various collections began and ended, and what their functions were. “The medicinal quadrant still had a plant collection, but it had shrunk to about 1/8th of an acre [0.05 hectares], which struck me as crazy given that our history is all about medicinal plants,” the horticulturist explains.

The starting point was to expand that collection and dedicate an acre to it. “With our increasing visitor numbers [55,000 annually], it was an opportunity to spread people throughout the garden and reintroduce the intimacy the garden has, while also making the collections both physically and intellectually accessible.”

The Useful Plants section was expanded, and now features such genres as dye plants, used to colour fabric, and fibre plants, which covers everything from rope-making to cotton and sheets.

A newly created Arts Bed showcases plants used directly in the creative arts, and there are examples of the first gramophone needles made from plant spines.

“We created a Land Restoration Bed, which are species that are good at being used on ground that has been damaged by chemicals of industrial use, or by nuclear waste or explosion. The Chernobyl area was cleaned by growing sunflowers, which are able to bioaccumulate a lot of the nasties and nuclear isotopes from the soil, turning it back into usable land again. The whole plant has to then be processed and taken away, which is done over several growing cycles.

“Atriplex, or saltbush, along with Beta vulgaris, or sugar beet, are able to accumulate salts in an area that has had excess nitrification or a sea flood on to it, and bioaccumulate those and turn the land back and make it usable again.

“There are also beds dedicated to housing, which have everything from the ‘Red Baron’ grass – its seed heads are used to make pillow stuffing in Japan – through to some of the key construction trees, such as the giant redwood.”

The Hygiene and Cosmetics Bed showcases traditional plants used for cleaning, such as Saponaria officinalis, or soapwort, which was used to clean the Bayeux Tapestry, through to the Mediterranean family of Lamiaceae, which includes lavender and rosemary, as the scents are commonly used across a range of household cleaning products.

“The Science and Research Bed features plants which have inspired or been used in scientific innovations, for example bamboo, which was used in light-bulb filaments before [tungsten]. We also grow burdock, which inspired Velcro, and we grow Brassica, which is the only plant in the world which has a fully mapped DNA, so it is effectively used as a lab rat for all kinds of experimentation.

“A perfumery amphitheatre contains most of the ingredients for modern perfumes and aftershaves, although there are a couple of tropical things such as Cananga odorata or ylang-ylang, which is the scent for Chanel No 5, that can’t be grown there as the English climate won’t support it,” Bailey says.

There’s also a new edible garden, which is quite different from your standard vegetable patch, because it features vitamin beds in the centre with plants that are rich in vitamins A, B, C, E and K. Superfoods also make an appearance, including kale.

“We also have a bed dedicated to plants that produce cooking oils, unusual fruits, unusual vegetables, and a herbs, spices and flavourings bed, as well as a tiny miniature vineyard, which gives a chronological history of the development of viticulture, taking you through about 15 different cultivars, starting with Muscat of Alexandria, which we believe is the earliest one recorded.”

The first bed in the medical garden is illustrative of the plants that the apothecaries would have been growing at the time that the garden was founded in 1673. “Interestingly, a good 50 per cent will kill you, 25 per cent do absolutely nothing, and there is about 10 per cent and a few oddities in between that have made it through to modern pharmaceuticals today,” Bailey says.

Meanwhile, the Garden of World Medicine is a geographical guide to the traditional medicinal plants of different regions around the world, including a section on the Middle East.

At the other end of the spectrum, the Pharmaceutical Garden features plants used in modern pharmaceuticals, so each bed represents a particular discipline. This presents the gardeners with practical challenges, because the groups have to thrive from a garden-design point of view, but they’re working with a restricted palette that you wouldn’t ordinarily group together. Areas covered here include oncology, anaesthesia, analgesia, rheumatology, cardiology and ophthalmology.

The most exciting and beautiful element in the oncology bed is the Madagascar periwinkle, or Catharanthus roseus, which yields chemicals effective in the treatment of childhood leukaemia. Taxus produces docetaxel and paclitaxel, which are both used in a variety of oncology treatments.

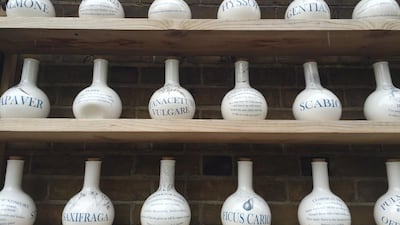

Detailed displays within the garden offer further information. “We wanted to get this multilayered interpretation, with the ‘Harry Potter’ effect, of little cupboards to open with sample medicines and write-ups of applications. It is meant to [look like] little medicinal chests, so that children can get the fact this is medicine related to the plants around them,” says Bailey.

The final stop of our tour takes us to Future Medicines, which features plants that have just been licensed or are currently being investigated, such as tobacco plants, which are pivotal in producing the Ebola vaccine.

It can take 10 or 20 years for medical research to bring new plant-based medicines to the market, yet the garden’s collection provides a fascinating chronicle of man’s inventiveness when coupled with nature’s cleverness.

weekend@thenational.ae

The garden, cafe and shop are currently open Tuesday to Friday, Sundays and bank holidays, from 11am to 6pm. For details of guided tours, walks and workshops on specialist topics, visit www.chelseaphysicgarden.co.uk.

Green Spaces is a series that features notable gardens and public spaces from around the world.

Follow us @LifeNationalUAE

Follow us on Facebook for discussions, entertainment, reviews, wellness and news.