When he launched the fifth Abu Dhabi Film Festival (ADFF) last week, executive director Peter Scarlet admitted, "The festival is always skating on the edge of disaster ... but hopefully avoiding it and hopefully distracting your gaze from it."

With more than 400 industry professionals attending, 179 films from 49 countries, including 25 world premieres and 12 international premieres, and masterclasses and seminars spread across 10 days, staging and managing such a festival is a difficult undertaking. However thrilling the ride, there can be little doubt that Scarlet and his team will breathe a collective sigh of relief when the festival reaches its final destination tomorrow and everybody can go home.

"Home," for the best part of the last few days, has been the Fairmont Bab Al Bahr. It is here, in the meeting rooms and suites, lounges and restaurants, that the business of the film festival takes place. To an outsider it is a largely impenetrable world - an amorphous mass existing under the heading, "The Film Industry." In reality it isn't so much an industry as a string of relationships, overlapping, forming and reforming, breaking down and changing shape. "A festival," Scarlet explained, "is not just about deal signing it's about the birth of relationships. We get to know each other. Sometimes films come out of it. Sometimes friendships come out of it. Sometimes miracles come out of it."

***

Shortly after 1pm the atmosphere in the film festival media lounge is one of calm. Through in the ballroom lunch is being served to the smattering of jurors, actors and filmmakers who are up and about, but nothing really gets going until a little bit later when people start returning from the first batches of daily screenings at Abu Dhabi Theatre and Marina Mall and the doors to the daily seminars are open.

For now, people chat quietly in the bright open space, relaxing into white leather sofas indoors or sweating in the humid heat for the sake of a cigarette outside.

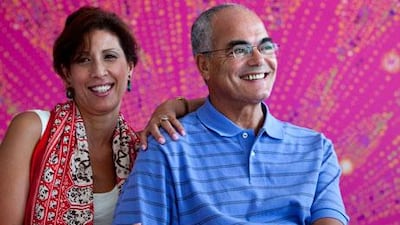

Ahmed El Maanouni is the image of a man at ease as he sits drinking tea with Badria, his producer wife.

"But I am alert all the time. Everything I see, everything I hear, is feeding my inspiration as a filmmaker," he says. This, then, is work for El Maanouni. "Oh yes," he smiles. "Because filmmaking is not like any other business or any other job. It's like a philosophy of life or a religion and it's something you practice all the time."

Four months ago El Maanouni received the telephone call from Scarlet, asking him to be president of the Emirates Film Competition jury. The category encompasses both established and new directors from the UAE and GCC countries.

It is more than 30 years since El Maanouni made his own debut with Oh The Days! (Al Yam! Al Yam!). It was the first Moroccan film to be screened at Cannes in 1978 and was shown again at this year's ADFF. El Maanouni is well aware of just how important a festival's recognition can be to a young filmmaker. "It is a responsibility I feel very deeply. I did not hesitate to accept the invitation to be president of this jury, it is exciting, but it is not something you should take lightly."

Much of El Maanouni's time is mapped out according to the films he and the jury must see. He has been on many judging panels in his time but this festival experience is rare, he says, in that the jury watch the films along with the audience rather than at private screenings. "I like this," he says. "We are a very obedient group. We take our schedule and we see the films we are told to and we take notes all the time. But films are made to be seen with an audience, after all, and the reception of the audience adds something to the experience. It doesn't fundamentally change a view or judgement but it adds a pleasure."

After the screening he and the five other jury members sit and chat over coffee before his thoughts turn to what other screenings he can cram into the day. "I try to see at least a couple," he says. "But my schedule is often clashing."

When we first meet there are still several competition films to be seen, so the real jury deliberations have yet to begin. It is all very easygoing, El Maanouni, says. After so many years in the business he and Badria are relishing the opportunity to spend time with old friends, watch films, talk films and hear about new projects. He says the film community is divided not so much into tribes as into "aesthetic families".

El Maanouni's daily routine is structured - an early morning work out at the gym, fruit for breakfast and then a few hours reading about the films he will see that day. If the festival hasn't provided enough information on an individual movie then he will ask for more.

"I am very conscious that I am not looking for virtuosity or technical expertise because these are films coming from makers who are just growing, just beginning. I am looking for that flare that will illuminate a whole field. I am looking for that personal tone that comes through, that filmmaker who has something to express, a story to tell."

By the following day the deliberations have begun in earnest. We meet late in the afternoon. El Maanouni is wearing a different shirt but the same smile. He is surprised, he admits, by some of the discussions he and his fellow jurors have been having. They meet in a secret room, he says, relishing the mystery of it, and their talks are fuelled by gallons of tea and coffee. What he had not expected, he says, was the agreement that has become clear in the jurors' reactions to the films. The four other members are Abdullah Al Eyaf, a prominent Saudi filmmaker, Maysoon Pachachi, a London-based filmmaker of Iraqi birth, Khadija Al Salami, Yemen's first female filmmaker and Hani Al Shaibani, a Dubai-born filmmaker. El Maanouni says, "We are five very different people and yet this shows how film works and how it can touch you."

But there is a lot still to consider, he notes. The winners will be announced within a matter of hours, so there is little time left for the judges to make their minds up. And however positive the deliberations, it is not, one senses, a decision that will be easily taken.

"You hope you are not going to misjudge," El Maanouni admits. "You hope you are not going to miss some great talent. But I believe that talent imposes itself - however fragile its state."

As for the process of judging it is, El Maanouni says with some charm, "like falling in love. You are ready to fall in love. This is how it must be. When I enter the cinema I open myself and am absolutely ready."

***

Lamia Chraibi is apologising for any lapses in her frankly impeccable English. Mid-afternoon on day five of the festival and, so far, it has been all work and all play for the Moroccan producer recently named among Variety Arabia's "Five Producers to Watch." Chraibi has a film showing this year, director Hisham Lasri's, The End, as well as a project in development for which she has received Sanad funding from the film festival. Each year the organisation awards grants to selected filmmakers from the Arab world and connects them with industry professionals who can either help them realise their projects or ensure completed films reach an audience.

She hasn't had more than three and a half hours sleep a night since she flew in from Casablanca on the festival's opening day. She is exhausted. And she is exhilarated - surrounded by friends, peers and people who, she feels quite certain, could turn projects that are currently just pipe-dreams into big-screen reality.

She says, "I am here with my director, Hisham, and a couple of actors from my film. In the last five days we have done so many things, met so many people. Sanad has proved really a wonderful thing for me because they have designed a programme specifically for me and for my project. It is both a fund and an organisation [that] puts you in touch with industry people.

"Filmmaking is not just about meeting people with funds, it's about meeting the right people for your project with funds and creativity. There are hundreds, thousands of filmmakers with projects looking for funding and creative input. How am I to stand out from the thousands? How am I to be heard? That is where Sanad comes in and puts me forward, gives me that legitimacy over and above the work I have already done. For me it is really perfect this year because I have a project to talk about and a film that I can point people towards and they can see."

The meetings began almost as soon as Chraibi and her team arrived early on the morning of the 12th, with her Sanad schedule in one hand and 23-page film treatment in the other. One particularly fruitful meeting, she reflects, was with Isabelle Fauvel, founder of Initiative Film, a consultancy based in Paris and providing assistance with film development. They discussed the film treatment that won Chraibi funding when she submitted it earlier in the year and already, she says, she has started to make changes to the concept.

"Everything here," Chraibi says, casting around the lounge, gesturing beyond, "everything in this festival is condensed. People that it might take me weeks, months to contact, far less meet, are here to bump into, to talk to, have a coffee with. That is what is so important about here. It is not so much that deals are signed but that you make those contacts and that your project and your face is at the front of their mind. So when they go back to wherever and they have all these other treatments put before them, it is my face they remember and my treatment that stands out."

It is all very different from the majority of Chraibi's year spent in her office in downtown Casablanca. "It is very industrial," she says. "There is no glamour outside my office. All the glamour happens inside it." Much of her work is a solitary process - seeking out investors and seeking out projects that excite her. At the moment she has five or six such projects on the go; feature films in the development stage funded into existence, for the most part, by the television work that is her production company's bread and butter.

She travels a lot to France to see films and meet with financiers. Her energy and her enthusiasm is boundless. Even with this week's dense schedule, she explains, she is squeezing in as many screenings as possible.

"During my breakfast I'm organising my day and working out what movies I can see between meetings. I have managed to see a couple a day so far. This is why I like festivals so much. I really love the social part, too."

At the end of each day there is always a dinner to go to and a party where work melts seamlessly into play. "Very often," she says, "We stay until we are kicked out and then we carry on talking somewhere else until it is light."

She checks her watch and finishes her tea. She has a meeting with her director and is already a little late. "I have been to Cannes, to Berlin and to Belgium, but this is the one I am enjoying the most so far. I have achieved more in five days than I could in five months from my little office in Morocco."

¿¿¿

It is an odd picture. At one end of this eighth-floor corridor of the Fairmont Bab Al Bahr, seven bodyguards stand in front of a door to a room that nobody is the slightest bit interested in entering. At the other the assembled press, a film crew from Lebanon, a magazine journalist and her photographer armed with an embarrassment of lights and cameras wait outside a room we have just been told is empty. The Lebanese presenter slumps to the floor. Khaled Abol Naga is running late. An hour after his hour with the press was due to begin he is still, "on his way." And it is the ADFF talent host, George Saad, who will have to work out how to steal just enough minutes from the rest of Abol Naga's schedule to appease both the Egyptian star and everyone who wants a bit of him. It is a delicate sort of balance to strike and one which Saad, a freelance assistant director by trade, seems to be very good at managing.

From the moment Abol Naga flew in from Cairo to the moment he leaves at the end of ADFF, Saad is his assistant, the keeper of his diary and a polite but firm wall between press and the star if necessary. He is constantly fielding phone calls, emails and instant messages and continually reworking Abol Naga's schedule - a schedule carefully crafted in a calm pre-festival reality that bears no relation to the 10-day circus itself.

"There is nothing glamorous about my job," Saad admits. "It's a lot of work, a lot of running around and a lot of reorganising things that you've just organised."

Saad clutches a white folder. "This," he says solemnly, "is the schedule." He leafs through each page, day by day information, timings, where Abol Naga must be and when, when he must start getting ready for his many red carpet appearances; when a car must be requested; when he must be in hair and make-up for a shoot; when he must eat ... on and on it goes. Saad snaps it shut, pats a rather tatty notebook, filled with scribbles and names and telephone numbers and times. "But this," he says, "is the Bible." Very little, it transpires, runs strictly to schedule, but when so much is done on the hoof there isn't time to reprint its pages: it remains an untouched archive of a plan that was always optimistic at best.

Saad's phone rings. "He's on his way," he says, and suddenly Abol Naga is striding down the dimly lit corridor towards the clutter of waiting press. He looks more tired than he did when we met the previous day.

Then, it was early afternoon and he was preparing to take his place on a panel of Arab filmmakers to discuss the impact of the Arab Spring on filmmaking. It was a less than successful discussion. Abol Naga, who spent several days with protesters in Tahrir Square, later admits that he had tried to persuade the organisers to set aside two hours rather than one for this seminar. "Because you have to talk about the politics of it before you can move onto the film, but by the time you have covered that," he says, "the time is gone." It is true that, though proceedings ran into overtime, it seemed that the topic of filmmaking had barely been touched.

This is a strange festival for Abol Naga. He is an award-winning actor and filmmaker for films such as Heliopolis, One-Zero and Microphone. Wherever he goes there is the predictable frisson that shimmers around most stars; the hushed recognition from fellow hotel guests, the squeals of excitement from fans, the glad-handing and greetings from other filmmakers, other stars. But he is not here promoting a film so much as his production company and an idea - something he refers to as the revolution in filmmaking.

"I started my career as an actor in 2000 but my background is engineering. It is not a science but the art of applying science, so I've always been interested in the many facets of film. Now I'm producing, I've started writing with a group of people and I'll be directing next year. I started a distribution company which is based in Paris and I am part of Team-Cairo, an independent pool of filmmakers who are sharing resources, writers, directors even cameras. This is the new revolution in filmmaking because there is a whole new generation, the first wave of Arab filmmakers who are reflecting what is going on across their region. So I'm here with many hats on."

A couple of days ago he was handing an award to Lily Cole at the premiere of The Moth Diaries. Yesterday he was calling for the audience at the Arab Spring seminar to stand for a minute's silence to remember all who have fallen in the uprisings. Now he is debating with Saad if he really must do a photoshoot for a particular magazine. "Can't we do it tomorrow?" he asks. "It is so late, the light will be gone anyway." "No," Saad explains, "this is their last day. It will only take 10 minutes." But, even as Abol Naga agrees, he rolls his eyes in a wry acknowledgement that nothing "only takes 10 minutes," ever.

He takes a swig from a can of Red Bull. It is after 5pm but he hasn't had a chance to eat. Saad runs through the rest of the day's schedule. Several interviews, a couple of shoots and a meeting, then the red carpet at 9pm with an optimistically scheduled 8pm deadline for being ready.

"Every day is different. But every day is busy," Abol Naga smiles. "You have limited time, you want to do as much as you can, see as many films, see as many people as you can. And when you are with a family of likeminded filmmakers the fun is more intense. You go to a party, you skip the small talk. Even with people you don't know you know them by their work and it's fantastic.

"I think ADFF really is a smart festival. It is changing and learning all the time. It changed its name. It started with a lot of bling and red carpet focus but realised it was better to focus more on local talent and Arab films. So it's changing all the time and reflecting the world, which is what film should do."

By now, Saad is pointing at his watch, "One minute," he mouths. A film crew is jostling to set up. For a moment Abol Naga fixes me with an intense look, "This is not a typical year or a typical festival for me. This year is very special because this year I could have not been here. I could have been dead.

"That thought is with me all the time. The red carpet feels completely different to me now. I see it and I see the image of blood on the streets. It haunts me. It's here in this room right now."

Saad's phone rings again and our time is up.

Laura Collins is a senior features writer at The National.