The legacy of TE Lawrence, the British intelligence officer who fought alongside Arab irregulars and was immortalised in David Lean's film, varies markedly between the West and the Middle East. Alasdair Soussi looks at the man and myth, 75 years after his death.

The arrival of the British-led Imperial Camel Corps into the Arab camp at Aqaba was always likely to cause friction. Despite fighting as allies against the might of the Ottoman Empire in the 1916-18 Arab campaign to drive the Turks out of the Middle East, the British troopers and the Arab irregulars never made comfortable bedfellows.

This particular summer's day in 1918, at the closing stages of the Great War, was to be no different. The army encampment, in what is today Jordan's southernmost city, reverberated to the sound of excited cries and musket fire as the 314-strong imperial troops galloped into town.

Such was the greeting afforded them by the Arabs that many in the Camel Corps thought Aqaba itself was under attack. By nightfall, tensions had reached breaking point.

Unfamiliar with the ways of the Arab camp and convinced they had been shot at while bathing in the sea earlier that day, several troopers were about to take matters into their own hands with the aid of a few grenades when a figure in white appeared.

"He stood in the middle of the square, flung back his aba, showing his white undergarment, and illuminated by the countless fires, raised his hand," one soldier recalled.

"Immediately the firing ceased, the hubbub died down and we had a peaceful night." That figure was Thomas Edward Lawrence.

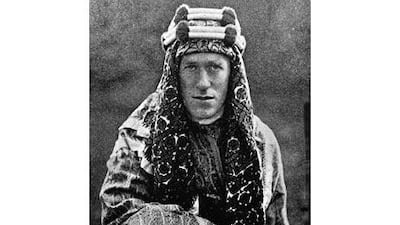

Lawrence of Arabia

TE Lawrence, who died 75 years ago this week, and who was pivotal in the success of the Arab revolt against the Turks, was the man the world would come to know as Lawrence of Arabia, and that anecdote - almost mythical in tone, yet a documented fact - is one of hundreds that have surrounded a life that continues to provoke the debate.

David Lean's 1962 epic, starring Peter O'Toole, was based on Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence's memoir of the two-year campaign. The film was a global sensation, but it was not the first time that the Lawrence myth had captured the popular imagination.

Forty-three years earlier, Lowell Thomas, a US journalist, toured the world with a highly romanticised film about Lawrence shot in the desert towards the end of the war.

With Allenby In Palestine And Lawrence In Arabia was an immediate hit, not least in Great Britain where Lawrence was born in 1888. Consequently, Lawrence's role in the Arab uprising, his pursuit of victory against the Ottomans, and his complete immersion in the Arab way of life as a British intelligence officer, all contrived to create a man more otherworldly than simply flesh and bone.

Michael Asher, the English-born explorer and Arabist, and author of Lawrence: The Uncrowned King Of Arabia, is one of many who readily subscribes to this view.

"When I went to Lawrence's cottage - now a museum - at Clouds Hill in Dorset [south-west England], it felt like a church. I realised that he was seen in Britain as a secular saint.

If you think about it, Lawrence was really the only 'hero' to emerge from the First World War, a war in which millions died - he was the man who seemed to resurrect in his person the lost dead boys of a whole generation."

Here, in the Middle East, the arena in which Lawrence gained his reputation, there are no such memorials. So what is his legacy in this part of the world?

Like many things concerning Lawrence, the answer is far from simple. At only 1.65m tall and with a head that looked too big for his body, this shy Welsh-born son of an Anglo-Irish father and a Scottish mother was an unremarkable-looking man.

Yet, he possessed a mind that was quite brilliant. After gaining a first-class degree in modern history from Jesus College, Oxford, Lawrence became an archaeologist, and travelled across the Middle East honing his knowledge of its geography and language, both of which he would come to master.

At the outbreak of the First World War, he joined the British intelligence service in Cairo and soon became involved in negotiations to orchestrate an Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire, which was sealed when Britain all but promised the Arabs a single unified nation should they triumph.

But, while the revolt would be a major success, the European powers went back on their word. The Sykes-Picot Agreement, a secret pact cooked up by Britain and France in 1916, carved up the Middle East into colonial spheres of influence in a post-Ottoman world, a betrayal that put paid to any Arab hopes of freedom.

Conflict of loyalty

Lawrence, who fought alongside the Arabs, felt a conflict of loyalty over the actions of the country he was serving. He viewed it as an act of treachery of which he was unwittingly a part. He tried to undermine the Anglo-French agreement both during the war and afterwards, but ultimately failed.

Yet, according to the Syrian historian Sami Moubayed, Lawrence's affection for the Arabs, and theirs for him, was immediate and genuine.

"In all the literature that was written about Lawrence in the Arab world from 1916, the start of the Arab revolt, all the way until 1948, they were very, very positive about him," says Moubayed, who is editor of the Syrian publication, Forward Magazine.

"They viewed him as an Orientalist who had a lot of passion for the Arab world and who wanted to see the Arabs free and emancipated. That was the first phase of literature."

The second phase, says Moubayed, came into being with the creation of the State of Israel in 1948.

"The views about the man changed after the Arab-Israeli war of 1948, when many in the Arab world began to look upon Britain with a lot of scepticism and in a very negative manner - particularly from historians, journalists and writers."

The British government had, after all, with its Balfour Declaration, supported a Jewish state in Palestine since 1917. Today among the intellectual classes of the Arab world, there is, says Moubayed, almost an "equal balance in how to deal with Lawrence.

"Many Arabs still see him as a phenomenon, while others see him as nothing but a British officer who, at the end of the day, was working to advance his own and his country's national interest. But there is a feeling in the Middle East, developed over the past couple of years, that the image of Lawrence has been inflated by so much propaganda, photos of him wearing traditional Arab garb, and, of course, the movie that was produced about the man."

Perhaps the most intriguing of all is the view of the general Arab public. This, says Moubayed, was demonstrated a couple of years ago when a made-for-TV series on Lawrence was broadcast, starring the popular Syrian actor Jihad Saad.

"It was a 30-episode series about Lawrence and his adventures in Arabia, screened during the month of Ramadan, and it was a major flop because the Arab public were no longer interested in visiting that history. I think it speaks volumes about the man and how he is perceived nowadays in the Arab world."

Such sentiments are echoed by the British historian James Barr, author of Setting The Desert On Fire: TE Lawrence And Britain's Secret War In Arabia, 1916-18.

"The place where I noticed Lawrence resonated the most was in Wadi Rum in Jordan," says Barr. Lawrence based his operations there during the Arab Revolt and made a famous three-day dash to Mudawarra on a racing camel to cut the Hejaz railway line.

"But, even there, most of the Arabs I met weren't too fussed either way," he continues. "They neither thought he was a great guy, nor somebody who had betrayed them horribly. But they did remember the film, because that generated a lot of employment in the 1960s. One man I met told me that his grandfather, who had ridden into Aqaba with Lawrence, was hired as an adviser, and many others had been used as extras."

Michael Asher, who made the TV documentary In Search Of Lawrence, had a similar experience.

"Most Arabs I talked to thought that Lawrence's reputation had been exaggerated. Some said he was just a dynamite man brought in to blow up the railway. I spent a lot of time in Wadi Rum with the Howaytat tribe. Their grandfathers had fought beside Lawrence, but they didn't know anything about him. In fact, when you talked about Lawrence they thought you meant Peter O'Toole, who portrayed him in the film. There was even a place called Lawrence's Well that was dug specially for the film and had nothing to do with the "real" Lawrence. Odd how myths get tangled up. But, I later found out from a female Howaytat bard, or tribal poet, that there were some poems and songs about the original Lawrence."

'Valentino of the desert'

If there is indifference in the Arab world, the same cannot be said of the West. In Britain, Lawrence is seen as a national hero. Yet there is more to him than the Valentino of the desert. For many military theorists, Lawrence was a guerrilla fighter par excellence.

"We might be a vapour," wrote Lawrence in Seven Pillars Of Wisdom, referring to the mercurial military tactic that would give him and his Arab irregulars victory over the Turks. "Lawrence had an epiphany about guerrilla warfare," says Asher, who was formerly a member of the British Parachute Regiment and the Territorial Special Air Sevice (SAS).

"He realised that though the Turks held the railway, they didn't control the country. They were actually boxed in in their garrisons, dependent on the railway. On the other hand, the Arabs, mounted on fast camels, had the run of the whole desert. They were highly mobile. They could hit the railway at its vulnerable points and disappear back into the desert before the Turks knew what was happening.

His ideas were incredibly influential. The British Special Forces idea was founded on them, beginning with the SAS in 1941. The SAS idea came straight from Lawrence - drop by parachute behind enemy lines, make a base there, and sally forth hitting the enemy at his most vulnerable points, vanish back into the wilds where he can't follow.

Today, Lawrence, whose close friend and fellow Oxford graduate Gertrude Bell would be charged with drawing-up Iraq's boundaries in 1921, has found a modern role as part of the American tactics in Iraq and Afghanistan. For example, US general David Petraeus recently devised a counter-insurgency doctrine, drawing on the writings of Lawrence. At the US Army Command and General Staff College in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Lawrence is even on the syllabus.

"We use Lawrence probably not quite in the way that many people expect," says Peter J Schifferle, the director of the college's advanced operational art studies programme.

"The thing I find of use in Seven Pillars Of Wisdom is the part where Lawrence analyses the nature of the inhabitants of the Arabian peninsula, the nature of the Turkish presence as occupying forces, the aspects of the Arab culture and Arab personality. And our intention, at least in its relevance to Iraq and Afghanistan, is to teach students that human beings can do a decent job of thinking through the complexities of a situation."

Some historians are more dubious about Lawrence's relevance.

"Since 2003 with the invasion of Iraq, any number of US army officers have been saying they've read Seven Pillars Of Wisdom," says Barr. "But my reading of it is that it's the story of how very hard it is to win a guerrilla war if you're a conventional army because guerrillas can flit around like a gas. It's difficult to see whether you can get an optimistic message from reading him."

At the Paris Peace Conference at Versailles in 1919, Lawrence tried and failed to persuade the imperial powers to reconsider their designs on the Middle East in the shape of the Sykes-Picot Agreement - a pact that has been widely blamed for the Middle East's subsequent travails.

Two years later he was coaxed back into public service by the then Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill, who appointed him to a special post in the Colonial Office. He was closely involved in the decision to separate Trans-Jordan from coastal Palestine, and in the accession of Prince Faisal, his comrade in the Arab uprising, to the throne of Iraq.

Lawrence died a disconsolate figure in a motorcycle accident in England in May 1935, his light having long since faded.

"I'm a fraud as regards? the Middle East," he wrote five years before his death. In spite of that, Lawrence can be assured of one thing, says Moubayed.

"Sykes, Picot and Balfour are three damned figures in the history of the Arab region. Lawrence is not like that. He shouldn't carry the burden for things he was not responsible for."

Gertrude Bell

The legend of TE Lawrence may live on, but it was a British woman, Gertrude Bell, who was instrumental in the creation of modern Iraq.

Gertrude Bell was born into a family of wealthy ironmasters in 1868 in north-east England. She had a privileged upbringing - her grandfather, Sir Isaac Lowthian Bell, was a fellow of the Royal Society and a founder of the Royal Institute of Chemistry - and in 1886 she went to Oxford University, becoming the first woman to graduate with a first-class degree in modern history.

A slightly built redhead, Bell soon thrust herself into the mysterious and dangerous surroundings of the Middle East, visiting and falling in love with Persia (now Iran) and Mesopotamia (now Iraq) where she learned Arabic.

By 1914, this resilient woman, who would make her name as a spy, mountaineer and photographer, among other disciplines, had covered 25,000 miles of the Middle East, much of it on camel and horseback.

She first encountered TE Lawrence in 1911, while working as an archaeologist. At the time Lawrence was excavating a site at Carchemish, on the Turkish-Syrian border. He described Bell, 20 years his senior, as "pleasant? not beautiful, (except with a veil on, perhaps)."

Bell, by then an expert on the Middle East, pronounced him, rather insightfully, "an interesting boy, he is going to make a traveller".

"They then briefly worked in Cairo for British intelligence during 1915-16," says James Barr, the British historian.

"There is no doubt they got on well there, though one suspects that Bell, the only female political officer in the Middle East, was relieved to see familiar faces. Soon after arriving, she described how she regularly had lunch with the 'exceedingly intelligent' Lawrence and David Hogarth, the Oxford don who was their mutual friend.

"It's too strong to say they were close friends. Lawrence only wrote to her once after that, in 1923, before she died in 1926."

The pair disagreed on British policy in post-First World War Iraq, but worked together under Winston Churchill at the 1921 Cairo Conference to settle the country's future. Bell was an integral part of the administration of Iraq, advising the new King Faisal and supervising the selection of appointees for government posts.

Working with the new king was not easy: "You may rely upon one thing - I'll never engage in creating kings again; it's too great a strain," she said.

Bell overdosed on sleeping pills, either by accident or by design, in Baghdad.

On hearing of her death, Lawrence wrote: "That Irak [sic] state is a fine monument; even if it only lasts a few more years, as I often fear and sometimes hope. It seems such a very doubtful benefit - government - to give a people who have long done without." Bell is buried in Baghdad.